For centuries, one of the most haunting symbols of beauty in Chinese history was something few would dare to call beautiful today: bound feet. Known as “lotus feet,” this tradition altered the lives—and bones—of millions of women.

Tiny, arched, and often broken, these feet were once seen as the height of feminine elegance. However, underneath the silk shoes and lyrical nicknames was a great deal of mental and physical suffering.

Foot binding began in childhood, usually before a girl reached seven. It was a rite of passage, wrapped in blood-soaked bandages and motivated by cultural values. Mothers handed it down to daughters with a mixture of pride and grief. As a result, some people spend their whole lives limping, tolerating, and surviving.

Still, it wasn’t only about pain. Bound feet became entangled with ideas of honor, purity, and social mobility. Women with the “perfect” three-inch golden lotus were seen as more desirable brides. Beauty and suffering were stitched tightly together—both admired and expected. This duality, both disturbing and fascinating, is part of what continues to hold our attention today.

Foot binding has long since disappeared from daily life in China, yet it remains one of the most talked-about and analyzed traditions in Chinese history. Why? Because it reveals how powerful culture can be. How an entire society can uphold a practice that, from today’s perspective, seems unthinkable.

The tradition touches on universal themes: the pressure to conform, the pain women endure in the name of beauty, and how deeply social status can shape personal choices. Scholars, artists, and everyday readers continue to ask—how could such a painful custom persist for over a thousand years?

It also sparks deeper questions about gender, control, and identity. While foot binding was distinctly Chinese, the broader themes resonate globally. From corsets in the West to modern beauty surgeries, the echoes of foot binding can still be felt.

Foot binding isn’t just history—it’s a mirror. One that reflects how far society has come, and how much we’re still grappling with the cost of beauty.

The Origins of Foot Binding

Foot binding is believed to have started during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960 AD), but it gained momentum during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). While the exact origin is debated among historians, most agree it began in the imperial courts before spreading to the wider population.

It started as an elite practice—something seen in royal palaces and among wealthy families. In these circles, small feet were a luxury symbol. A woman with bound feet didn’t need to work. She could afford to stay indoors, decorate herself, and move slowly, with delicate grace. Over time, this idea filtered down through society. What began as a fashion among court dancers became a widespread tradition that touched nearly every class of woman in China.

By the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) Dynasties, foot binding was deeply rooted in Chinese society. It became an expected part of girlhood in many regions, especially in northern and central China. Generations grew up knowing no other standard of beauty.

The Legend of the Imperial Concubine and the Golden Lotus

One of the most enduring legends about the origin of foot binding centers on an imperial concubine named Yao Niang. According to popular stories, Yao Niang was the favored consort of Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang. She bound her feet into the shape of a crescent moon and performed an enchanting dance atop a gilded lotus-shaped stage. The emperor was so captivated by her grace that he declared, “lotus springs from her every step,” a phrase that inspired the poetic term “golden lotus” for bound feet.

Other versions of the legend mention Pan Yunu, another celebrated consort, who danced barefoot on a golden lotus floor, further cementing the association between bound feet and the image of the lotus flower.

These romanticized versions of the origin helped frame foot binding not as a brutal act, but as an expression of art, love, and refinement. It was no coincidence that the ideal bound foot came to be called the “golden lotus.” The name itself carried elegance, mystique, and poetic weight.

Stories like this shaped public perception. They softened the painful reality behind the practice and linked it to courtly elegance and imperial admiration. Over time, these legends merged with social expectations, helping the tradition endure for centuries.

Cultural Influences That Sparked the Practice

Foot binding didn’t evolve in isolation. It was heavily influenced by the broader cultural climate of ancient China. Concepts of female modesty, restraint, and obedience were deeply valued, especially under the sway of Confucianism. A woman’s body was expected to be controlled, her movement limited—both literally and symbolically.

Foot binding reinforced these ideals. It physically restricted women’s mobility, keeping them largely within the domestic space. This aligned with Confucian teachings that prized female virtue, silence, and obedience within the family hierarchy.

At the same time, aesthetic values also played a role. Chinese art and poetry of the time often idealized smallness, delicacy, and fragility in women. Bound feet became a canvas for these ideals—a mark of cultivated beauty.

As the practice grew, it became entangled with social class and cultural identity. Having bound feet wasn’t just about beauty—it was about proving one’s refinement, self-discipline, and conformity to social norms. That’s why it endured for so long, even in the face of its obvious physical toll.

| Dynasty | Prevalence | Binding Characteristics | Social Context |

| Song (960–1279) | Began | Originated among elite dancers | Linked to court culture |

| Ming (1368–1644) | High | Narrow shoes, strong emphasis on aesthetics | Marriage and status symbols |

| Qing (1644–1912) | Widespread | Strongest push for “three-inch golden lotus” | Officially discouraged by Manchu rulers |

| Republican Era | Declining | Binding discouraged and banned | Reform and modernization efforts |

Cultural and Social Significance of Foot Binding

In ancient China, beauty was often defined by grace, delicacy, and restraint. Women were admired not for boldness or strength, but for refinement and gentleness. A soft voice, pale skin, slender hands—and above all, tiny feet—were seen as the ultimate signs of feminine allure.

Bound feet became the centerpiece of this aesthetic. A woman with small, carefully shaped “golden lotuses” was considered elegant and desirable. The ideal foot length was just three inches, an almost impossible standard that led to lifelong physical impairment. Yet in that pain and sacrifice, society saw devotion to beauty and family.

Poetry and art reinforced these ideals. Writers praised the swaying, mincing walk of women with bound feet as sensual and modest. Pain became romanticized. A woman’s limp was not seen as a handicap, but as a gentle rhythm that enhanced her femininity. These artistic portrayals blurred the line between suffering and grace.

In this cultural climate, beauty wasn’t simply about appearance—it was about moral character. A beautiful woman was obedient, quiet, and self-controlled. Her bound feet were proof.

Foot Binding as a Symbol of Status and Virtue

Beyond beauty, bound feet were a mark of social class. In wealthier families, they were a sign that a girl didn’t need to work. She was being prepared for marriage, not manual labor. Foot binding, then, became a visible marker of status and upbringing.

For a poor family with ambitions of upward mobility, binding a daughter’s feet was an investment. A girl with well-bound feet had a better chance of marrying into a more prosperous household. It became part of a family’s social strategy.

But it wasn’t just about status—it was about virtue. Bound feet symbolized a girl’s obedience, patience, and willingness to endure hardship. These were qualities highly prized in a wife. To bind the feet was to bind the will to the family, to tradition, and to the role expected of women.

In this way, foot binding was deeply woven into the moral and ethical fabric of Chinese society. It wasn’t merely cosmetic; it was a lived expression of loyalty and virtue.

The Role of Confucianism and Patriarchal Values

Confucianism played a powerful role in shaping the meaning of foot binding. Its teachings emphasized hierarchy, order, and the importance of fulfilling one’s role in society. For women, this meant serving fathers, husbands, and sons with humility and devotion.

Foot binding fit neatly into this worldview. It reinforced female submission and dependence. Women with bound feet were less mobile, more homebound, and thus more easily confined to their domestic roles. This physical limitation was seen not as a flaw, but as a virtue.

The patriarchal structure of ancient Chinese society only deepened the practice. A woman’s worth was tied to her ability to marry well, bear sons, and maintain the family’s honor. Bound feet became a measure of that worth.

Even mothers—who had once suffered the pain themselves—became enforcers of the tradition. They believed they were helping their daughters secure a better future, one that was in line with societal expectations. This generational cycle of love, duty, and cultural pressure made foot binding incredibly hard to break.

In the end, foot binding wasn’t just about feet. It was about control, conformity, and a system that equated suffering with value.

Related reading: The Role of Women in Ancient China: A Journey Through Time – Opens in new tab

The Binding Process: A Harsh Ritual

Foot binding usually began between the ages of four and nine—young enough that the bones were still soft and pliable. This early start was crucial. Older feet were harder to manipulate and more likely to resist the extreme reshaping required to achieve the desired “three-inch golden lotus.”

In many families, the timing was carefully chosen. Autumn or winter was a common season to begin, since cold temperatures numbed the feet slightly, dulling the pain during the first excruciating days. For some girls, it began with celebration. A small ceremony might mark the occasion, disguising the pain to come with sweets, new clothes, or words of encouragement.

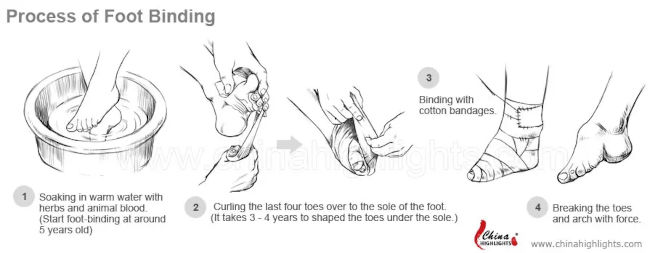

Step-by-Step: How Feet Were Bound

The process of foot binding was brutal and methodical. Once begun, it had to be maintained daily for years.

- Soaking and Cleaning: The child’s feet were first soaked in warm water, often mixed with herbs or animal blood to soften the skin and flesh.

- Toenail Removal or Trimming: Toenails were trimmed to prevent infections. In severe cases, nails were removed entirely to stop them from growing inward as the toes were crushed together.

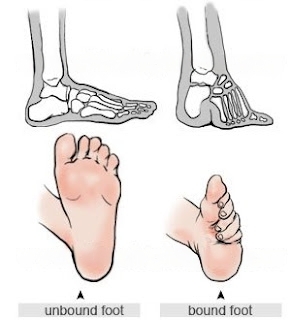

- Breaking and Folding: The four smaller toes were bent underneath the sole of the foot, one by one, until they broke or were forced into a folded position. The arch of the foot was then forcefully bent upward to create a deep curve.

- Binding and Wrapping: Long cotton or silk cloth strips—about 10 feet long—were tightly wrapped around the foot, pressing the toes down and pulling the heel and ball of the foot closer together.

- Securing and Rebinding: The bindings were sewn in place, and the child was made to walk on them immediately to further break the bones and shape the foot. The bandages were removed, cleaned, and reapplied regularly—sometimes daily—to maintain the shape and prevent infection.

This ritual was repeated for months, often years, until the desired size and shape were achieved. The ideal was a foot no longer than a man’s thumb.

Tools, Materials, and Methods Used

The most common materials used were long strips of cloth, usually white cotton, although wealthier families might use silk. These bindings had to be strong enough to hold the foot in place but breathable enough to reduce risk of infection.

Some families used herbal pastes to treat open sores or reduce swelling. Alum powder and other antiseptics were sometimes applied to keep wounds from festering. In certain regions, custom wooden shoes or iron foot molds were used to help maintain the shape.

Needles, scissors, and knives were kept nearby—not for medical use, but to cut bandages or, grimly, to drain abscesses when infections inevitably formed.

The Physical Pain and Health Consequences

The pain was immediate and severe. Bones cracked. Skin tore. Infection was common, especially in the early stages. In some cases, toes rotted and fell off. For a small percentage of girls, the process resulted in permanent disability or even death due to gangrene.

Long-term consequences were just as serious. Women with bound feet often lived in chronic pain. They developed balance problems, deformed knees and hips, and were more prone to falls and broken bones in old age.

Walking was difficult, often painful. Many women could only shuffle in small steps, placing immense strain on the rest of the body. Running, climbing stairs, or standing for long periods became almost impossible.

Coping Mechanisms and Family Roles in the Process

Despite the suffering, families—especially mothers and grandmothers—persevered in maintaining the ritual. Many saw it as a necessary sacrifice for the girl’s future.

Girls coped in various ways. Some were given toys or treats as rewards for endurance. Others were told stories about famous beauties with bound feet to give them hope and purpose. Pain was normalized. Crying was discouraged. Strength and silence were praised.

In wealthier households, daughters were pampered during the binding years. Servants carried them. Their feet were massaged. But in poorer families, girls were expected to help with chores, even while in pain. The contrast between classes was stark.

The Role of Professional Foot-Binders and Family Traditions

In some regions, professional foot-binders—usually older women with experience—were hired to oversee the process. They knew the techniques to break bones just right, and how to spot early signs of infection. Their skills were passed down like a craft.

In many cases, however, foot binding was done at home. It became a family tradition, passed from mother to daughter, generation after generation. Some mothers wept as they bound their daughters’ feet. Others steeled themselves, believing it was the only way to ensure a good marriage and a secure life.

Despite its cruelty, foot binding was seen not as an act of violence, but of love and duty.

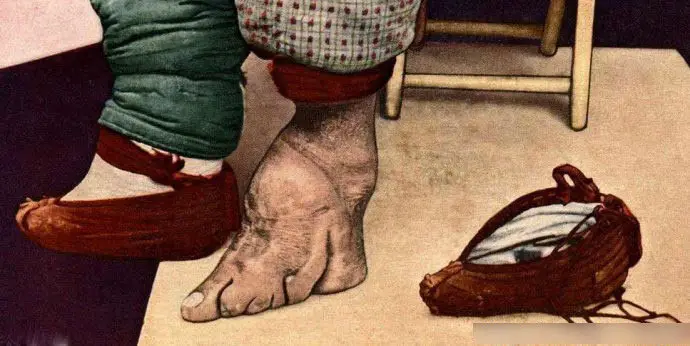

Life with Bound Feet

For women with bound feet, pain was a daily companion. Every step was a careful calculation—slow, deliberate, and often excruciating. Walking was reduced to a short, swaying gait, which was ironically considered elegant and attractive. But behind this image of grace was a reality of instability and suffering.

Simple tasks like climbing stairs, carrying water, or tending to children became difficult or impossible. Many women relied on canes or walls for support. Falls were common, especially as women aged and their bodies weakened under the strain of a lifetime spent balancing on malformed feet.

Yet life didn’t stop. Despite the pain, these women still had to manage households, raise families, and—especially in poorer communities—contribute to their survival. Their resilience was remarkable, even when their mobility was severely limited.

Marriage Prospects and Social Mobility

Marriage was one of the strongest motivations for foot binding. A well-bound foot was often a girl’s greatest asset in securing a good match. Matchmakers would inspect a girl’s feet the way a jeweler might study a gemstone—looking for symmetry, size, and shape.

In many cases, the smaller the feet, the better the chances of marrying into a wealthier or higher-status family. Foot binding was seen as a sign that a girl came from a home that valued tradition and discipline. It also suggested that she was prepared to endure hardship for the good of her future husband’s household.

Conversely, girls with unbound or poorly bound feet often faced stigma and rejection. In some regions, a girl with large, natural feet might only marry a laborer or remain unmarried. The pressure was immense—not just for the girls, but for their families.

Bound Feet and Work Limitations

Women with bound feet faced serious restrictions in physical labor. In rural areas, where women often helped with farming or manual work, this created a practical problem. Some families delayed or loosened the binding process to allow their daughters to work, then tightened it again later in hopes of salvaging marriage prospects.

In urban settings, where foot binding was most strictly observed, women were more likely to be confined to indoor roles. They might focus on embroidery, weaving, or managing the household—tasks that required skill, but not mobility.

Still, many women pushed through the pain to perform daily tasks. The myth that women with bound feet were entirely helpless is not entirely true. Many adapted, finding creative ways to balance tradition with necessity.

Stories from Women Who Lived Through It

The voices of women who lived through foot binding offer a rare and deeply human perspective. Some described the practice with sorrow and bitterness. Others, surprisingly, spoke with pride—seeing their bound feet as proof of their strength, endurance, and femininity.

In interviews conducted in the 20th century, elderly women recounted the sharp, lasting pain that never truly left them. They remembered mothers crying as they bound their feet, torn between love and social pressure. Some expressed regret, especially when they saw younger generations walk freely and go to school.

Yet others recalled how having bound feet gave them dignity within their cultural context. One woman from Yunnan province once said, “If my feet were not bound, I could not have married. And then, what kind of life would I have had?”

These testimonies highlight the emotional complexity behind foot binding. For many, it was both a burden and a badge of identity—painful, yes, but also deeply tied to their sense of womanhood in a world that offered few choices.

| Health Issue | Description |

| Bone Deformities | Curled toes, broken arches, heel displacement |

| Chronic Pain | Lifelong pain in feet, legs, and back |

| Limited Mobility | Inability to walk long distances or stand for long periods |

| Arthritis and Joint Damage | Early-onset arthritis in knees and hips due to altered gait |

| Risk of Falls | Frequent in old age due to poor balance and weakened leg muscles |

| Infections and Amputations | Common in early stages; some lost toes due to poor circulation |

Related reading: Exploring The Importance Of Family In Chinese Culture – Opens in new tab

Foot Binding – Regional Differences and Variations

Foot binding was practiced throughout much of China, but how it was performed—and how strictly it was enforced—varied significantly between urban and rural communities.

In urban centers, particularly among the elite and scholar-official families, foot binding was almost universal and often more extreme. These were the social circles where beauty, refinement, and tradition carried the most weight.

Girls from wealthy urban families were more likely to have their feet bound tightly and consistently, often achieving the smallest and most highly prized shape—the infamous three-inch golden lotus (feet no longer than 7.5 to 10 centimeters – about 3 to 4 inches). These families could afford to shelter girls from manual labor, allowing the binding process to proceed with fewer interruptions.

In contrast, rural areas showed more flexibility. While foot binding was still common, it was often done less tightly to preserve some level of mobility. Girls in farming communities were often needed to help with work in the fields, carry water, or care for animals. In some cases, binding was postponed until a girl was older, or feet were re-bound only on occasion to retain the desired shape. In the poorest households, foot binding was skipped altogether if survival demanded a strong, able-bodied woman.

Despite these differences, the cultural pressure remained. Even in rural areas, a girl with unbound feet risked social judgment and reduced marriage options.

Styles of Binding Across Dynasties and Provinces

The style and method of binding evolved across dynasties and differed based on regional customs. In the Song Dynasty, for example, the trend favored high arches and slightly curved feet—delicate, but not necessarily tiny. By the Qing Dynasty, the practice had intensified, and the most desirable bound foot was incredibly small and tightly folded, with toes crushed under the sole and the arch dramatically lifted.

Geography also played a role. In northern China, where the Han majority dominated, foot binding was more widespread and strict. But even among Han Chinese, some communities developed unique shoe styles and binding techniques, reflecting local customs and resources.

Southern provinces like Fujian and Guangdong saw a mix of Han and ethnic minority groups, some of whom resisted the practice or adapted it differently.

Among the Hakka people, for example, foot binding was uncommon or rejected entirely, as women were expected to contribute significantly to agricultural labor.

The Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty officially forbade foot binding among their own women, who instead wore distinctive “flower bowl” shoes that mimicked the swaying gait of bound feet without the painful process.

Different regions also had distinct aesthetics and naming conventions. In some places, foot shapes were compared to “willow leaves” or “bowls,” while others used poetic terms like silver lotus, fragrant petals, or tender moon. These variations reveal how deeply embedded the practice was in local culture and identity.

| Group/Region | Prevalence/Style of Binding | Notes |

| Urban Elite | Most severe, smallest feet sought | Symbol of status, little physical labor |

| Rural Families | Often looser binding or later start | Needed for work, less severe deformation |

| Central/Northern China | More common, stricter techniques | Influenced by court and elite culture |

| Southern Provinces | Less common, looser binding | Economic necessity reduced prevalence |

Resistance and Criticism Over Time

Though foot binding was deeply entrenched in Chinese society for centuries, it was never without its critics. Even during the height of its popularity, there were individuals—often scholars, poets, and some Buddhist or Taoist figures—who questioned its morality and impact.

Some early Confucian scholars argued that altering the natural body, especially in such a violent way, went against the principle of filial piety, which teaches that one should not harm the body given by one’s parents. Others lamented the suffering of girls and women, viewing the practice as cruel and unnecessary, especially when it resulted in lifelong disability.

One of the earliest forms of resistance came from the Manchu rulers during the Qing dynasty. In 1645, the first Shunzhi emperor issued a mandate banning foot binding among the conquered Han Chinese.

However, this early attempt at prohibition proved unsuccessful, as the practice was already deeply embedded in cultural traditions. The Kangxi emperor, who succeeded him, eventually revoked the ban, apparently concluding that “the practice was too firmly rooted in custom to be amenable to imperial dissolution”.

Throughout the Qing period, opposition continued to emerge, though it remained “both belated and weak”. The ruling Manchu nobility maintained their own distinct cultural practices and prohibited foot binding among their women, who instead wore distinctive “flower bowl” shoes that mimicked the swaying gait of bound feet without the painful binding process. This represented an early alternative that challenged the necessity of the practice while still acknowledging the aesthetic it created.

Still, these voices were largely drowned out by prevailing social norms and the fear of deviating from what was considered proper. For most families, opposing foot binding meant risking social ridicule or condemning a daughter to a future without marriage—an unthinkable fate at the time.

Foreign Missionaries and Western Influence

The first major external challenge to foot binding came with the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries, and more forcefully in the 19th century. These missionaries were appalled by the practice and saw it as not only barbaric but a symbol of what they viewed as China’s moral and cultural backwardness.

Missionaries often took in orphaned or abandoned girls and refused to bind their feet, raising them as part of their Christian communities. Adele M. Fielde was one such missionary who worked against the practice in the late 19th century. Many also established schools where girls were taught reading, writing, and practical skills—offering an alternative path to marriage and motherhood.

Their advocacy, while often paternalistic and culturally biased, did help spark debate within China. Pamphlets, books, and public speeches began to appear, denouncing foot binding and calling for its end. Some Westerners formed anti-foot-binding societies, which later joined forces with Chinese reformers to spread their message more widely.

Chinese Reformers and Intellectuals Speak Out

By the late 19th century, Chinese intellectuals and reformers began to oppose foot binding with increasing vigor, though their motivations were often tied more to nationalist concerns than to women’s welfare. There was “a growing self-consciousness among intellectuals about how China was perceived by the rest of the world”. Many reformers were concerned with modernization as a means of making the nation respectable on the world stage, and bound feet became a symbol of everything that held China back.

Kang Youwei (1858-1927), a prominent Chinese reformer associated with the 1898 Hundred Days Reform, was particularly influential in the anti-footbinding movement. In 1894, he founded the Anti-footbinding Society (戒缠足会; Jiè chánzú huì), which eventually gathered over ten thousand followers. In 1898, Kang submitted a petition to the throne stating that “China was seen as a joke to foreigners and… that footbinding was the primary object of such ridicule”. His arguments reflected the nationalist orientation of many Chinese reformers, who “believed that bound feet made women weak, which in turn made their offspring weak, and the nation weak by extension”.

Following the Boxer Rebellion of 1902, the Qing court itself began to support reformist plans, including the anti-footbinding movement, in an effort to strengthen the Chinese empire. In 1903, the male scholar-reformer Jin Yi published “The Women’s Tocsin (Nujie Zhong),” described as the “first systematic manifesto of women’s liberation in China”. In this work, footbinding was labeled as the first of four “cardinal harms” on women of “Old China”.

Female reformers also emerged, including pioneering educators like Qiu Jin and Ding Ling, who viewed foot binding as both a physical and psychological cage. They spoke out in newspapers, held rallies, and established schools for girls that rejected the practice entirely.

By 1908, the majority of Chinese public opinion had turned against footbinding. The practice began to decline rapidly, particularly after the 1911 fall of the Qing dynasty, as the ban against footbinding carried into the 1912 Nationalist Revolution.

However, it’s important to note that this transition was not motivated primarily by concern for women’s welfare. Rather, Chinese reformers “adopted the colonial mindset of westerners and came to equate the ‘necessary condition’ for the ‘liberation’ of their women from traditional practices such as footbinding as a ‘necessary condition’ of their own liberation”.

Though change was slow and often met with resistance—especially in rural areas—the tide was turning. What had once been a mark of honor was increasingly seen as a symbol of oppression.

Learn more: “From Tradition to Modernity: Footbinding and Its End (1839-1911)” by Saman Rejali from University of Toronto Mississauga (PDF)

| Figure/Group | Time Period | Contribution |

| Kang Youwei & Liang Qichao | Late 19th Century | Intellectuals who publicly opposed the practice |

| Christian Missionaries | 19th Century | Spread awareness abroad; provided education alternatives for girls |

| Anti-Foot Binding Societies | Early 1900s | Grassroots campaigns urging families to stop binding daughters’ feet |

| Chinese Communist Party | Post-1949 | Criminalized and strictly enforced unbinding policies |

The Decline and End of Foot Binding

Following the 1911 revolution, the Republican government officially banned foot binding again in 1912. Unlike previous attempts, this ban was part of a comprehensive modernization program backed by changing social attitudes. The Republic of China government began enforcing the ban more strictly by 1915, even “handing out fines for violations”.

Anti-foot binding campaigns during this period were remarkably effective. The movement had initially been “pioneered by the actions and discourse of foreign Christian missionaries and Chinese intellectuals who effectively extinguished the cultural prestige footbinding carried”. By the Republican era, leadership in the movement had “passed from the western missionaries to the Chinese themselves”, giving the campaigns greater cultural legitimacy and effectiveness.

These campaigns combined education, social pressure, and legal enforcement. Anti-foot binding societies encouraged people to take vows not to bind their daughters’ feet or allow their sons to marry women with bound feet. This coordinated approach proved highly effective in changing social norms around the practice.

Laws, Education, and Changing Attitudes

In the 1920s and 1930s, formal bans on foot binding were introduced in many provinces. While enforcement was inconsistent—especially in remote rural areas—these laws sent a strong message. The tide of public opinion was shifting.

Education played a powerful role. As more girls entered schools, especially in cities, they were taught about the dangers and consequences of foot binding. Teachers became some of the most influential advocates for unbound feet, presenting them as symbols of progress and patriotism.

The rise of new ideals around womanhood also helped change attitudes. Women began to participate more in public life—as students, workers, and activists. Bound feet no longer aligned with this emerging image of the modern Chinese woman.

The changing attitudes toward foot binding were dramatic and swift. Statistics from this period show that in Dingxian, an area south of Beijing where over 99% of women used to have bound feet, no new instances were discovered among those born after 1919. This remarkable shift demonstrates how quickly social norms can change when multiple factors align—in this case, legal prohibition, education, changing beauty standards, and nationalist sentiment.

Still, change did not happen overnight. Many families clung to the tradition out of habit, fear, or concern for their daughters’ marriage prospects. But each new generation saw fewer and fewer girls undergo the binding ritual.

The Last Generation: When the Practice Truly Ended

By the mid-20th century, foot binding had largely disappeared in cities. In some rural communities, however, it continued quietly into the 1940s and even the early 1950s. The final blow came after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

The new Communist government outlawed foot binding entirely and enforced the ban with unprecedented strictness. Propaganda campaigns condemned it as feudal and anti-revolutionary. Health workers traveled to villages, unwrapping bindings and inspecting feet. Women with bound feet were often encouraged—or pressured—to let their daughters walk free.

By the 1960s, it was virtually unheard of to see a young girl with bound feet. The last generation of bound-foot women grew old in silence, their small, misshapen feet a fading reminder of a world that had vanished.

Today, only a handful of elderly women with bound feet remain alive, living testimonies to a practice that spanned nearly a thousand years of Chinese history.

The elimination of foot binding represents “a rare documented success taken place at a time when Chinese society did not have all that much to celebrate”. It’s estimated that approximately 2 billion women had their feet bound over the centuries from 949 to the early 20th century.

The practice that had once seemed an immutable part of Chinese culture was effectively eliminated within a single generation, demonstrating the potential for rapid social change even for deeply entrenched cultural practices.

| Period | Event |

| 10th Century | Origins during the Song Dynasty; earliest written references appear |

| 13th–17th Century | Widespread practice across elite classes |

| Late 1800s | Western criticism begins; missionary reports raise awareness |

| Early 1900s | Republican-era reformers begin anti-foot binding campaigns |

| 1912 | Official ban after fall of Qing Dynasty |

| 1949 | Communist government enforces final outlawing |

| 1990s–2000s | Last generation of women with bound feet share their stories |

Further study:

- “The Disappearance of Foot-Binding in Tinghsien” by Sidney D. Gamble from American Journal of Sociology

- “The Influence of Western Women on the Anti-Footbinding Movement 1840-1911” by Alison R. Drucker. Published By: Berghahn Books

- “Footbinding and its cessation” by Laura Smith Chowdhury, Yile Zhang, Ryan Nichols. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2022.08.005

Long-Term Effects and Legacy

For the women who lived with bound feet, the physical consequences endured long after the bindings were removed. Decades of pressure on bones, joints, and muscles left permanent deformities. Most survivors walked with a limp or shuffle, unable to balance without aid. Many suffered from chronic pain well into old age.

Medical examinations of elderly women who had undergone foot binding revealed severe issues: broken arches, fused toes, bone spurs, and loss of circulation. Some had missing toes due to infections that had gone untreated in childhood. Arthritis was common. In later years, limited mobility contributed to higher risks of falls and fractures.

The feet were not the only part of the body affected. The strain placed on knees, hips, and the lower back altered the way women stood and walked, leading to complications in posture and internal organ alignment. Even after unbinding, the body could not revert to its natural state.

Psychological and Emotional Impact

The emotional scars of foot binding were just as real as the physical ones. For many women, the memories of pain, shame, and pressure lingered for a lifetime. Binding often began between the ages of four and seven—an age when most children should be playing, not enduring daily agony. These early experiences left deep impressions.

Some women later expressed feelings of betrayal, recalling how mothers or grandmothers—often the ones who performed the binding—inflicted the pain out of love and duty. Others were haunted by memories of isolation, teasing, or the fear of being unmarriageable if the binding was not done properly.

Yet, for some, the practice was a source of conflicted pride. Bound feet had once secured their place in society, won them husbands, and preserved family honor. In later years, these women often felt left behind by a world that had suddenly labeled them as victims or relics. It was a confusing and sometimes painful transition.

The psychological legacy of foot binding also created a silence around the topic. Many women were reluctant to speak about their feet or show them, even to doctors. The trauma became internalized, tucked away behind modesty and endurance.

Cultural Memory and Identity

Today, foot binding occupies a complicated space in Chinese cultural memory. It is remembered as both a tragedy and a tradition—a symbol of suffering, but also of endurance and strength. For many, it represents the extremes women were pushed to for the sake of beauty and social acceptance.

Museums across China now preserve shoes, photographs, and tools used in the practice. Oral history projects have documented testimonies from elderly women, helping to ensure their voices are not lost. These efforts reflect a growing interest in understanding, not just condemning, the practice.

Within Chinese identity, foot binding is often seen as a painful chapter of history—one that invites reflection rather than judgment. It raises essential questions: What is the cost of conforming to societal ideals? How do we balance tradition with human dignity? And how can we honor those who suffered without romanticizing the past?

Modern Chinese women, many of whom are just one or two generations removed from bound-foot grandmothers, carry this legacy with them. Some feel a sense of sorrow, others curiosity, and still others—especially artists, writers, and scholars—seek to explore the deeper meanings hidden in this once-private world.

Foot binding is no longer a living tradition, but its imprint remains—in family stories, cultural discourse, and the collective memory of a nation still reckoning with its past.

Further reading: Qin L, Pan Y, Zhang M, et al. “Lifelong bound feet in China: a quantitative ultrasound and lifestyle questionnaire study in postmenopausal women.” BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006521. Published 2015 Mar 17. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006521

Preservation and Education

Although foot binding has long been outlawed, its history is preserved through museums and cultural institutions across China and beyond. These spaces serve as both educational centers and memorials—dedicated to remembering a tradition that shaped generations of women.

The Chinese Foot-binding Culture Museum in Wuzhen (Three-inch Golden Lotus Shoes Museum, 三寸金莲博物馆) and Jianchuan Museum ( 建川博物馆传承) are a prominent examples, offering an objective and detailed display of the history, artifacts, and cultural significance of bound and unbound feet. Through carefully curated exhibits, visitors can see the tiny, elaborately embroidered shoes, binding cloths, and personal items used by women, bringing the realities of this tradition to life.

Internationally, museums such as the British Museum and New York’s Museum of Chinese in America have featured exhibits on foot binding within broader discussions of gender, culture, and tradition. These global displays help inform the world about the practice beyond stereotypes, offering a more nuanced perspective rooted in historical and cultural context.

These museums serve as educational spaces, ensuring that the painful legacy of foot binding is not forgotten and that future generations can learn from this chapter of history. Traveling exhibitions, such as “Bound to Be Beautiful: Foot Binding in Ancient China,” have also brought these stories and artifacts to international audiences, showcasing the artistry and suffering intertwined in this practice.

Oral Histories and Testimonies from Survivors

The voices of surviving women with bound feet are essential for understanding the lived experience behind the tradition. Oral histories and personal testimonies have been collected by journalists, authors, and researchers, capturing the pain, pride, and regret felt by these women.

Survivors like Wang Lifen and Zhou Guizhen have shared their stories—describing the rituals, the family pressures, and the lifelong consequences of bound feet. Their accounts reveal the complexity of their feelings: some recall the pride of fitting into the smallest shoes, while others express deep regret at the loss of mobility and freedom.

Books such as Splendid Slippers by Beverley Jackson and Every Step a Lotus by Dorothy Ko (Aff.links) have helped bring these voices to a global audience. These stories give texture to the history—offering insights into the emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions that textbooks often overlook.

As many of these women have now passed away, the preservation of their testimonies ensures their stories remain part of the historical record. They are not just statistics; they are names, faces, memories, and reflections.

More books on this topic (Aff.links):

- “Chinese footbinding: The history of a curious erotic custom” by Howard S Levy

- “Cinderella’s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding” by Dorothy Ko

- “Bound Feet, Young Hands: Tracking the Demise of Footbinding in Village China” by Laurel Bossen & Hill Gates

- “Footbinding as Fashion: Ethnicity, Labor, and Status in Traditional China” by John Robert Shepherd

Final Thoughts

The story of foot binding is one of complexity—woven with pain, endurance, and the quiet strength of generations of women. For nearly a thousand years, this practice shaped the lives of millions, leaving both visible and invisible marks on their bodies, minds, and the course of Chinese history.

It’s easy to view foot binding as a cruel and outdated custom, but its persistence reveals how deeply beauty standards and social expectations can become embedded in a culture. Families believed they were securing a better future for their daughters, even as they inflicted suffering. Women endured the pain with dignity because their identity, value, and chances at a respectable life depended on it. Understanding this complexity allows us to view the past not just through the lens of condemnation, but with compassion and insight.

This history offers us powerful lessons. It urges us to reflect on the sacrifices people—especially women—have made to meet the ideals of their time. It forces us to consider the ways in which harmful traditions are passed down through love, duty, and fear. And it reminds us that social change, though slow and painful, is possible through awareness, education, and collective action.

Although foot binding officially ended decades ago, its echoes are still felt. Modern societies around the world continue to pressure women into conforming to often unrealistic standards of beauty and behavior. The tools may have changed, but the patterns remain. High heels, body-shaping garments, cosmetic procedures—these too reflect society’s ongoing effort to mold women’s bodies into ideals.

Foot binding is no longer practiced, but it continues to resonate because it speaks to a timeless truth: the cost of acceptance can be unthinkably high. By remembering and studying this tradition, we not only honor those who endured it, but we also gain the insight needed to challenge and rethink our own norms today.

Related reading: The Most Powerful Women in Ancient China – Opens in new tab

Further study:

- J Mao. “Foot Binding: Beauty And Torture.” The Internet Journal of Biological Anthropology. 2007 Volume 1 Number 2. DOI: 10.5580/11bb

- “Love and Labor: Footbinding in Rural China in the Twentieth Century” by Meghann Burgess from Bridgewater College

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured image from Foot Binding Museum Wuzhen