Mandarin Chinese has a reputation for being a very difficult language to learn. Chinese as a language is radically different than Western languages like English, Spanish, and German, which share a common ancestry and uses the same alphabet.

So, if you want to learn Chinese quickly and effectively, you’d need to have the right determination and must be willing to spend a significant amount of time on intensive training.

However, learning Chinese is not impossible, and these facts shouldn’t discourage you from learning one of the most popular languages in the world. Remember that millions of people have learned the language in the past few years, and certainly, you can, too.

Here, we will discuss some of the most common challenges in learning Chinese, what we should expect from them, and most importantly, how we should tackle the issue.

Let us begin.

Challenges in Learning Mandarin Chinese

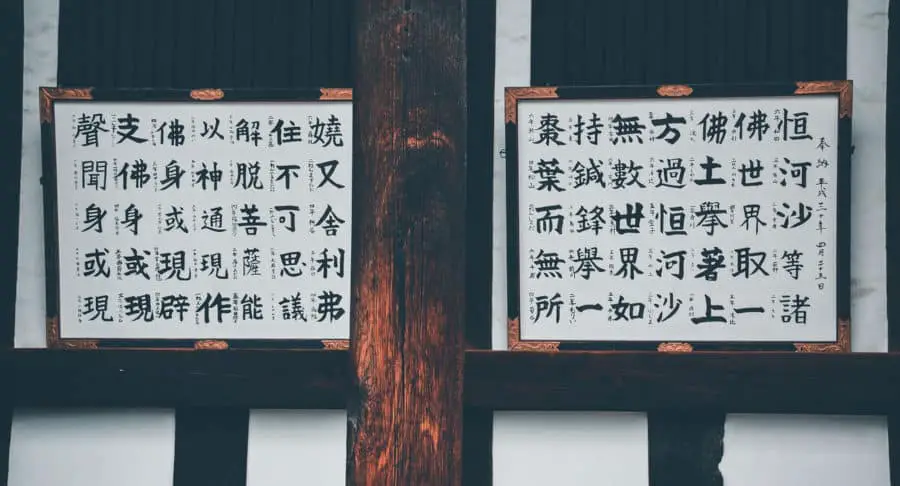

1.The Complex Chinese Characters

When learning English, Spanish, or other alphabet-based languages, the studying begins with the letters. The English alphabet has 26 letters, and the alphabet system is shared with various Western languages.

Even in languages like Russian or Greek that use different alphabets, we’d only need to memorize between 20 to 30 letters in most cases.

There are, however, more than 50,000 characters in Chinese, and an educated person in China is expected to know around 8,000 of these characters. Even in a very intensive training environment, it’s going to take years of daily memorization before we can memorize these essential 8,000 or so letters. This is arguably the biggest challenge in learning Chinese as a language.

The Chinese pictogram system, however, does have its advantage: the characters stay the same although people’s pronunciation evolves through time. Compare this to how old English is so different than the spelling of modern English.

Another advantage of the Chinese characters is that the letters stay the same for different dialects. Hong Kong, for example, uses Cantonese instead of Mandarin but uses the same Chinese text.

To summarize:

- You’d need to memorize at least a few thousands of Chinese characters before you can effectively communicate with the language (especially written communication)

- You’d also need to learn two versions (simplified and traditional) of some characters, increasing the difficulty

- There are a lot of characters with more than one meaning/definition. Chinese characters were initially developed for a single meaning or concept, but some of them developed more connotations and sometimes can be totally unrelated to the original meaning

- Each of these characters can have more than one pronunciation, each might have totally different meaning. We will discuss more of this below.

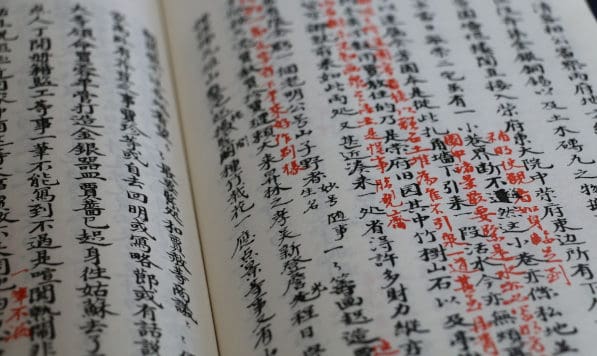

Unfortunately, there is no shortcut to this challenge. Many people have tried to develop techniques and methods to help us memorize Chinese letters, but spaced repetition (the technique to memorize a certain fact with time intervals increasing each time the fact is presented) is still the only effective one. Also, spaced repetition won’t speed the process, it just helps the memorization to stick better.

Related reading: How Old is the Chinese Language? – A Brief History from Archaic to Mandarin – Opens in new tab

2. Complex Tonal Rules

Chinese is a tonal language. Meaning, a difference in intonation, and even a slight mistake can produce a very different meaning.

The Chinese language involves four common tones and three basic tonal rules:

- First tone: The first tone is high and level, and it’s important for the speaker to keep the voice even and monotone across the whole syllable. In pinyin, represented with a straight horizontal line above a letter (like “ā”) or as number “1” written after the syllable. For example, “mā”

- Second tone: Rises moderately, similar to how we ask a question in English. Represented by a rising diagonal line above the letter in pinyin (“á”) or as number “2” written after the syllable. For example, “má”

- Third tone: falls and then rises again, and so in pinyin is represented by a curved line above the letter (“ǎ”) or as a number “3” after the syllable. For example, “mǎ”

- Fourth tone: starts high then drops sharply, similar to how we shout a command in English. Represented by a dropping diagonal line (“à”) or as number “4” written after the syllable. For example, “mà”

There’s also the neutral (flat) tone which is unmarked in pinyin, but is sometimes marked with a “0” or “5”.

Related reading: “How To Travel in China Without Speaking Chinese?“

There are also three basic rules to follow:

- 不 (bu): When the word 不 (bù) precedes the fourth tone, it automatically changes to second tone (so, “bú”). This might not be reflected in the written pinyin

- 3-3 to 2-3: When there are two third tones in a row, the first one must be changed into the second tone. This rule should be followed even when it’s not reflected in the written pinyin.

- 一 (yī): The character 一 (yī) representing the number “one” is always the first tone when alone, the second tone when followed by a character with a fourth tone, and fourth tone when followed by other tones.

So, how can we overcome this challenge? Again, unfortunately, there’s no shortcut, and you should listen to Chinese conversations as often as possible.

In fact, you should start studying Chinese by focusing on listening and reading whatever you are listening to. As time goes, you will get used to the sounds and make a habit of these tonal differences and rules.

3. Complex Language Variations

The Chinese language has several different dialects and the variations can be very significant. Remember that in China alone, the Chinese language is spoken by more than a billion people spread over a massive geographic location.

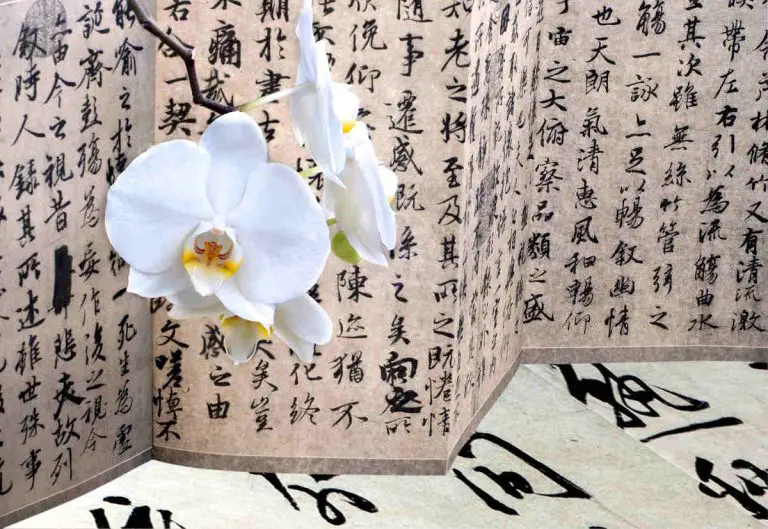

Mandarin is the standard dialect, but there are many variations in China alone, not to mention outside China, like how they use the Cantonese dialect in Hong Kong. Also, there can be very significant differences between formal and casual conversations. In Chinese literature, there is also classical Chinese (which can be treated as a language of its own) which is often interwoven into modern Chinese literature and even films.

So, when learning Chinese, these variations and differences might confuse you.

Most Chinese learners learn Mandarin Chinese, or 普通话 (pǔ tōng huà), translated to “common language”. If you live or travel to Beijing, for example, this is indeed the common language in the area. However, if you go to Shanghai, the local language is the Shanghainese dialect, not Mandarin. Many cities, towns, and even small villages in China have their own dialects.

Here are some important dialects that are spoken in China you should know:

- As mentioned, pǔ tōng huà or common Mandarin can be heard all over China as the official dialect. However, it is more common in northern parts of China including Beijing.

- The Hakka dialect or Kejia is the language of Hakka people, who are spread out across Guangdong, Jiangxi, Guizhou, and Taiwan, among other locations.

- The Gan dialect can be heard in western parts of China, spoken particularly in and surrounding Jiangxi province

- The Wu dialect, also famous as Shanghainese language, can be heard around Shanghai and the Yangtze Delta

- The Min dialect is spoken in Fujian and southern China

- The Xiang is a southern dialect, especially in Hunan province

- The Yue dialect or Cantonese is spoken in Hong Kong and Macau, as well as in Guangdong and Guangxi

A possible solution if you are traveling to locations with dialects you don’t know is to write things down. As mentioned, the Chinese writing system is always the same across all dialects. Even when you can’t talk to each other, you can always write.

Related reading: Chinese as A Second Language – Is Learning Chinese Worth It?– Opens in new tab

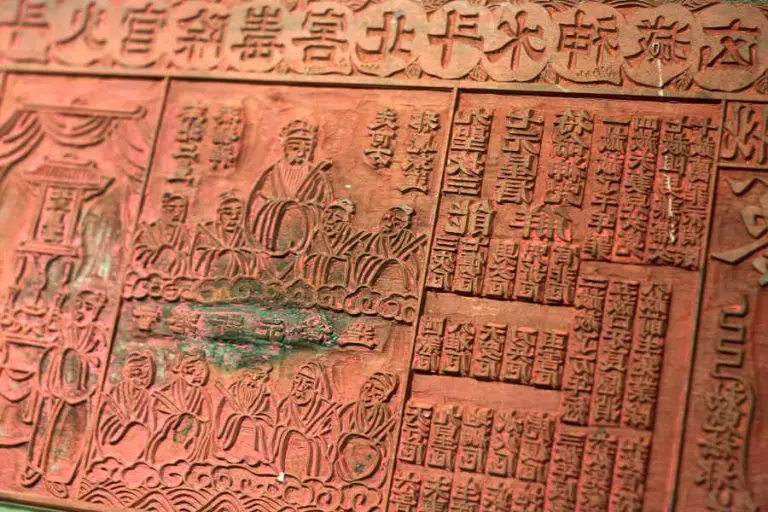

4. Chinese Writing System is Very Complex

The complexity of the Chinese writing system is not only about the number of characters.

For instance, it can be very difficult to properly pronounce a Chinese word by just looking at the character, while we can easily guess the spelling of a language we don’t know but written in the common alphabet just by looking at it. On the other hand, you can repeat and memorize a Chinese word as many as you can and you might still get zero ideas to how the word should be written.

However, although the Chinese writing system might not be very obvious, there are several advantages of the Chinese writing system:

- Consistent word order

There are languages where the meaning of the phrases can change depending on the word order. But with Chinese, the order is always: time-subject-verb-object-particle. And we can change the tense of a statement with the time indicator at the start of the phrase.

- No tenses

The Chinese language doesn’t involve different tenses, and as mentioned, you can simply state the time period of the event at the beginning of each sentence.

- No verb conjugation

The verb conjugation is when the form of the verb changes depending on the tense, and in some languages, on the subject. In Chinese, the verb is always constant.

End Words

Yes, Chinese is a hard language to learn, and even harder to master. However, that’s not to say that it’s impossible. Many people have been successfully learning Chinese even before this age of online translators and dictionaries. With enough commitment and determination, slowly but surely we can learn the language.

Related reading: The Most Commonly Asked Questions About the Chinese Language – Opens in new tab

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image by Evelyn Chai from Pixabay