Long before silicon chips and smartphones reshaped the way we think about numbers, civilizations across the globe relied on tactile, analog devices to perform complex calculations. Among these, the Chinese abacus, or suànpán, stands out not only as a brilliant example of ancient innovation but as a symbol of China’s enduring intellectual tradition.

Originating more than 700 years ago, the suànpán did more than crunch numbers—it trained minds, supported empires, and influenced cultures from East Asia to Europe. Though deceptively simple in structure—just beads and a wooden frame—the abacus embodies profound layers of symbolism, history, and educational philosophy.

This article explores the origins, functions, symbolic meanings, and lasting cultural impact of the Chinese abacus, revealing how a humble counting tool became a timeless icon of wisdom and ingenuity.

The Origins of Abacus – Suànpán (算盘)

While the Chinese suànpán (算盘) as we know it became standardized around the 14th century A.D. during the Yuan Dynasty, the roots of abacus-like devices in China reach far deeper into antiquity. Evidence suggests that the earliest forms of counting tools in China can be traced back more than 2,000 years, possibly even as far as the Warring States Period (475–221 BCE).

These early devices were not suànpán in the strict sense but were likely counting boards or knotted cords (known as jiǎnshù 简数) used to keep track of tallies. The use of bamboo rods and small pebbles arranged on lines scratched into boards may have prefigured later bead-frame structures. Some Chinese historians argue that these were early adaptations of a positional notation system, which provided a visual and tactile way to perform arithmetic, laying the groundwork for the logic behind the abacus.

The first recorded reference to a counting frame in China appears in texts from the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE). In the mathematical treatise Zhoubi Suanjing (周髀算经) and later The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (九章算术), scholars describe computational techniques that strongly suggest the use of organized counters or proto-abaci.

While no physical devices have survived from this period, their mathematical practices were complex and precise, involving fractions, equations, and geometric principles, all of which would have benefited from physical counting tools.

By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the concept of a bead-based counting tool had matured considerably. Historical records such as those from scholar and mathematician Lu Juyan (陆居人) mention tools that resemble the suànpán. These accounts show that the Chinese were developing increasingly refined tools to assist with commerce, land measurement, taxation, and engineering—all of which demanded advanced calculation methods.

It’s also important to note that the development of the abacus in China was independent of similar devices in Babylon, Greece, and Rome. This parallel evolution speaks to the universality of mathematical need across cultures, but China’s version would become uniquely versatile due to its capacity to operate not only in base-10 but also in base-16, which aligned with traditional units of weight and currency like the tael (两).

Thus, the suànpán did not appear suddenly but was the result of centuries of mathematical evolution, driven by both intellectual curiosity and practical necessity. Its emergence was not merely a technological leap but a cultural milestone that reflected China’s long-standing reverence for order, calculation, and balance.

Timeline of the Abacus Across Cultures

| Year/Period | Region | Development/Event |

| c. 200 BCE | Mesopotamia | Early counting boards emerge |

| 14th Century | China | Suànpán becomes standardized in design |

| 1600s | Japan | Abacus introduced from China |

| 1800s | Japan | Soroban standardized during Meiji reforms |

| 1400s | Korea | Adapted abacus known as jupan or jusan |

| 2013 | Global (UNESCO) | Suànpán recognized as Intangible Cultural Heritage |

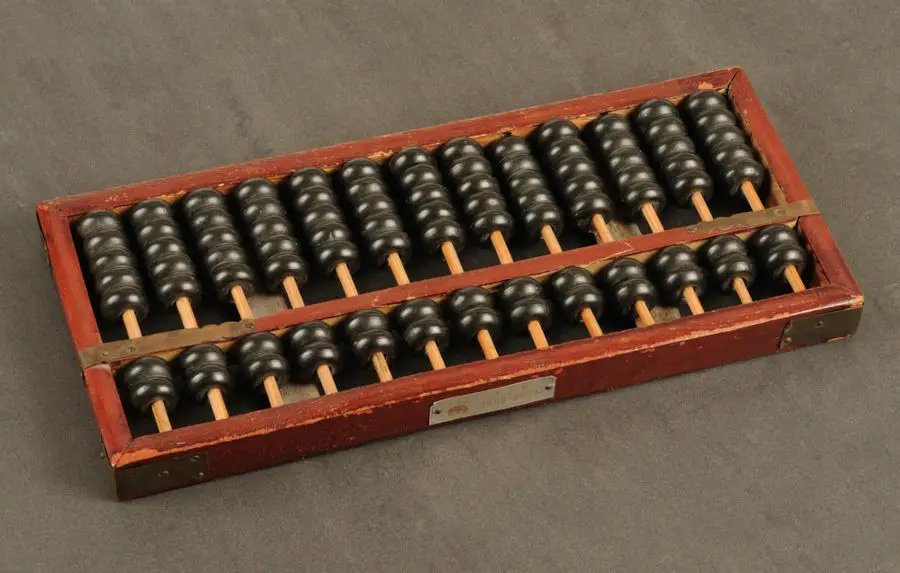

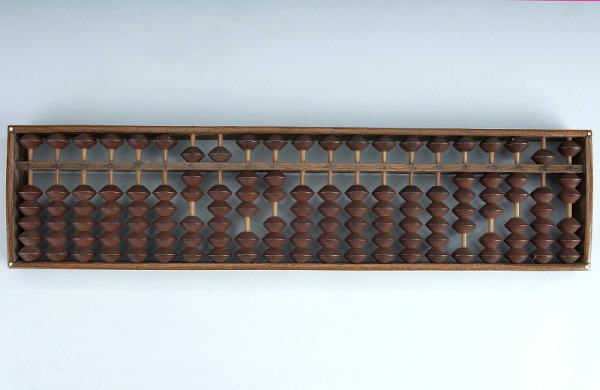

Symbolism in the Design

The structure of the Chinese abacus, or suànpán, is not merely practical—it is deeply symbolic, reflecting fundamental principles of Chinese cosmology, philosophy, and metaphysics. The division of the abacus into two decks—the upper deck with two beads and the lower deck with five—corresponds to the ancient Chinese concepts of Heaven (天, tiān) and Earth (地, dì), respectively. This Heaven-Earth duality is central to Daoist and Confucian worldviews, both of which emphasize harmony, balance, and the interaction of opposites.

In traditional Chinese thought, Heaven governs the immaterial, the ideal, and the universal, while Earth represents the material, the practical, and the specific. On the suànpán, the upper beads (Heavenly beads) are worth five units each, while the lower beads (Earth beads) are worth one unit each. This 5:1 ratio may reflect the Yin-Yang principle—the balance between dual forces—and the numerical harmony often emphasized in I Ching (易经) philosophy, where numbers are not just quantitative but also symbolic of cosmic forces.

Furthermore, the total of seven beads per rod (two above, five below) has symbolic significance as well. In Daoist tradition, the number seven can represent the union of Heaven (3) and Earth (4)—3 being a celestial number (as in the three realms: Heaven, Earth, and Humanity) and 4 representing the earthly directions (north, south, east, west). Their combination into seven signifies a wholeness or completeness that aligns with the suànpán’s use as a tool for ordering and balancing numbers.

The horizontal bar, which separates the two sections, can be seen as the axis or threshold—a liminal space that allows Heaven and Earth to communicate. In this way, each calculation is not just a mechanical process but a symbolic act of bringing order to chaos, of mediating between abstract values and practical applications.

There’s also a cultural layer to the materials traditionally used. The wooden frame represents natural growth and integrity, and jade or ivory beads, in more luxurious versions, indicated status and refinement. The sound of beads striking the frame was described in historical texts as calming and rhythmic, not unlike a chant, which helped merchants and scholars maintain mental focus—an echo of the Confucian ideal of disciplined study and internal harmony.

Thus, using the abacus was more than computation—it was a ritualistic act, a meditation on balance and logic, and a physical expression of centuries-old Chinese values. In classrooms and market stalls alike, the suànpán carried this philosophical weight, blending the practical with the spiritual in a uniquely Chinese way.

Educational Significance and Mental Abacus Training

The Chinese abacus, or suànpán, has played a significant role not just in commerce and accounting, but also in education, especially in training mental arithmetic skills. Over centuries, it became a vital tool in developing not only mathematical proficiency but also discipline, memory, and concentration—traits deeply valued in traditional Chinese pedagogy.

Historical Use in Chinese Education

From the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) onward, the abacus began to be systematically incorporated into formal education. Private tutors, Confucian academies, and merchant schools used the suànpán to teach basic numeracy, business mathematics, and even moral habits, such as patience and accuracy.

It was believed that mastering the abacus could help cultivate a sharper mind and a more orderly way of thinking. The phrase “算盘打得精” (suanpan da de jing, “having a sharp abacus”) came to mean someone who is clever and economically shrewd—showing how deeply the tool was woven into Chinese cultural and intellectual life.

Mental Abacus: Anzan and Visualization Training

In more recent decades, the concept of mental abacus training, where individuals visualize an abacus in their mind and manipulate beads mentally to perform arithmetic, has gained international attention. This practice is especially prominent in China, Japan (where it is called anzan), and Korea. After years of physical training on the abacus, students gradually transition to using an “imaginary abacus” to perform complex calculations without any device at all.

Neurological studies, including MRI scans, have shown that abacus-trained children use visual-spatial pathways in the brain more intensively than those who use only modern calculators. This has led researchers to suggest that mental abacus users are essentially “seeing” the beads move during calculations, which engages the brain holistically, combining numerical, visual, and motor-processing areas.

Benefits of Abacus Training

Modern educational research has demonstrated a range of cognitive benefits associated with abacus-based mental math training:

- Improved working memory: The need to hold multiple numbers and positions in mind strengthens short-term and long-term memory.

- Enhanced concentration and attention span: Students must stay mentally engaged to accurately visualize and manipulate bead positions.

- Accelerated calculation speed and accuracy: With practice, mental abacus users often outperform peers using electronic calculators.

- Better numerical sense and mental flexibility: Children learn to break down numbers into parts and develop intuitive number manipulation strategies.

- Cross-disciplinary thinking: The pattern recognition and logic required in abacus training support skills used in music, coding, and spatial reasoning.

Global Integration in Education

Outside Asia, mental abacus programs have been adopted in countries like India, Malaysia, and even the United States through after-school programs and math enrichment academies. International competitions such as the Mental Arithmetic World Cup and the UCMAS International Abacus and Mental Arithmetic Competition have spotlighted young prodigies who can solve multiple-digit arithmetic problems in mere seconds—entirely in their minds.

In some Chinese primary schools today, particularly in regions with strong traditional roots, the abacus is still part of the curriculum, both as a way to connect students with their heritage and as a proven tool to enhance early numeracy. Teachers often note that students who learn the abacus show a deeper understanding of mathematical operations and greater confidence in problem-solving.

Related reading: Innovation Through the Ages: Unraveling the Timeline of Chinese Inventions – Opens in new tab

The Chinese Abacus vs. Japanese Soroban

The Chinese abacus (算盘, suànpán) and the Japanese soroban (そろばん) share a common heritage but have evolved into distinct tools, reflecting not only technical differences but also cultural adaptations in approach to mathematics and education.

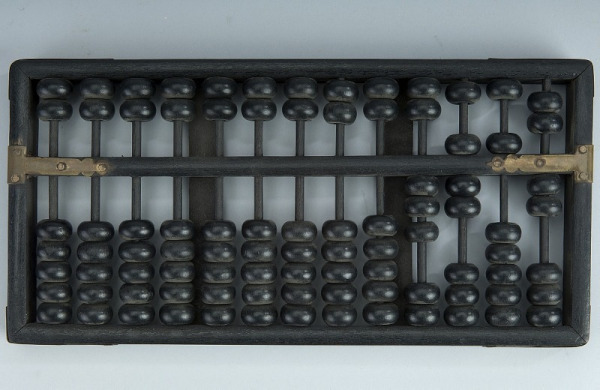

Structural Differences

The most immediately noticeable distinction lies in the bead configuration:

- Suànpán: Typically features two beads on the upper deck (heaven beads) and five beads on the lower deck (earth beads) per rod. This 2:5 arrangement supports both decimal and hexadecimal systems, which was practical in historical Chinese contexts involving weights, currency units, and traditional measurements.

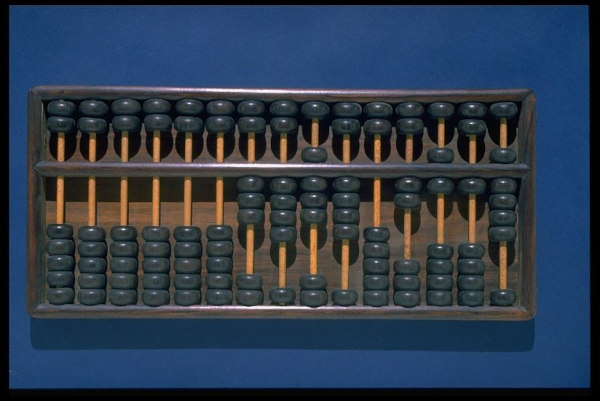

- Soroban: Modern versions feature one bead above and four below (1:4 configuration). This simplified format, standardized in the 19th century Meiji era, is optimized for the decimal system and aligns with Japan’s shift to Westernized metric standards and modern accounting practices.

This reduction in bead count made the soroban faster and more efficient, especially for addition, subtraction, and multiplication—key functions in modern commerce and education. The Japanese soroban also tends to be more compact and standardized in size (typically with 13, 17, or 23 rods), making it more portable and uniform for widespread classroom use.

Philosophical and Practical Evolution

The Chinese suànpán, rooted in the dynastic periods of commerce, taxation, and scholarly examination, was a flexible instrument designed to handle diverse units of measurement. It reflects traditional Chinese adaptability, capable of handling multiple numerical bases, including base-16 used for weight and monetary calculations (e.g., 16 taels in one jin).

In contrast, the Japanese soroban embodies simplicity, precision, and efficiency, which became hallmarks of Japanese educational philosophy during modernization. It represents a transition from traditional to industrial thinking—streamlined, efficient, and aligned with international systems.

The shift from the 2:5 configuration of the Chinese abacus to the 1:4 layout of the soroban was not just about ease of use, but also about pedagogical refinement. The fewer beads reduced ambiguity in interpretation and reinforced decimal understanding, making it more intuitive for young learners.

Educational Use and Standardization

In China, while the abacus was widely used in traditional education and remains a respected cultural tool, its usage has gradually declined in formal schooling, especially after the rise of electronic calculators. However, in Japan, the soroban remains an integral part of early math education and is often taught alongside modern arithmetic methods.

Japanese students undergo national certification exams in soroban proficiency, and soroban schools (soroban juku) remain popular extracurricular institutions. The practice of anzan (mental abacus visualization) is also a prominent feature of Japanese abacus education, where students visualize the soroban to perform calculations mentally—a practice that is exported globally.

Legacy and Global Influence

The soroban has had a more prominent influence on global mental math programs, especially those adopted in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Many international math training centers use modified soroban models and techniques due to their clarity and effectiveness in teaching young learners.

Meanwhile, the suànpán remains a symbol of traditional Chinese ingenuity and cultural pride. It continues to be used in folk crafts, historical reenactments, and museum exhibits, and is increasingly being reintroduced in Chinese schools as a heritage education tool, especially in provinces seeking to preserve local traditions.

| Feature | Chinese Abacus (Suànpán) | Japanese Soroban |

| Upper Deck (Heaven Beads) | 2 beads | 1 bead |

| Lower Deck (Earth Beads) | 5 beads | 4 beads |

| Number System | Decimal + Hexadecimal (Base-10 & Base-16) | Decimal only (Base-10) |

| Typical Use | Traditional calculations, commerce, weights | Educational arithmetic, mental math |

| Size | Varies; often larger | Standardized, more compact |

| Era of Modern Standardization | 14th century | Meiji era (19th century) |

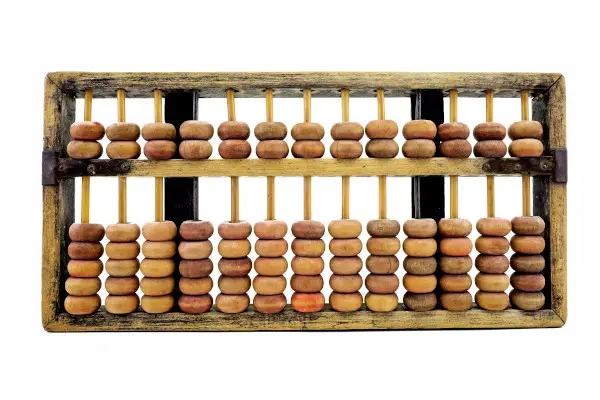

What is an abacus actually made of?

This form of computing device was created using wood and beads. Since the Chinese abacus was very handy, it was no surprise that it was successfully proliferated in other countries ever since they learn the power of the tool which was made out of simple yet very effective in doing arithmetic processes.

More so in resetting the tool, the abacist or the abacus user executes a quick shaking of the suànpán along the horizontal axis to move all the beads away from the center of the horizontal beam.

The truth is, suànpán was built to handle operations like division, addition, multiplication, subtraction, and even square root and cube root. This shows the concept that a simple idea can manifest complexities in its usage. Though it can not do what calculators do, it can serve its purpose in many ways like accounting for animals they killed and recording and storing details they gathered in computing.

Take a look at these awesome Abacus designs.– Aff,link

How to Use an Abacus

Modern people are still fascinated with the idea that abacus can truly perform mathematical computations given the simple way it was created and the simple rationale behind its existence. Nonetheless, the simplicity of the idea of an abacus goes against the complexities it can execute.

Though you can picture in your mind what an abacus looks like and how it works, the image you created, however, is already influenced by the fact that it is just an ordinary tool in computing when sometimes it’s not actually the case.

Abacuses are still used in other Asian countries like China and Japan despite the advent of more powerful calculators. The Chinese, however, are often recognized as the inventors and pioneers of the abacus, and such a claim credited to the abacus is the earliest calculating machine in the world. Given these facts, people couldn’t help themselves to learn how to use an abacus.

Mathematical calculations using abacus have representations that will help the user do the computation. Beads represent quantity while the beads’ position represents value. When you get an abacus you will notice that it is divided into two parts. Given an abacus with 13 rows of which there are five beads, then, the lower part contains four beads while the upper part has only one bead.

The first step: move all the beads to the bottom of the abacus by slanting it causing the beads to fall to the bottom. You will know that you did the proper thing when your abacus’ section which has five beads in every row is at the bottom section over the section that has one bead in each row. Now let us mark eight ones by pushing the upper section from the furthest right row or the one’s row and then position the three earth beads at the same row.

On the other hand, marking two tens would be done by pushing two earth beads from the next row or the ten’s row. Then, in marking hundreds, the heavenly part should be pushed to the third row or the hundred’s row and three earth beads to the similar row.

Moving on, the second number which is 25 should be added. The second number was computed by the two tens and then added with the 5 ones which were the remains on the second row of the heaven part. This number will be then split into 5 ones of different values. This brief example is just one method of using an abacus.

In using abacus the values of tens, ones, and hundreds are utilized for easy reference. You should remember that an abacus is a tool that challenges visualization in adding or subtracting and multiplying or dividing. The position and the value of each row may vary to meet the bigger numbers that the user will be dealing with.

Computing simple arithmetic with bigger values highlighted the reason behind the invention of the abacus. And to add more drama about abacus as you used it, try to remember that you are using a two-thousand-year-old computation tradition.

Take a look at these awesome Abacus designs.– Aff,link

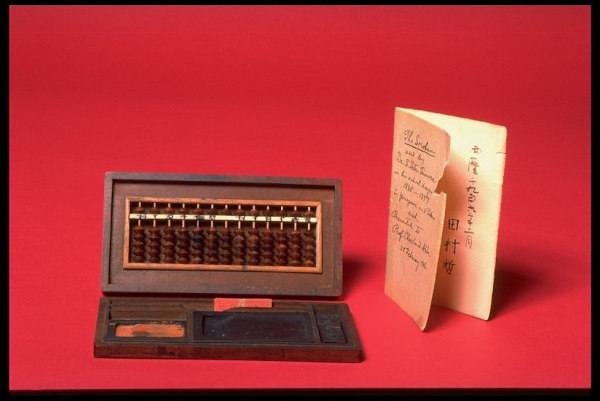

Cultural Legacy and Modern Recognition

The Chinese abacus, or suànpán, is far more than a historical calculating tool—it is a living symbol of China’s intellectual heritage, ingenuity, and lasting contributions to world mathematics. Its enduring cultural significance lies not only in its practical utility over centuries but also in how it embodies the Chinese worldview of harmony, structure, and human mastery over complexity.

A Symbol of Ingenuity and Commerce

For generations, the abacus was an emblem of commerce, learning, and problem-solving in China. Merchants, scholars, and civil officials were all trained in its use, and proficiency with the suànpán was often associated with intelligence and capability. Phrases like “算盘打得精” (“to have a sharp abacus”) remain in everyday language today, meaning someone is astute or financially savvy.

In visual culture, the abacus frequently appears in Chinese paintings, calligraphy, and period dramas, often symbolizing diligence, wisdom, and the elegance of mental discipline. It has also become a folk symbol of prosperity and good fortune. In feng shui practices, miniature golden abacuses are used as charms in offices or wallets to attract wealth and business success.

UNESCO Recognition and Global Awareness

In a landmark moment, the Chinese abacus and its associated knowledge were inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013. This official recognition by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization was a tribute not just to the tool itself, but to the generations of knowledge transmission, craftsmanship, and cultural memory it represents.

According to UNESCO’s documentation, the abacus remains a dynamic form of heritage because:

- It is still taught in some schools and used in traditional Chinese communities.

- It promotes mental calculation skills and cognitive development.

- It continues to be a source of cultural identity, particularly in regions with historical trade networks like Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong.

The inscription helped revitalize public interest in the abacus, encouraging museums, schools, and cultural institutions across China to reintroduce suànpán training, both as a mathematical tool and a gateway into traditional Chinese thought.

The Abacus in Contemporary Art and Design

Modern artists and designers have also drawn inspiration from the abacus. Contemporary art installations have used enlarged bead frames as metaphors for data, memory, and human interaction. Fashion designers, sculptors, and even architects have incorporated the abacus motif into their work to comment on themes of order, calculation, and balance in modern life.

For example, abacus-inspired public sculptures have been installed in financial districts in cities like Shanghai and Hong Kong, reflecting a modern reinterpretation of ancient tools in spaces of global finance. In educational technology, digital apps simulate the feel of a physical suànpán, allowing users worldwide to connect with Chinese mathematical heritage through touchscreens and gamified learning.

Bridging Past and Future

Today, the suànpán stands as a bridge between China’s ancient wisdom and the needs of a data-driven future. While digital calculators and computers dominate contemporary life, the abacus endures as a tool that nurtures mental discipline, numerical intuition, and cultural continuity.

As China continues to emphasize cultural confidence (文化自信) in its national development narrative, the abacus is celebrated not just as a relic, but as a timeless reminder that complexity can be mastered through simplicity, patience, and structure—values that resonate across generations and borders.

End Words

From bustling merchant stalls in ancient markets to modern classrooms cultivating mental arithmetic, the Chinese abacus continues to bridge past and present. Its legacy lives on not only in historical recognition and cultural symbolism but in the minds of those who still train with its beads—physically or mentally. Far more than a calculator, the suànpán reflects the heart of Chinese philosophy: balance, order, and the power of human reasoning. In honoring this ancient tool, we celebrate a tradition that reminds us that simplicity, when rooted in insight, can yield profound and lasting complexity.

Take a look at these awesome Abacus designs.– Aff,link

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Feature Image from Depositphotos