Chinese inventions have played a pivotal role in shaping the course of human history, contributing significantly to various aspects of global civilization. From the revolutionary Four Great Inventions – papermaking, printing, gunpowder, and the compass – to a myriad of other creations, Chinese inventions reflects the ingenuity, creativity, and resourcefulness of the Chinese people throughout the ages.

These innovations transcended borders, influencing cultures and propelling advancements across the globe. From the way we navigate the seas to the knowledge we record on paper, the echoes of Chinese inventions resonate in our daily lives.

In this article, we will explore a chronological list of some of the most remarkable Chinese inventions that have influenced the world as we know it today.

Ancient Chinese Inventions (Pre-1000 BCE)

Silk production techniques

Silk holds a special place in the history of China, representing both luxury and innovation. The development of silk production techniques dates back to around 2700 BCE during the Neolithic period in China. Legend has it that Empress Leizu discovered silk when a cocoon fell into her tea, unraveling its fine threads. This marked the beginning of sericulture, the cultivation of silkworms for silk production.

Over the centuries, Chinese artisans perfected the art of silk production, devising methods to rear silkworms, harvest their cocoons, and extract the delicate threads. These techniques were closely guarded secrets, and the export of silkworm eggs or mulberry seeds was strictly prohibited, ensuring China’s monopoly on silk production for centuries.

The Silk Road, established during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), facilitated the exchange of silk and other goods between China and the West, further cementing silk’s significance in global trade and diplomacy.

The development of silk production techniques not only revolutionized the textile industry but also played a vital role in cultural exchange, influencing fashion, art, and diplomacy across continents.

“Silk has long been considered one of China’s greatest inventions, a product that not only changed the course of history but also greatly impacted the world.”

— Li Hong, Chinese Historian

Chinese Lacquerware

Chinese lacquerware represents a sophisticated art form that dates back over 7,000 years. Lacquer, a natural resin derived from the sap of the lacquer tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), was initially used for its protective and decorative properties in China.

The earliest evidence of Chinese lacquerware dates back to the Neolithic period, with archaeological discoveries revealing intricately decorated objects coated in layers of lacquer. These early artifacts showcased the Chinese artisans’ mastery in applying lacquer to various materials such as wood, bamboo, and metal.

During the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) and subsequent periods, lacquerware production flourished, with artisans developing advanced techniques for carving, painting, and inlaying to create exquisite pieces. Lacquerware became highly prized luxury items, used by the nobility for ritual, ceremonial, and decorative purposes.

One notable innovation in Chinese lacquerware was the use of “carved lacquer” technique during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). Artisans would meticulously carve intricate designs into multiple layers of lacquer, creating a three-dimensional effect that was both visually stunning and durable.

Chinese lacquerware gained international renown through trade along the Silk Road, influencing artistic traditions in neighboring countries and beyond. The unique aesthetic and craftsmanship of Chinese lacquerware continue to inspire artists and collectors worldwide, preserving its legacy as a quintessential Chinese invention. (Further reading: Chinese Lacquerware Techniques and History)

“Chinese lacquerware represents the pinnacle of craftsmanship and artistry, with its exquisite designs and durable finish captivating audiences for centuries.”

— Zhang Wei, Art Curator

Warring State period (475 BCE – 221 BCE)

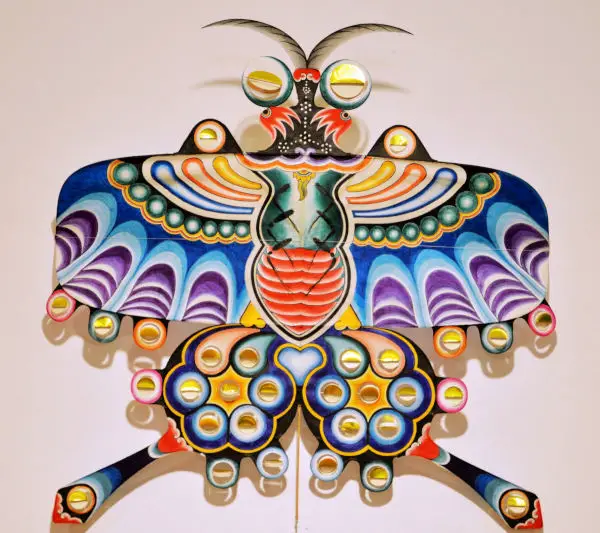

The Kite

The humble kite, a simple yet ingenious invention, holds a special place in Chinese culture and history. While the exact date of invention remains debated, some legends credit the kite to a resourceful farmer who tied a string to his hat to keep it from blowing away. Around the same time, philosophers like Mozi experimented with crafting wooden bird-shaped kites, hinting at the early use of kites beyond simple amusement.

The Han Dynasty saw the use of kites for military purposes. Generals employed them to measure distances during sieges and even experimented with carrying messages or lifting soldiers (though with limited success!).

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), kites became popular as festive decorations and entertainment for both commoners and the imperial court. Skilled artisans crafted kites in elaborate designs, ranging from mythical creatures to geometric patterns, using materials such as silk, bamboo, and paper.

The versatility of kites extended beyond leisure activities, with practical applications such as lifting meteorological instruments for weather forecasting and providing inspiration for early experiments in aviation. Chinese kites also played a role in cultural exchanges along the Silk Road, spreading their popularity to neighboring regions and beyond.

Today, the kite remains an enduring symbol of creativity, freedom, and cultural heritage, celebrated through festivals, competitions, and artistic expressions worldwide. Its evolution from a utilitarian tool to a cherished form of recreation reflects the ingenuity and enduring legacy of Chinese innovation.

Related reading: “Historical and Modern Facts about Chinese Kites” and “Chinese Kites History and Origin“

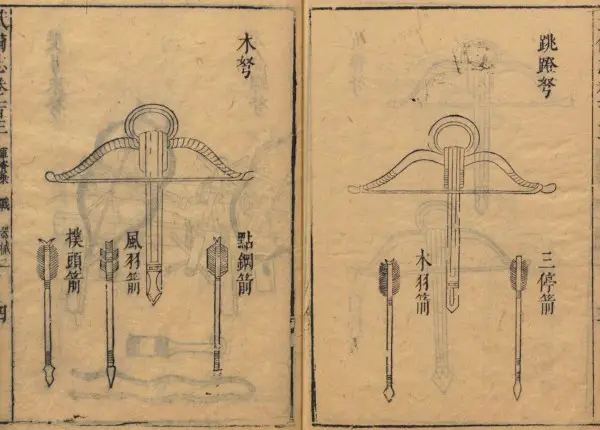

The Crossbow

The crossbow, a formidable weapon that revolutionized warfare, is another remarkable invention with roots in ancient China. Its invention is believed to date back to the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), a time marked by intense military competition and technological innovation.

The crossbow offered distinct advantages over traditional bows, such as greater accuracy, increased range, and ease of use. Its design featured a horizontally mounted bow mechanism, allowing users to release powerful projectiles with minimal effort. This made the crossbow particularly effective for infantry and siege warfare, leveling the playing field against opponents with superior numbers or cavalry.

During the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) and subsequent periods, the crossbow played a pivotal role in the unification of China under the First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang. Its widespread adoption by the imperial army contributed to the empire’s military dominance and expansion.

Chinese crossbow technology continued to advance over the centuries, with improvements in materials, design, and manufacturing techniques. By the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), crossbows had become standard-issue weapons for soldiers across China, further solidifying their importance in warfare.

The crossbow’s impact extended beyond China’s borders, influencing military tactics and strategies in neighboring regions and beyond. Its introduction to Europe during the Middle Ages revolutionized medieval warfare, shaping the course of military history in the Western world.

Despite advancements in firearms technology, the crossbow remained in use for centuries, valued for its reliability and versatility on the battlefield. Today, while no longer a primary military weapon, the crossbow continues to be appreciated for its historical significance and remains a popular tool for hunting, sport, and recreation.

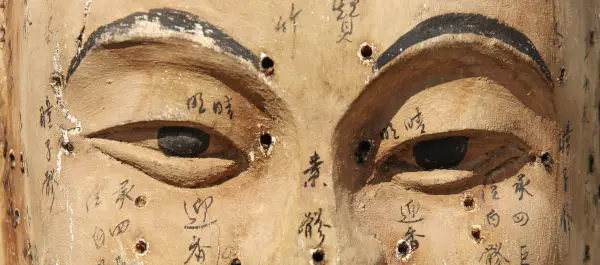

Acupuncture: A holistic approach to health and wellness

Acupuncture, a cornerstone of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), has a history spanning thousands of years and remains a widely practiced therapeutic technique today. Rooted in ancient Chinese philosophy and medical theory, acupuncture involves the insertion of thin needles into specific points on the body to stimulate energy flow and restore balance.

The precise origins of acupuncture are shrouded in legend and archaeological evidence, with early references dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE). Over time, acupuncture evolved from simple stone needles to the fine metal needles used in modern practice.

The theoretical framework of acupuncture is based on the concept of Qi, the vital energy that flows through the body along pathways known as meridians. According to TCM theory, disruptions or imbalances in Qi flow can lead to illness or discomfort. Acupuncture aims to restore harmony by regulating the flow of Qi and promoting the body’s natural healing processes.

Acupuncture gained widespread acceptance and refinement during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), with practitioners documenting their experiences and developing systematic approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Acupuncture techniques diversified over time, incorporating various methods such as moxibustion (the burning of dried herbs) and cupping (the application of suction cups to the skin).

Despite skepticism from some quarters, acupuncture continued to thrive and spread throughout East Asia and beyond, influencing medical practices in neighboring countries such as Japan and Korea. The integration of acupuncture into Western medicine gained momentum in the 20th century, with growing interest in its potential therapeutic benefits for a range of conditions.

Today, acupuncture is recognized as a valuable adjunct therapy for pain management, stress reduction, and various health conditions, with millions of people worldwide seeking its benefits. Its enduring popularity and efficacy underscore its significance as a profound contribution to both traditional medicine and global healthcare.

“Acupuncture, rooted in ancient Chinese medical philosophy, offers a holistic approach to healing and wellness, balancing the body’s energy and promoting health.”

— Dr. Li Xin, Acupuncture Practitioner

Chinese Inventions in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

Porcelain

Porcelain, also known as china, is one of China’s most renowned inventions, with a history spanning over 2,000 years. The origins of porcelain production in China can be traced back to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), although early examples were relatively primitive compared to later developments.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), significant advancements were made in porcelain production techniques, resulting in the creation of high-quality porcelain with a translucent white appearance. This “true” porcelain, known as “qingci” or “blue-green ware,” became highly sought after both domestically and abroad.

The Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) is often considered the golden age of Chinese porcelain, with kilns such as those in Jingdezhen producing exquisite pieces for imperial use and export. Innovations such as underglaze painting, celadon glazing, and the use of cobalt blue for intricate designs further elevated the artistry of Chinese porcelain.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE), porcelain production reached new heights of sophistication, with advancements in kiln technology leading to the creation of large-scale pieces with intricate designs. Ming porcelain, characterized by its vibrant colors and intricate patterns, became highly prized by collectors around the world.

The export of Chinese porcelain along maritime trade routes, such as the Maritime Silk Road, facilitated cultural exchange and established China as a global center for ceramic production. Chinese porcelain continues to be celebrated for its beauty, durability, and technical excellence, representing a timeless legacy of Chinese ingenuity and craftsmanship.

“The development of porcelain during the Tang Dynasty marked a golden age of ceramic artistry in China, producing works of unparalleled beauty and sophistication.”

— Chen Ming, Ceramic Historian

The Compass

The invention of the compass is a landmark achievement in Chinese history, revolutionizing navigation and maritime exploration. Although the exact date of its invention remains uncertain, historical records suggest that the compass was already in use during the Han Dynasty (2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE).

Early Chinese compasses, known as “south-pointing spoons,” consisted of a magnetized lodestone spoon floating in a bowl of water. The spoon would align itself with the Earth’s magnetic field, indicating the direction of south. These primitive compasses were primarily used for geomancy and divination rather than navigation.

The invention of the “dry compass” during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) marked a significant advancement in compass technology. This compass featured a magnetized needle floating on a pivot, enclosed in a protective case marked with directional indicators. It provided a reliable means of determining direction, enabling sailors to navigate accurately even in adverse weather conditions.

Chinese compasses played a crucial role in maritime trade, exploration, and military campaigns, facilitating the expansion of Chinese influence across Asia and beyond. The widespread adoption of the compass in Europe during the Middle Ages further revolutionized global navigation and shaped the course of world history.

The compass remains one of China’s most enduring contributions to human civilization, symbolizing the spirit of innovation and discovery that has defined Chinese culture for millennia.

Paper and its impact on communication

The invention of paper is one of China’s most transformative contributions to human civilization, revolutionizing communication, education, and culture. Dating back to the early 2nd century BCE during the Han Dynasty, the development of paper marked a pivotal moment in the history of information dissemination.

Early Chinese papermaking techniques involved pulping plant fibers, such as mulberry bark, hemp, and bamboo, and then pressing the resulting pulp into thin sheets. This innovation provided a lightweight, durable, and relatively inexpensive alternative to traditional writing materials such as silk, bamboo slips, and animal skins.

The widespread adoption of paper in China led to a proliferation of literature, art, and scholarship, fueling advancements in science, philosophy, and governance. The availability of paper also facilitated bureaucratic record-keeping, taxation, and the spread of religious texts and philosophical treatises.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), Chinese papermaking techniques reached new heights of sophistication, with the establishment of government-run paper mills and the introduction of innovations such as sizing (treating paper with starch or other substances to improve ink absorption) and watermarking (impressing designs or patterns into the paper during production).

Chinese papermaking technology spread gradually along trade routes such as the Silk Road, reaching Central Asia, the Middle East, and eventually Europe. The introduction of paper to the Islamic world during the 8th century CE played a crucial role in the Islamic Golden Age, fostering advancements in science, literature, and the arts.

“The invention of paper during the Han Dynasty was a revolutionary leap forward in communication and literacy, democratizing knowledge and fostering intellectual exchange.”

— Professor Wang Mei, Historian

Seismoscope for earthquake detection

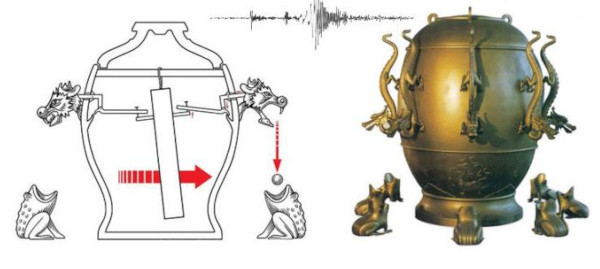

The seismoscope, an ancient Chinese invention, represents an early attempt to detect and measure earthquakes. Developed during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE) by the polymath Zhang Heng, the seismoscope was a sophisticated instrument designed to respond to seismic activity.

Zhang Heng’s seismoscope consisted of a large bronze vessel with eight dragon heads positioned around its perimeter. Each dragon held a ball in its mouth, resting above a frog figurine with an open mouth. When an earthquake occurred, seismic waves triggered a mechanism inside the vessel, causing one of the dragon heads to release its ball, which then fell into the mouth of the corresponding frog.

The direction of the falling ball indicated the direction of the earthquake’s epicenter, providing valuable information for disaster response and early warning systems. Zhang Heng’s seismoscope was celebrated for its ingenuity and accuracy, earning him recognition as one of China’s greatest inventors.

Although Zhang Heng’s original seismoscope was lost to history, contemporary scholars have attempted to reconstruct its design based on historical records and archaeological findings. While the seismoscope was not widely adopted outside of China, its conceptual framework laid the groundwork for future developments in seismology and earthquake monitoring.

The legacy of the seismoscope endures today in modern seismic detection technology, which relies on a network of sensors and instruments to monitor and analyze seismic activity worldwide. Zhang Heng’s pioneering work exemplifies the Chinese tradition of scientific inquiry and technological innovation, contributing to our understanding of the natural world and the pursuit of safety and security.

“Zhang Heng’s seismoscope, an engineering marvel of ancient China, demonstrated the country’s early mastery of scientific observation and technological innovation.”

— Dr. Chen Tao, Seismology Expert

Chinese Fans

Chinese fans have a rich cultural heritage that spans thousands of years, evolving from practical tools to expressions of artistry and elegance. Originating in ancient China, fans were initially used for functional purposes such as keeping cool, shielding from the sun, and signaling status or rank.

The earliest Chinese fans were made of feathers or palm leaves attached to a bamboo frame, with simple designs reflecting their utilitarian nature. Over time, fans became associated with social status and etiquette, with elaborate designs and materials reserved for the nobility and aristocracy.

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), fan-making techniques advanced significantly, leading to the production of intricately carved wooden fans adorned with lacquer, silk, or precious metals. Fans became fashionable accessories, with styles and designs reflecting the tastes and trends of each dynasty.

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) saw the golden age of Chinese fan-making, with artisans experimenting with new materials and techniques to create exquisite folding fans known as “ruyi” or “wish-granting” fans. These fans featured delicate silk or paper panels intricately painted with scenes from nature, poetry, or mythology.

Chinese fans reached new heights of popularity during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), with the widespread use of hand-painted silk fans as gifts, tokens of affection, and diplomatic offerings. The elegant folding fan, known as “shan,” became a symbol of refinement and sophistication in Chinese society.

Click here to see some awesome Chinese Fan designs.– Aff.link

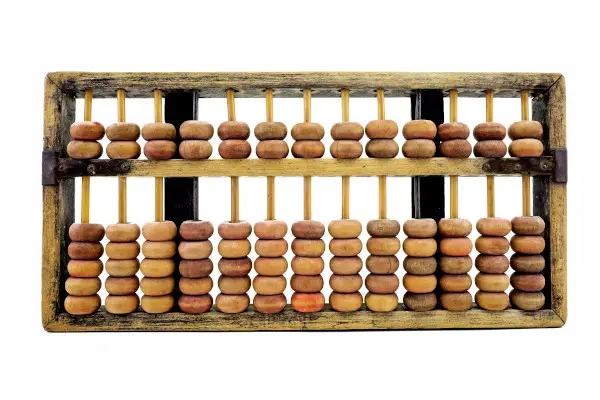

The Abacus, an ancient calculating tool

The abacus, often referred to as the “suanpan” 算盘 in Chinese, is an ancient calculating tool that has played a fundamental role in Chinese mathematics and commerce for centuries. Its origins in China can be traced back to around 2,000 years ago during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

Early abacuses were simple counting boards made of wood or bamboo, with rows of beads or stones arranged in columns. These beads represented different place values, allowing users to perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division through manual manipulation.

The adoption of the abacus revolutionized calculation methods in China, enabling merchants, scholars, and government officials to perform complex arithmetic quickly and accurately. The simplicity and efficiency of the abacus made it an indispensable tool for everyday tasks such as accounting, tax assessment, and trade transactions.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE), the abacus underwent further refinement, with the introduction of standardized designs and instructional manuals to facilitate widespread use and instruction. The proficiency in abacus calculation became a mark of education and intelligence in Chinese society.

Despite the advent of electronic calculators and computers, the abacus remains a symbol of mathematical prowess and cultural heritage in China and other parts of the world. It continues to be taught in schools and used in traditional settings, reflecting the enduring legacy of ancient Chinese ingenuity and innovation in mathematics.

Related reading: The Chinese Abacus and How to Use it – Opens in new tab

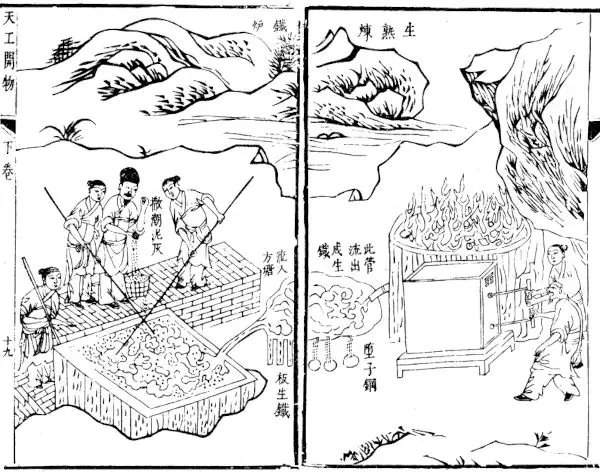

The first known use of a Blast Furnace

The blast furnace, a revolutionary innovation in metallurgy, has its origins in ancient China, dating back to the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Historical records suggest that the Chinese were the first to develop and employ blast furnaces for the smelting of iron ore to produce iron and steel on a large scale. This information is based on the research of Chinese technology historian Donald B. Wagner.

The early Chinese blast furnaces were constructed from clay and brick and operated using a forced draft technique, which involved blowing air into the furnace to increase the temperature of the fire. This allowed for the efficient combustion of charcoal or coke and the reduction of iron ore into molten metal.

The use of blast furnaces in China played a pivotal role in the advancement of iron production, enabling the mass production of iron and steel for various purposes, including tools, weapons, and construction materials. Chinese blast furnaces were renowned for their efficiency and productivity, contributing to the economic prosperity and military strength of the Han Dynasty and subsequent periods.

The technology of blast furnace operation gradually spread from China to other parts of the world through trade and cultural exchange along the Silk Road and maritime trade routes. The diffusion of blast furnace technology facilitated the development of ironworking industries in regions such as the Middle East, Europe, and South Asia, shaping the course of human history and technological progress.

Related reading: The Role of Women in Ancient China: A Journey Through Time – Opens in new tab

Sternpost-mounted Rudder

The invention of the sternpost-mounted rudder, also known as the axial rudder, stands as a transformative innovation in maritime technology that originated in ancient China. Dating back to the 1st century CE during the Han Dynasty, this ingenious device revolutionized the steering and maneuverability of ships, facilitating navigation and exploration on the open seas.

Unlike earlier steering mechanisms such as quarter rudders or steering oars, which were attached to the sides of ships, the sternpost-mounted rudder was affixed to the sternpost, or the vertical post at the back of the vessel. This positioning allowed for greater control and stability, as the rudder could exert more direct influence on the ship’s direction.

The design of the sternpost-mounted rudder consisted of a flat, vertically oriented blade that could be pivoted horizontally for steering purposes. This simple yet effective configuration enabled sailors to navigate more efficiently, adjust course more easily, and respond to changing wind and water conditions with greater precision.

The adoption of the sternpost-mounted rudder revolutionized maritime trade, exploration, and warfare, enabling Chinese sailors to venture further from the coastline and navigate more safely across vast oceans. Chinese navigators used this technological advantage to explore and establish trade routes throughout Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and beyond.

The influence of the sternpost-mounted rudder extended far beyond China, as the technology spread to other maritime cultures through trade and cultural exchange. Its widespread adoption transformed ship design and navigation techniques, shaping the development of seafaring civilizations and facilitating global maritime exploration and commerce.

The Multi-tube Seed Drill

The credit for the invention of the multi-tube seed drill goes back to China in the 2nd century BCE. This innovative device revolutionized farming practices by significantly improving the efficiency and effectiveness of seed planting.

Traditionally, seeds were sown manually by scattering them across fields, resulting in uneven distribution and wastage. The multi-tube seed drill addressed these challenges by automating the seeding process and ensuring precise seed placement at optimal depths.

The design of the multi-tube seed drill featured a wooden frame with multiple seed tubes arranged in rows. These tubes contained seeds and were connected to a series of rotating wheels or gears, which allowed for the controlled release and planting of seeds as the drill moved across the field.

The introduction of the multi-tube seed drill brought about several benefits for farmers. By planting seeds at uniform intervals and depths, it improved crop yield and quality while reducing the amount of seed required. Additionally, the use of a seed drill helped to conserve soil moisture and nutrients, leading to more sustainable agricultural practices.

The widespread adoption of the multi-tube seed drill in China contributed to increased agricultural productivity and food security, particularly in regions with dense populations and limited arable land. Its efficiency and effectiveness propelled advancements in farming techniques and paved the way for further innovations in agricultural machinery.

The impact of the multi-tube seed drill extended beyond China, as knowledge of its design and function spread to other agricultural societies through trade and cultural exchange. Its introduction to Europe during the Middle Ages revolutionized farming practices and played a vital role in the Agricultural Revolution, which transformed the European countryside and spurred economic growth.

“The multi-tube seed drill, introduced during the Song Dynasty, exemplifies China’s ingenuity in agricultural innovation, increasing crop yields and transforming farming practices.”

— Professor Zhang Ming, Agricultural Scientist

Agricultural and Nautical Innovations

| Invention | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Tube Seed Drill | 2nd Century BCE | Revolutionized agriculture with efficient seed sowing for improved crop yields. |

| Sternpost-Mounted Rudder | 1st Century CE | First known use on ships, providing superior maneuverability and control |

Chinese Inventions in Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE)

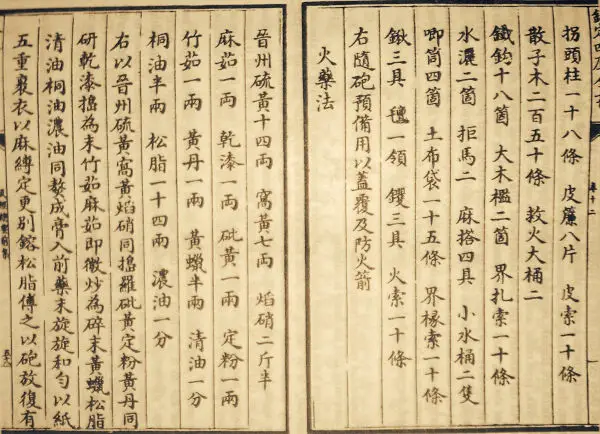

Gunpowder invention and its military applications

Gunpowder, also known as black powder, is one of China’s most transformative inventions, with profound implications for warfare, technology, and global history. The origins of gunpowder trace back to 9th-century China (Tang Dynasty), where Taoist alchemists experimented with various substances in their pursuit of an elixir of life.

Their meticulous documentation of these experiments led to the accidental creation of gunpowder, a potent mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter (potassium nitrate). When ignited, gunpowder undergoes rapid combustion, producing a large volume of hot gas and solid residue. This explosive reaction forms the basis of its use in firearms, artillery, fireworks, and other pyrotechnic applications.

While initially intended for medicinal purposes, gunpowder’s explosive potential soon became apparent. Early applications included rudimentary fireworks and smoke bombs used for signaling.

During the Song Dynasty (10th–13th century CE), Chinese engineers further refined gunpowder technology, developing sophisticated siege weapons and naval artillery that played a decisive role in defending against invasions and asserting Chinese naval dominance in the region.

The dissemination of gunpowder technology to other parts of the world occurred through trade, conquest, and cultural exchange along the Silk Road and maritime trade routes. The introduction of gunpowder to Europe during the Middle Ages triggered a period of military innovation, leading to the development of firearms, cannons, and other gunpowder-based weapons that transformed warfare in Europe and beyond.

The impact of gunpowder extended far beyond the battlefield, influencing technological advancements in metallurgy, chemistry, and engineering. Gunpowder’s role in the exploration and colonization of new territories also had profound geopolitical consequences, shaping the course of world history and globalization.

Related reading: China’s Secret Weapon: Unraveling the Mystery of Gunpowder’s Birth – Opens in new tab

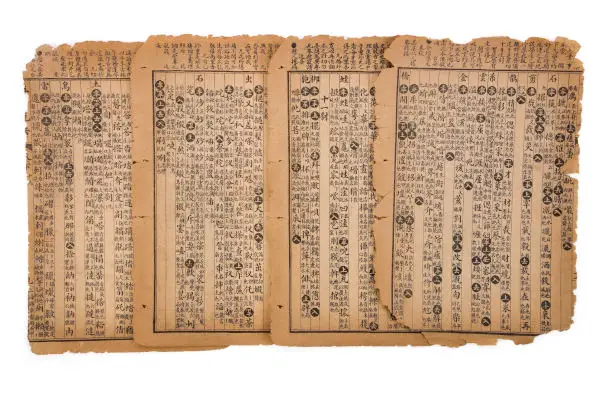

The invention of Woodblock Printing

Woodblock printing, an ancient printing technique originating in China, has had a profound impact on the dissemination of knowledge, culture, and religion throughout history. Dating back to the Tang Dynasty (7th–10th century CE), woodblock printing revolutionized the process of reproducing texts and images, making books and artwork more accessible to a wider audience.

The process of woodblock printing involves carving characters or images into wooden blocks, applying ink or pigment to the carved surface, and then pressing the block onto paper or fabric to transfer the design. This method allowed for the mass production of texts, illustrations, and religious scriptures, facilitating the spread of literacy, scholarship, and cultural exchange.

The earliest known dated example of woodblock printing is the Diamond Sutra, a Buddhist text printed in China in 868 AD. This remarkable achievement demonstrates the early mastery of woodblock printing for text reproduction. The intricate details of the text showcase the precision and skill involved in carving the wooden blocks.

Woodblock printing played a crucial role in the preservation and dissemination of China’s rich literary and artistic heritage, including classics such as the “Dao De Jing” and “The Art of War,” as well as Buddhist sutras and Confucian texts. It also facilitated the spread of Chinese culture and technology to neighboring regions and beyond, influencing artistic traditions in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

The widespread availability of printed materials contributed to the rise of literacy and education, fostering intellectual and cultural exchange among scholars, artists, and craftsmen. Woodblock-printed books, illustrations, and maps became highly prized commodities, valued for their beauty, accuracy, and utility.

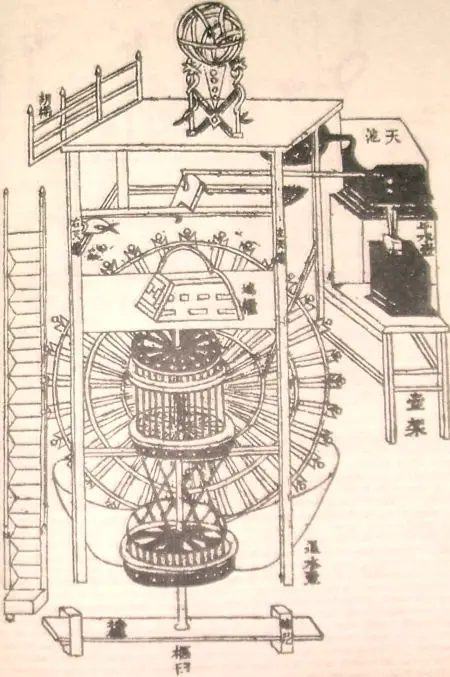

Mechanical clock development during the Tang Dynasty.

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) marked a significant period of innovation and cultural flourishing in ancient China, including advancements in mechanical clock technology. Although mechanical timekeeping devices had been developed earlier, it was during the Tang Dynasty that mechanical clocks began to gain prominence and sophistication.

One of the earliest known mechanical clocks from this period was the “water-driven escapement clock,” attributed to the brilliant engineer and astronomer Yi Xing. This clock, invented in 725 CE, featured a waterwheel mechanism that drove an escapement device, regulating the release of water to power the clock’s movement. The clock was designed to chime at regular intervals, allowing people to track the passage of time more accurately.

Another notable development during the Tang Dynasty was the invention of the “incense clock” or “hourglass clock.” This clock used burning incense sticks, marked at intervals, to measure time as they burned down. The incense clock became a popular timekeeping device in both religious and secular contexts, with variations used in temples, palaces, and homes.

The Tang Dynasty also witnessed advancements in astronomical observation and measurement, which contributed to the refinement of mechanical clock technology. Astronomers and scholars made significant progress in understanding celestial phenomena, such as the movement of the sun, moon, and stars, which influenced the design and functionality of mechanical clocks.

The widespread use of mechanical clocks during the Tang Dynasty symbolized the growing sophistication of Chinese science, technology, and culture. These clocks served not only practical purposes such as timekeeping and scheduling but also had symbolic and ceremonial significance, reflecting the importance of time in Chinese society.

Although many of the early Tang Dynasty mechanical clocks have been lost to history, their legacy endures in the evolution of timekeeping devices and the continued pursuit of precision engineering and measurement.

Early Scientific Instruments

| Invention | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Seismoscope | 132 CE | First known earthquake detection instrument using a pendulum system. |

| Water-Driven Escapement Clock | Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) | Timekeeping device using waterwheel power to regulate water release and measure time. |

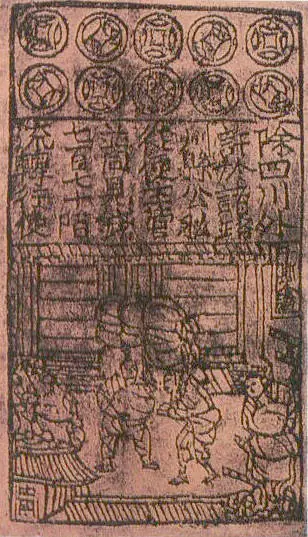

The invention of the earliest known Banknotes

Banknotes, also known as paper money or currency, have a fascinating history that traces back to ancient China. During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the Chinese government issued the first known paper money, known as “jiaozi,” to alleviate the burden of carrying heavy coins for trade transactions.

The introduction of banknotes was driven by the need for a more convenient and standardized medium of exchange in a rapidly expanding economy. Jiaozi was initially issued by merchants and later by the government, backed by deposits of precious metals such as gold and silver.

These early banknotes were typically made from mulberry bark paper or silk and featured intricate designs, watermarks, and security features to prevent counterfeiting. They were issued in various denominations and could be exchanged for goods and services at designated redemption centers.

The use of banknotes flourished during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), with the government establishing a national banking system and issuing official paper currency known as “jiaochao.” These banknotes were widely circulated and accepted for both commercial and tax purposes, further facilitating trade and commerce across China.

Despite occasional periods of instability and currency devaluation, the use of banknotes continued to evolve and expand in subsequent dynasties. The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE) introduced standardized paper currency backed by the state treasury, laying the groundwork for modern banking and monetary systems.

The concept of paper money gradually spread beyond China’s borders, influencing monetary practices in neighboring regions and eventually reaching Europe and other parts of the world. The adoption of paper currency revolutionized global commerce, enabling greater liquidity, flexibility, and efficiency in financial transactions.

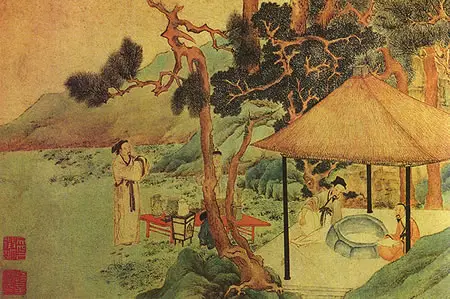

Tea Cultivation and Processing

The origins of tea cultivation and processing can be traced back to ancient China, where the practice of drinking tea dates back thousands of years. According to legend, tea was discovered accidentally by Emperor Shen Nong around 2737 BCE when tea leaves fell into a pot of boiling water he was preparing.

Initially consumed for its medicinal properties, tea gradually became valued for its refreshing taste and stimulating effects, leading to its widespread adoption as a beverage. Tea cultivation began in China’s southwestern regions, particularly in present-day Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, where wild tea plants grew abundantly.

Early Chinese tea drinkers harvested leaves from wild tea trees and processed them by roasting or steaming before steeping them in hot water. Over time, as the demand for tea grew, farmers began cultivating tea plants in more controlled environments, selecting specific cultivars and refining cultivation and processing techniques.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), tea drinking became more widespread and culturally significant, leading to the establishment of tea plantations and the development of tea trade networks. The Chinese Tea and Horse Road, a vast network of trade routes connecting China with Tibet, Central Asia, and beyond, facilitated the exchange of tea, horses, and other goods.

Tea processing methods also evolved during this period, with innovations such as steaming and fermentation introduced to enhance flavor and aroma. Tea artisans experimented with different processing techniques to create a variety of tea types, including green tea, black tea, oolong tea, and white tea.

The dissemination of tea cultivation and processing techniques to neighboring regions, such as Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia, occurred through cultural exchange and trade. Each region adapted tea cultivation and processing methods to suit local climates, soils, and preferences, giving rise to diverse tea cultures and traditions.

Today, tea cultivation and processing remain integral to Chinese culture and heritage, with China being one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of tea.

Related reading: “The Chinese Method of Tea-Making: Your Guide to Gongfu Cha“ – Opens in new tab

Toothbrush

The toothbrush, an essential tool for oral hygiene, has a long history that can be traced back to ancient China. Early forms of toothbrushes in China were made from a variety of materials, including bamboo, bone, and animal hair, and date as far back as the 7th century CE during the Tang Dynasty.

These ancient toothbrushes typically consisted of a small bamboo or bone handle with bristles made from the hair of animals such as boars, horses, or badgers. The bristles were attached to the handle using twine or wire and were often uneven in length and texture compared to modern toothbrushes.

The use of toothbrushes in China was closely associated with oral hygiene practices, particularly within elite circles and among scholars and nobility. The practice of toothbrushing spread gradually among the general population, supported by the growing awareness of dental health and hygiene.

During the Ming Dynasty (14th–17th century CE), toothbrushes became more widely available and affordable, with the invention of toothbrushes made from materials such as bone, wood, or bamboo, with bristles made from natural fibers or plant materials.

Tools and Everyday Inventions

| Invention | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Gunpowder | 9th Century CE | Powerful mixture used in weapons like cannons and rockets, revolutionizing warfare. |

| Abacus | 2nd Century BCE | Calculating tool with rows of beads for arithmetic operations. |

| Toothbrush (China) | 14th Century CE | Brushes with stiffer bristles made from animal hair, a precursor to modern toothbrushes. |

| Tea Cultivation and Processing | 2700 BCE onwards | Originated in southwest China, laying the foundation for global tea culture. |

Chinese Inventions in Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE)

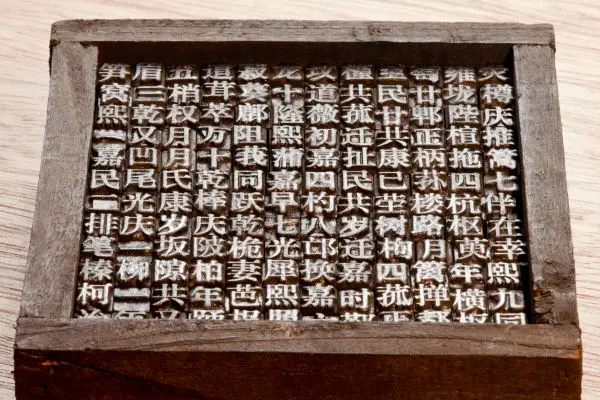

The invention of Movable Type Printing

Movable type printing, a revolutionary advancement in printing technology, was pioneered in ancient China during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). Developed by the artisan Bi Sheng in the 11th century, movable type printing transformed the process of book production, making it faster, more efficient, and more accessible than ever before.

Unlike traditional woodblock printing, which required carving individual characters onto wooden blocks for each page, movable type printing allowed for the reuse of individual characters, reducing the time and labor required for typesetting. Bi Sheng’s movable type system consisted of individual clay characters, each representing a single Chinese character, which could be arranged and rearranged to form text.

The use of movable type printing spread rapidly throughout China, leading to a proliferation of books, pamphlets, and other printed materials. This technological innovation facilitated the spread of knowledge, literacy, and culture, fostering intellectual and artistic advancements during the Song Dynasty and beyond.

Although Bi Sheng’s movable type system was highly effective, it faced limitations in terms of durability and practicality. It was not until the 13th century, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE), that the artisan Wang Zhen developed a more durable movable type system using clay, wood, and metal.

Wang Zhen’s movable type system, known as “wooden movable type,” featured individual characters cast from metal alloys such as bronze or tin and set into wooden blocks for printing. This innovation improved the quality and longevity of movable type printing, paving the way for further developments in printing technology.

The invention of movable type printing had a profound impact on Chinese society, contributing to the democratization of knowledge, the standardization of written language, and the spread of literacy among the population. It laid the foundation for the modern printing industry and played a crucial role in the dissemination of ideas and information during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods in Europe.

“Movable type printing, pioneered during the Song Dynasty, democratized access to knowledge and information, fueling intellectual and cultural advancements across China and beyond.”

— Professor Wang Jian, Historian

Gunpowder Weapons including cannons, rockets, and bombs.

Gunpowder weapons have played a significant role in warfare, revolutionizing military tactics and strategies. The development of gunpowder weapons dates back to ancient China, particularly during the Song Dynasty.

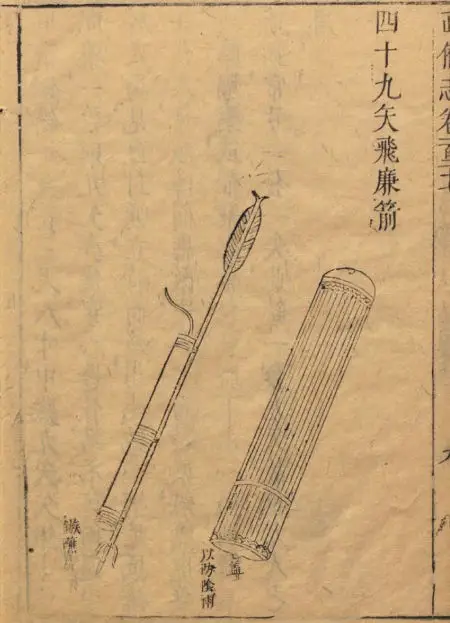

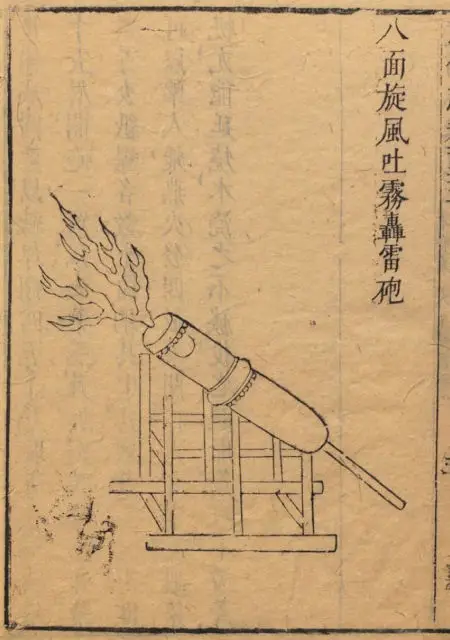

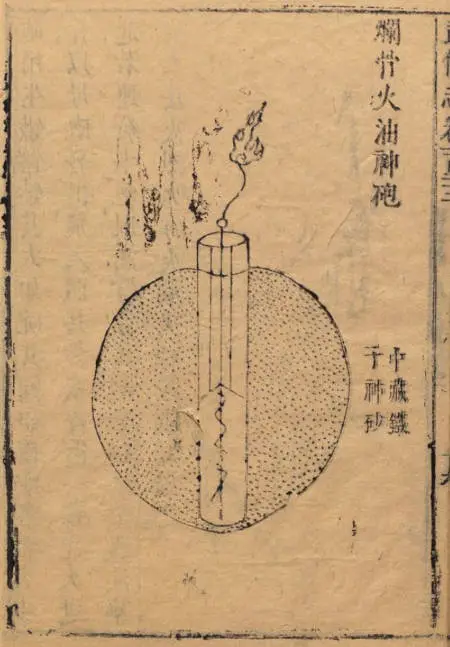

Military engineers during this period found gunpowder to be instrumental in siege warfare, leading to the creation of early forms of rockets, cannons, bombs, and mines. The “Wujing zongyao,” a military manual from 1044 CE, documented the first true gunpowder formula and provided instructions on large-scale production.

Gunpowder was initially used as an incendiary compound, with small packages attached to arrows and lit with a fuse. Additionally, bombs made of gunpowder mixed with scrap iron were launched using catapults, showcasing the diverse applications of gunpowder in warfare.

Gunpowder weapons were extensively utilized by both the Chinese and Mongol forces in the 13th century, highlighting their strategic importance in military conflicts. The continuous efforts by the Song Dynasty to enhance their weapons played a crucial role in their ability to resist Mongol invasions for several decades.

The Mongols, like previous conquerors, were quick to adopt new military technologies by capturing Chinese engineers and gunners. The evolution of gunpowder weapons, from fire-spurting lances to rockets and cannons, marked a significant advancement in military technology during this period.

The utilization of gunpowder in various forms, such as smoke bombs, incendiary bombs, and grenades, demonstrated its versatility and effectiveness in siege warfare and combat scenarios.

“The invention of gunpowder weapons in ancient China transformed warfare, reshaping the balance of power and influencing the course of history for centuries to come.”

— General Li Wei, Military Strategist

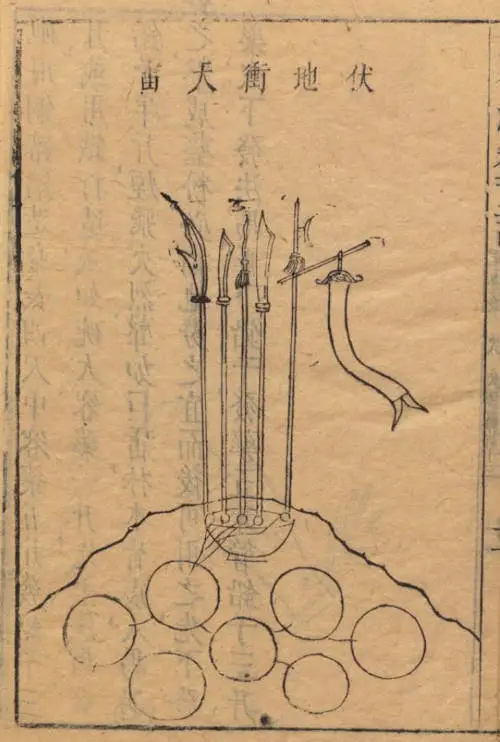

The creation of the first known Land Mine

The concept of the land mine, an explosive device designed to detonate when triggered by pressure or proximity, has ancient roots dating back to China’s Song Dynasty (10th–13th century CE). While the precise origins of the first land mine are not definitively documented, historical records suggest that various forms of rudimentary land mines were used in warfare during this period.

During the Song Dynasty, Chinese military engineers devised various defensive strategies to protect against enemy invasions, including the use of explosive traps and devices buried beneath the ground. These early land mines were typically made from hollow bamboo tubes filled with gunpowder and shrapnel, which detonated upon contact with an enemy’s foot or horse.

The use of land mines during the Song Dynasty is documented in historical texts and military treatises, which describe the deployment of concealed explosives to ambush and deter enemy forces. These primitive land mines were strategically placed along fortified walls, mountain passes, and other strategic locations to impede enemy advances and disrupt troop movements.

While the effectiveness of early land mines was limited compared to modern counterparts, their psychological impact and strategic value were significant. Land mines served as formidable deterrents against enemy incursions, instilling fear and caution among attackers and forcing them to adopt alternative routes or tactics.

The first known land mine in history represents a milestone in the evolution of military technology, highlighting the ingenuity and innovation of ancient Chinese engineers and strategists. While the use of land mines remains controversial due to their indiscriminate nature and long-term consequences, their historical significance cannot be denied.

“The use of land mines in ancient China during the Song Dynasty demonstrated the strategic ingenuity of military engineers, highlighting the evolving tactics of defensive warfare.”

— General Zhang Wei, Military Historian

Printing and Communication Advancements

| Invention | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Woodblock Printing | 8th Century CE | Early printing technique using carved wooden blocks for prints on paper or fabric. |

| Movable Type Printing (China) | 1040 CE | Bi Sheng’s invention using clay characters, a precursor to Gutenberg’s movable type printing. |

End Words

In conclusion, our exploration has taken us on a fascinating journey through China’s remarkable inventions. From the ingenious water-driven escapement clock to the world-changing innovation of gunpowder, China’s contributions have left an indelible mark on the course of human history.

Whether it’s the precision of the multi-tube seed drill or the elegance of the sternpost-mounted rudder, these inventions continue to influence our world today. As we delve deeper into China’s rich heritage of innovation, we gain a profound appreciation for the ingenuity and creativity that have shaped our past and continue to inspire us in the present.

Additional resources

- History of Papermaking Around the World

- Silk in Antiquity

- Magnetic Compasses and Chinese Architectures

- Reconstruction Design of the Detecting Mechanism of Zhang Heng’s Seismoscope

- Review of Reconstruction Designs of Zhang Heng’s Seismoscope

- Curran J. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. BMJ. 2008 Apr 5;336(7647):777. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39527.472303.4E. PMCID: PMC2287209.

- A. White, E. Ernst, A brief history of acupuncture, Rheumatology, Volume 43, Issue 5, May 2004, Pages 662–663, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keg005

- Tea: A Global History

- Stern-Mounted Rudder

- Wooden movable-type printing of China

- Commerce and Society in Sung China

- Gunpowder and Firearms

- The Blast Furnace: 800 Years of Technology Improvement

- Donald B. Wagner: Iron and Steel in Ancient China. DOI:10.22439/cjas.v8i1.1829

- Planted to kill: A brief history of landmines

- Kumar, Jayanth V. (2011). “Oral hygiene aids”. Textbook of preventive and community dentistry (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 412–413. ISBN 978-81-312-2530-1.

- Hwang, Z.-H., Yan, H.-S., and Lin, T.-Y.: Historical development of water-powered mechanical clocks, Mech. Sci., 12, 203–219, https://doi.org/10.5194/ms-12-203-2021, 2021.

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Feature Image from Depositphotos