Imagine living in a world where the slightest misstep—be it theft, insult, or even a poorly chosen word—could cost you your freedom, your dignity, or even your body. In ancient China, the law wasn’t just a set of rules. It was an iron framework built to maintain order in a vast, diverse empire. From the imperial palace to the remote countryside, the state’s grip on justice was firm—and often merciless.

Ancient Chinese society was built on order, hierarchy, and obedience. Every person had a place. Every action had a consequence. Punishment was not just about correcting wrongs; it was about preserving harmony in a rigidly structured world. In this context, harsh penalties weren’t unusual—they were expected. In fact, they were considered essential tools for keeping society from unraveling.

The law in imperial China served multiple masters. It answered to emperors obsessed with control, ministers guided by philosophical doctrines, and a population that feared chaos above all else. The result? A justice system that could be both breathtakingly precise and terrifyingly brutal.

But was it truly justice?

This question haunts the history of ancient Chinese punishment. On one hand, the laws were designed to be fair, consistent, and deeply moral—at least in theory. On the other, the methods used to enforce them often crossed into cruelty, targeting the body, the soul, and the very identity of the accused.

Some punishments served as public warnings. Others aimed to erase a person’s dignity entirely. Whether through branding, mutilation, exile, or execution, the state made its power visible—and unforgettable. Yet, even in these harsh times, there were moments of compassion, voices of resistance, and efforts at reform.

So was ancient Chinese justice a brutal necessity—or an exercise in authoritarian cruelty?

The answer lies in the stories, philosophies, and punishments that shaped the empire for over two thousand years. Let’s take a closer look.

The Roots of Punishment: Why Such Harsh Measures?

The roots of China’s harsh penal system stretch deep into antiquity. Long before the unification of the empire, early dynasties like the Shang and Zhou were already developing systems of law to regulate society. These laws weren’t simply administrative—they were moral judgments carved into bronze vessels or written on bamboo slips, often laced with ritual meaning.

One of the earliest surviving legal codes, the Zhouli (Rites of Zhou), shows how law was intertwined with cosmic order and social duty. The first complete surviving legal code is the Kaihuang Code of the Sui dynasty, which later influenced the Tang Code—one of the most comprehensive and enduring legal frameworks in Chinese history

These early codes were not just about punishing crime but about reinforcing the social fabric. It was about restoring balance between heaven, earth, and mankind.

By the time of the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE), China saw the emergence of a fully codified, centralized legal system. The Qin, eager to unite the realm under one authority, introduced standardized laws across all regions. Their legal code was harsh, detailed, and uncompromising. Severe punishment was seen as the quickest way to instill obedience in a vast and newly unified empire.

This approach left a deep imprint on Chinese legal tradition for centuries to come.

The Influence of Confucianism and Legalism on Punishment

Two major schools of thought—Confucianism and Legalism—competed to shape the philosophy behind punishment in ancient China. Their clash is key to understanding why punishments were so often extreme.

Legalists believed that people were inherently selfish and needed strict laws to behave. For them, fear was the best teacher. Harsh punishments served as deterrents, keeping citizens obedient and society stable. Famous Legalist thinkers like Han Feizi argued that even minor crimes should be punished severely to prevent greater offenses down the road.

Confucians, on the other hand, placed more emphasis on virtue, education, and moral development. Confucius himself stressed ren (humaneness) and believed rulers should lead by moral example, not by terror. In an ideal Confucian society, punishments would be rare—needed only when moral guidance failed.

But in practice, dynasties often blended both views. The state relied on Legalist enforcement to maintain order, while using Confucian values to justify the ruler’s authority. This uneasy marriage meant that laws were framed in moral terms, but enforced with an iron fist.

Social Hierarchy and the Law: Who Was Punished and Why?

In ancient China, not everyone stood equal before the law. Punishment was deeply tied to your social status, gender, and role in society. The lower your rank, the more likely you were to face the full weight of imperial justice.

Commoners, peasants, and slaves bore the brunt of physical punishments. Mutilation, flogging, and forced labor were often their fate for crimes that might only earn a reprimand—or a fine—for the elite. A scholar-official might lose his post for corruption. A farmer could lose a limb for stealing grain.

Women, too, were judged not only by the law but by Confucian expectations of virtue and obedience. A woman who defied family norms could be punished more severely than a man committing the same offense.

Age also mattered. Children could be spared certain penalties, while the elderly might be shown mercy—but only within limits.

In this system, justice was not blind. It saw everything: your title, your gender, your connections. And it judged accordingly.

The Five Punishments: Unpacking the Infamous Wǔ Xíng

In imperial China, the Wǔ Xíng (五刑), or Five Punishments, formed the backbone of criminal penalties for centuries. These were not symbolic slaps on the wrist. They were physical, permanent, and deliberately brutal. Designed to punish the body and brand the soul, the Wǔ Xíng were meant to shock society into obedience. Each punishment told a story—not just of guilt, but of the state’s total control over one’s body and future.

Tattooing: Marking Criminals for Life

The first of the Five Punishments was tattooing, known as mò xíng (墨刑). Criminals had characters inked or carved into their faces—often denoting the specific crime they committed. These tattoos were visible to everyone. They turned people into walking announcements of their guilt.

This punishment was more than skin deep. In a society where reputation and family honor mattered greatly, facial tattoos were devastating. They signaled permanent exclusion. No matter how much time passed, no matter how remorseful the person became, the tattoo remained. It erased a person’s social identity and replaced it with shame.

Tattooing was often used for minor crimes—petty theft, disorderly conduct—but its effects lasted a lifetime.

Nose Cutting: A Permanent Mark of Shame

Next came nose cutting, or yì xíng (劓刑). This was not just mutilation—it was humiliation. The nose, prominent and visible, was a marker of human dignity. Removing it sent a powerful message: you are no longer a full person in the eyes of society.

Nose cutting was reserved for more serious offenses like forgery, fraud, or betrayal. It could also be applied to repeat offenders who had already been tattooed. The disfigurement was intended to ensure the person could never again hide their past or escape the consequences of their actions.

In many cases, the punishment extended beyond the criminal. Families, too, bore the social stigma. Parents, spouses, and children often suffered by association.

Foot Amputation: Mobility Taken Away

The third punishment, foot amputation (yuè xíng, 刖刑), went even further—taking not just pride, but independence. A person who lost one or both feet could no longer travel freely, work, or live without assistance. This physical limitation made reintegration into society nearly impossible.

Used primarily for serious crimes like robbery or assault, foot amputation also served to isolate the offender. In a largely agrarian society where walking was the main mode of transportation, this punishment effectively imprisoned people in their own homes—or left them begging in the streets.

It was a slow, grinding sentence—social death without formal execution.

Castration: The Ultimate Personal Loss

Few punishments evoked as much dread as castration, or gōng xíng (宮刑). This was not just a bodily injury—it was a total erasure of masculinity, lineage, and family future. In a Confucian world where continuing the family line was a sacred duty, castration was a fate worse than death.

The punishment was used for crimes against the state, treason, and sometimes for offenses against the imperial family. It was also a common punishment in the early Han Dynasty’s bureaucratic system, where castrated men (eunuchs) could be forced into palace service.

But the price was unimaginable. Beyond the physical trauma, castration cut a man off from the possibility of legacy, marriage, and social acceptance.

It turned a criminal into a tool of the state.

Death: The Final Sentence

The last and most severe of the Wǔ Xíng was, of course, death—dà pìng (大辟). Capital punishment came in many forms: beheading, hanging, strangulation,or even more gruesome executions like lingchi (death by a thousand cuts). The method often depended on the dynasty, the crime, and the criminal’s social standing.

But death was not always the worst penalty in practice. For some, mutilation or disgrace left longer-lasting scars. Death, while final, could be swift. Still, it carried its own horrors: bodies mutilated, families disgraced, ancestral rites disrupted. In traditional Chinese belief, an intact body was needed for a peaceful afterlife—so execution could also mean spiritual damnation.

It wasn’t just about ending a life. It was about erasing a legacy.

Related reading: Foot Binding in China: A Tradition That Left Its Mark on History and Humanity – Opens in new tab

Beyond the Five: Other Shocking Ancient Chinese Punishments

While the Wǔ Xíng were the core of ancient Chinese penal codes, they were far from the only punishments used to enforce obedience and maintain order. Across dynasties, emperors and magistrates developed an array of additional penalties—some designed to shame, others to maim, and still others to terrify the masses into silence. These punishments offer a deeper look into the psychology of fear, control, and the human cost of law.

Flogging and Beating: Public Pain and Shame

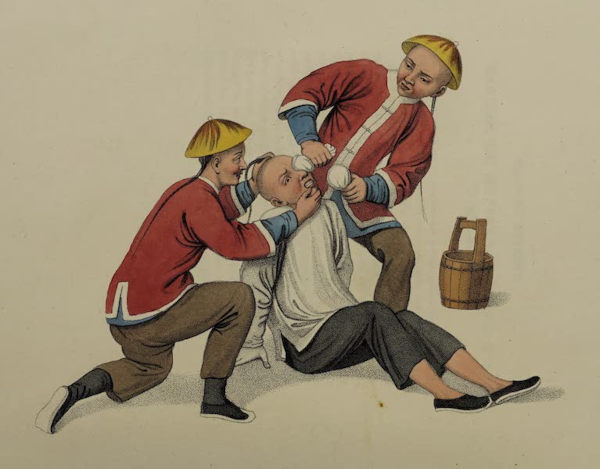

One of the most common punishments in ancient China was flogging, carried out using sticks or bamboo canes. Known as zhàng (杖) or chǐ (笞), these beatings could range from a few dozen to several hundred blows, depending on the crime and the convict’s social status.

Flogging was often performed in public. This visibility was intentional—it wasn’t just a physical punishment, but a public spectacle meant to humiliate. Crowds were invited to watch. Pain became theater. The condemned, stripped and vulnerable, became both lesson and warning.

Flogging was seen as more merciful than mutilation, yet it could be fatal. Internal injuries, infections, and long-term disability were common. In a grim twist, many officials used flogging as a bureaucratic shortcut—a punishment that could be carried out immediately without the need for a lengthy trial.

Banishment and Penal Servitude: Punishment by Exile

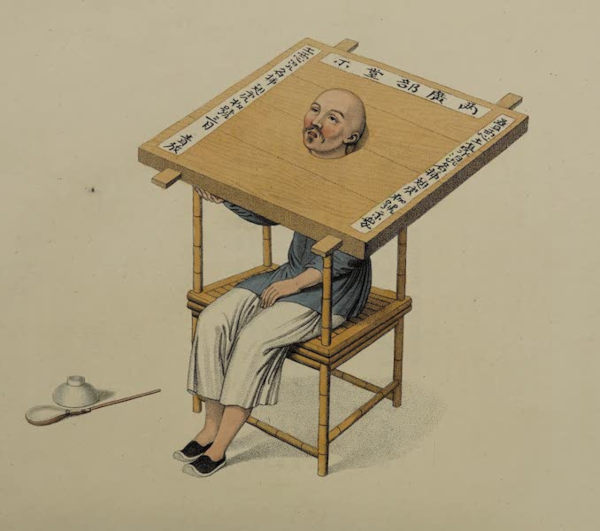

For those not mutilated or executed, there was banishment—a slower, quieter punishment that tore people from their homes and families. Known as liú (流), exile sent criminals to remote, inhospitable regions of the empire—often cold borderlands or disease-ridden swamps.

Exile wasn’t simply relocation. It was erasure. The punished were removed from their social networks, stripped of titles, and cut off from the rhythms of everyday life. For officials, it was the end of a career. For commoners, it meant endless hardship and isolation.

Worse still was penal servitude—forced labor in government-run projects, from canal digging to Great Wall repairs. Criminals sentenced to this fate were often shackled, branded, and watched by armed guards. Survival was never guaranteed.

Both punishments served the state: they got rid of unwanted people while putting them to work.

Torture Devices and Instruments: Tools of Fear

Ancient China employed a variety of torture instruments to extract confessions and intimidate suspects. The jiagun (ankle crusher) was one of the most feared devices. It consisted of three wooden boards tightened around the ankles, gradually crushing the bones to cause unbearable pain without necessarily killing the victim. For women, a less severe but similar device called the zanzhi (finger crusher) was used, which compressed the fingers painfully to force confessions.

Other restraining tools included shackles and manacles for hands and feet, often made of wood or iron, designed to fetter prisoners securely. The xiachuang was a cruel restraint device that immobilized prisoners on a wooden bed with chains and sharp spikes to prevent escape or suicide. These instruments were both practical and psychological weapons, underscoring the power of the state over the individual.

Extreme Penalties: Boiling, Grilling, and Other Horrors

While rare, ancient Chinese records describe some extreme and horrifying punishments used for the worst crimes—especially treason, rebellion, or offenses against the emperor himself.

These included:

- Boiling alive: Criminals were lowered into cauldrons of scalding water or oil.

- Grilling on iron plates: A slow, torturous death by heat.

- Lingchi (death by a thousand cuts): Perhaps the most infamous, this method involved slicing the body over an extended period until death.

- Public dismemberment: Used to send a political message, especially against rebels or assassins.

Though these punishments were rare and often ceremonial, they played a powerful role in reinforcing imperial authority. Their horror lived on in oral tales, historical chronicles, and the terrified imagination of the populace.

Even the threat of such punishments was enough to keep many in line.

Justice or Deterrence? The Purpose Behind the Pain

Why were punishments in ancient China so severe, so public, and so often irreversible? To understand the intent behind these brutal penalties, we must go beyond the physical and examine what the state hoped to achieve. Ancient Chinese rulers didn’t just punish to correct—they punished to control, to instill fear, and to maintain an unshakable social order. Justice, in this context, wasn’t always about fairness. It was often about deterrence.

Punishment as a Deterrent: Scaring Society Straight

The primary goal of many ancient punishments was not to reform the individual, but to prevent others from following in their footsteps. In a society where public shame could ruin a family name for generations, the state weaponized fear as a tool of governance.

Visible punishments—tattooing the face, cutting off the nose, parading the condemned through crowded streets—were warnings in motion. Each punishment served as a living billboard for state authority: Break the law, and this could be you.

This strategy wasn’t unique to China, but it was particularly refined there. The belief was simple and brutally effective: the more terrifying the punishment, the fewer the crimes. Public beatings, executions, and mutilations didn’t just punish individuals. They told the masses, We are watching.

Maintaining Order: Power, Authority, and Control

At its core, the legal system in imperial China was a reflection of political power. The emperor was the “Son of Heaven,” and law was an extension of his divine mandate. Any threat to social harmony—whether theft, disobedience, or dissent—was also seen as a threat to imperial authority.

Punishment was therefore not just a legal matter, but a political one. Rebellions were crushed with extreme cruelty not simply to eliminate rebels, but to send an unambiguous message: The emperor cannot be defied.

Even small infractions were treated with gravity if they challenged the social hierarchy. A servant talking back to a master, or a woman violating familial duty, could face harsher penalties than the crime might seem to warrant. The goal wasn’t proportional justice—it was the preservation of control.

Law, in this context, acted less like a shield for the people and more like a sword for the state.

Psychological Impact: Punishing the Body, Shaming the Soul

Ancient Chinese punishments didn’t stop at physical harm. They were engineered to reach deeper—into the mind, the identity, and the soul. Shame was a core element of the process.

Confucian values emphasized personal virtue, family honor, and social reputation. Punishments were crafted to destroy these. Facial tattoos marked you forever. Castration ended your bloodline. Exile cut you off from your ancestors’ graves—an unthinkable fate in a culture that valued ancestral worship above all.

Even for those who survived their punishment, reintegration into society was rare. The physical scars were only the beginning. Many faced lifelong exclusion, poverty, or suicide. The message was clear: forgiveness might come from the gods, but rarely from the law.

This psychological warfare made the legal system not just a structure of control, but a deeply internalized source of fear. People didn’t obey the law only because they feared the state—they feared becoming that person, branded, broken, and forever outside the moral order.

The Push for Mercy: Calls for Reform in Ancient Times

Despite the severity of ancient Chinese punishments, not everyone agreed that fear and pain were the best tools for justice. Over time, voices emerged—philosophers, reformers, even ordinary citizens—who questioned the cruelty and called for change. Their influence didn’t erase harsh penalties overnight, but they planted powerful seeds of reform. These moments of mercy in a system built on fear show that even in ancient times, compassion had its champions.

Confucian Compassion: Philosophers Against Cruelty

Confucianism, while often seen as conservative, placed strong emphasis on moral behavior, family values, and humane governance. For Confucian scholars, justice wasn’t just about punishing wrongdoers—it was about cultivating virtue in both ruler and subject. They argued that excessive cruelty bred resentment, not respect.

Philosophers like Mencius (Mengzi) openly criticized legal systems that relied too heavily on violence. He believed that a good ruler led by example, not terror. Laws, he said, should align with ren (仁)—the Confucian ideal of humaneness and empathy.

While Legalist thinkers like Han Feizi pushed for strict, fear-based rule, Confucians argued for leniency, proportional punishment, and rehabilitation over mutilation. They didn’t reject punishment entirely, but they wanted it guided by ethics rather than vengeance.

This tension between Confucian mercy and Legalist control remained at the heart of Chinese legal thought for centuries.

The Story of Ti Ying: A Daughter’s Plea Changes the Law

One of the most moving stories of early legal reform comes from the Han Dynasty, involving a courageous young woman named Ti Ying (缇萦). Her father, a physician, was sentenced to one of the Five Punishments—castration—for a legal infraction.

Rather than accept his fate, Ti Ying wrote a passionate petition directly to Emperor Wen of Han. She didn’t just beg for mercy—she reasoned with the emperor. She argued that such brutal punishments destroyed families, ruined futures, and went against the values of filial piety and humanity.

Her letter was heartfelt and brave, especially coming from a woman in a deeply patriarchal society. And it worked.

Emperor Wen was so moved that he pardoned Ti Ying’s father. More importantly, her plea helped inspire a broader reconsideration of harsh penalties, especially mutilation. Ti Ying became a symbol of moral courage—and a rare but powerful example of how ordinary people could shape imperial policy.

Emperor Wen’s Reforms: From Mutilation to Corporal Punishment

The Han Dynasty, especially under Emperor Wen (r. 180–157 BCE), marked a major turning point in the evolution of Chinese law. Deeply influenced by Confucian ideals and stories like Ti Ying’s, Emperor Wen initiated reforms that reduced the use of mutilating punishments.

He replaced three of the Five Punishments—tattooing, nose cutting, and foot amputation—with corporal beatings, which, while still painful and humiliating, did not leave permanent physical damage. This shift was groundbreaking. It signaled a new direction for the legal system: one that still punished, but with more concern for human dignity.

Wen’s reforms didn’t eliminate cruelty from the legal system, but they softened its edges. He showed that an emperor could be both strong and compassionate—a message that resonated across later dynasties.

In many ways, this balance between justice and mercy became a lasting theme in Chinese governance. Reform wasn’t always swift or widespread, but the idea that punishment could be tempered by ethics endured.

Who Faced the Worst? Punishment and Social Status

Justice in ancient China was not blind. It looked closely—at your title, your gender, your age, even your connections. Though the law appeared strict and absolute, its application was often shaped by the rigid social hierarchy of the time. In a deeply stratified society, punishment wasn’t always about the crime. It was also about who you were.

The Law for Commoners vs. Elites: Double Standards

From the earliest dynasties, nobles and officials were treated differently under the law. While commoners might be flogged, mutilated, or executed for theft or disobedience, members of the elite often faced lighter consequences—or were granted the chance to buy their way out.

Privilege could mean exemption from the harshest penalties. Scholar-officials who committed crimes might be demoted, exiled, or fined rather than tortured or killed. There were even legal codes that allowed officials of certain ranks to be spared execution altogether.

This wasn’t just favoritism—it was also strategic. Educated elites were the backbone of the bureaucracy. Killing too many of them could destabilize the empire. So while Confucian ideals emphasized fairness and moral leadership, in practice, the rich and powerful often walked away with lighter punishments.

For commoners, however, the law was brutal and immediate. A peasant stealing grain could face dismemberment or death, while a corrupt magistrate might only face a reprimand. Justice, for many, was a matter of class.

Gender and Age: Were Some Groups Spared?

Women and children occupied a complicated place in the justice system. On the one hand, Confucian ideals promoted the protection of women, especially those seen as virtuous mothers or obedient wives. On the other hand, women who violated social norms—through adultery, rebellion, or even speaking out—were often punished harshly, sometimes more so than men.

Punishments for women were sometimes adapted to “protect modesty,” such as indoor beatings or execution by hanging rather than beheading. But these were small mercies. In cases of infidelity or defiance, women could be drowned, dismembered, or forced into slavery.

Children were generally spared the harshest punishments, particularly very young offenders. Those under a certain age—usually 7 to 10 years old—were often considered incapable of full moral understanding and were given leniency. Teenagers might be flogged rather than mutilated, but they were still subject to the law.

Filial piety added another layer. Children who harmed their parents could face extreme penalties, while parents who abused their children were less likely to be punished. Age and gender mattered—but only within the framework of maintaining social order.

Related reading: The Role of Women in Ancient China: A Journey Through Time – Opens in new tab

Special Groups and Exemptions in Ancient Law

Certain individuals—because of their position, service, or symbolic role—were granted legal exemptions or special treatment.

- Imperial relatives could be shielded from the full force of the law, especially if their crimes were deemed politically sensitive.

- Officials holding high rank were often judged by internal administrative courts, sparing them public humiliation or mutilation.

- Military heroes, especially those with recent victories, were sometimes pardoned for offenses as a reward for service.

- Pregnant women were granted postponements for execution until after childbirth, a rule reflecting a mix of pragmatism and moral optics.

- Monks and nuns, depending on the dynasty and the emperor’s view of religion, were sometimes tried under different legal procedures or exempted from military service and taxation.

Even among criminals, there was a ladder—and not everyone started from the same rung. While harsh punishments defined much of imperial China’s legal system, they weren’t applied evenly. For many, it wasn’t just what you did—it was who you were when you did it.

Mercy in the Middle of Mayhem

Despite the brutality that defined much of ancient Chinese justice, the legal system also had room—however narrow—for mercy. Acts of clemency were not unheard of. In fact, within the rigid world of law and punishment, there existed glimmers of compassion, strategically timed or deeply emotional. Mercy, when it came, was often celebrated, remembered, and retold as a sign that even in a harsh system, humanity could break through.

Imperial Amnesties on Enthronements and Birthdays

One of the most anticipated forms of mercy came from the very top—the emperor himself. During significant imperial events, such as enthronements, royal birthdays, or major festivals like the Lunar New Year, it was common for emperors to declare general amnesties.

These proclamations could commute death sentences, release prisoners, or reduce harsh punishments. While not everyone benefited—especially those convicted of treason or serious crimes—these acts symbolized the emperor’s benevolence and moral virtue.

For the people, these amnesties weren’t just legal events. They were moments of hope. Families reunited. Exiles returned. Some men who had lived under the shadow of execution suddenly found their lives restored.

These gestures also reinforced the Confucian ideal of a “parent-like” ruler—firm when needed, but capable of forgiveness.

Silver for Skin: Redemption Payments and Buying Back Body Parts

In some cases, punishment could be avoided—if one could pay the price.

During certain dynasties, especially in the Han and Tang periods, people convicted of lesser crimes could pay fines or redemption fees in place of receiving physical punishments. This was sometimes referred to as “silver for skin.”

For example, instead of enduring 100 blows of the cane, a person might pay a certain weight in silver to satisfy the penalty. In some cases, even mutilating punishments like tattooing or amputation could be avoided through a hefty payment.

Naturally, this system favored the wealthy and further highlighted the divide between rich and poor. But it also provided a channel—however limited—for second chances. A merchant with means might escape lifelong disfigurement, while a poor farmer had no such option.

Still, even this uneven mercy reflected a growing idea: punishment didn’t always have to scar the body to be effective.

Petitions, Motherly Pleas, and the Power of Righteous Tears

Sometimes, mercy came not from law, but from emotionally powerful appeals.

Family members—especially mothers—were known to submit passionate petitions pleading for their loved ones. These documents were often handwritten, filled with sorrow, and grounded in Confucian language about filial piety, family duty, and loyalty to the emperor.

A famous example is the story of Ti Ying, whose plea to spare her father from mutilation helped trigger major reforms (as discussed earlier). But she was not alone. Many such pleas were sent, and while not all were successful, some moved magistrates—or even emperors—to commute sentences.

The “righteous tear” held symbolic power. In a system where honor and reputation were everything, a heartfelt appeal could tip the balance between death and survival.

This emotional dimension to justice—where law met heart—added complexity to the legal system. Mercy was not guaranteed, but it was possible. And for many, that sliver of hope was enough to keep trying.

Comparing East and West: Was Ancient China Uniquely Cruel?

When reading about branding, castration, or boiling criminals alive, it’s natural to wonder: was ancient China unusually cruel? Or was it simply part of a broader global reality, where punishment everywhere was designed to be harsh, public, and terrifying?

To answer that, we have to look outward—to Rome, Persia, medieval Europe—and inward, at China’s own evolving philosophies of justice. What we find is a complex picture where culture, belief, and politics shaped how civilizations punished—and why.

Ancient Chinese vs. Western Punishments: A Cultural Comparison

In ancient China, punishment was deeply rooted in Confucian order and Legalist control. The goal wasn’t just retribution—it was to scare others into obedience and maintain social hierarchy. Physical mutilation was common, and shame played a major role. Criminals were often marked, exiled, or paraded before the public.

In contrast, Western civilizations, especially ancient Rome and Greece, leaned heavily on public executions and gladiatorial spectacle. Roman crucifixions, for example, were brutal and designed for mass viewing. In Greece, while punishments could be severe, exile and fines were often preferred for the elite. Like China, social status played a huge role in who got punished—and how.

Medieval Europe, centuries later, mirrored much of China’s cruelty. Torture was formalized in the Inquisition, with devices designed to extract confessions. Executions were public and theatrical—hangings, burnings, and dismemberment were common.

Where ancient China differed was in its philosophical contradictions. Legalists supported severe, standardized punishment. But Confucians constantly pushed back, arguing for mercy, education, and moral development. These conflicting ideologies created a unique tension in Chinese law—harsh on paper, yet with space for compassion, at least in theory.

Global Context: Cruelty in Other Ancient Civilizations

Cruelty in punishment was not uniquely Chinese—it was a global phenomenon. Most ancient societies treated justice as a visible, often violent process meant to control behavior and protect rulers.

- In Babylonia, the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1750 BCE) prescribed death or mutilation for a wide range of offenses—an eye for an eye was more than a metaphor.

- In ancient India, texts like the Manusmriti included caste-based punishments that were deeply unequal and often humiliating or fatal for lower castes.

- In Aztec civilization, human sacrifice was considered a form of religious justice—executions were public, ritualized, and frequent.

- In ancient Egypt, treason and theft could lead to amputation, burning, or impalement. While their records show some mercy for certain groups, cruelty was still common.

What set China apart was the codification and systematization of punishments. The Wǔ Xíng (Five Punishments) were clearly defined, often state-mandated, and used across dynasties for centuries. This level of legal continuity—and the philosophical debates that came with it—made Chinese punishment distinctive, if not uniquely cruel.

In short, ancient China was not an outlier in cruelty. Rather, it was part of a global landscape where the whip, the blade, and the spectacle of pain were common tools of rule. But China’s legal evolution, philosophical introspection, and eventual reforms also showed that even within a brutal system, there was room for reflection—and change.

Legacy and Lessons: What Can We Learn Today?

The legacy of ancient Chinese punishment lives on—not in the form of tattooing or amputation, but in the legal principles, cultural memory, and national identity that have evolved from those harsh roots. By understanding how ancient justice was practiced, and how it has changed, we gain valuable insight into the progress of law, the importance of human dignity, and the delicate balance between control and compassion.

How Ancient Punishments Shaped Modern Chinese Law

Today’s Chinese legal system is worlds apart from the mutilating punishments of the Qin or Han dynasties. But the foundations laid thousands of years ago still matter. Many legal philosophies and administrative structures that began in antiquity have influenced how modern law is structured and enforced.

For example, the idea of codified law, where specific crimes correspond to specific punishments, dates back to the early dynasties. The notion that the law should serve the state’s stability—rather than the individual’s rights—has persisted in some form throughout Chinese legal history.

However, modern China has moved away from corporal punishment and towards fines, imprisonment, and rehabilitation. Influences from Western legal systems, particularly during the 20th century, combined with internal reform movements, have gradually pushed the justice system toward greater emphasis on procedure, evidence, and rights—though not without criticism or ongoing challenges.

The journey from the Wǔ Xíng to civil codes and court trials reminds us that legal systems evolve with society. What was once acceptable—even praised—is now widely seen as a violation of basic human rights.

Remembering the Past: Museums, Archaeology, and Popular Culture

China does not hide its punitive past. In fact, it is preserved and examined in museums, exhibitions, and historical dramas that reflect a fascination with the extremes of ancient justice.

Museums across China display replicas of torture devices, legal codes carved into stone, and accounts of famous punishments. Archaeological digs have unearthed prison sites, iron shackles, and burial grounds that confirm just how systematized punishment once was.

Television dramas, historical novels, and films often portray imperial courts, dramatic trials, and the moral dilemmas faced by judges. These stories capture the tension between loyalty and law, justice and cruelty. While dramatized, they spark public interest in the human stories behind legal history.

Rather than erase the painful parts of its past, China seems to be engaging with them—interpreting them through art, scholarship, and conversation. The past becomes a mirror, reflecting not just what happened, but how far society has come.

Justice or Cruelty? Reflections for the Modern World

So, were ancient Chinese punishments acts of justice or cruelty?

The honest answer is: both. They were effective in maintaining order, but often inflicted irreversible suffering. They reflected the values and fears of their time—hierarchy, obedience, control. But they also provoked debate, reform, and eventually, rejection.

For us today, the real lesson lies in asking what kind of justice we want to build. Are our systems fair to all? Do they heal or only hurt? How do we balance security with compassion?

Ancient China reminds us that punishment is never just about the person who suffers it—it’s also about the society that allows it. Every scar left on a body was also a mark on the culture that made it possible.

Looking back gives us perspective. Moving forward, we can choose better.

End Words

Ancient Chinese punishments reveal a world where law was both a tool of order and an instrument of fear. Behind every cut, brand, and exile was a story—not just of crime and consequence, but of power, philosophy, and the constant tension between control and compassion.

From the brutal clarity of the Wǔ Xíng to the emotional weight of a daughter’s plea, ancient China’s justice system was far more than a series of punishments—it was a reflection of its time. Confucian ideals wrestled with Legalist harshness. Officials balanced duty with mercy. The people watched, endured, resisted, and remembered.

These stories are more than relics of the past. They echo into the present, asking hard questions: What is justice? Who deserves punishment? Can law ever be both fair and firm?

In studying ancient cruelty, we don’t just uncover pain—we uncover the roots of reform. The journey from mutilation to rehabilitation shows us that even the most entrenched systems can evolve. And perhaps, that is the most enduring legacy of all.

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Photo citation: Mason, George Henry. The Punishments of China. London: Printed for W. Miller by W. Bulmer. 1801.