For over three thousand years, the ancient Chinese practice of Feng Shui—literally translated as “Wind and Water”—has shaped how generations have lived, built, worshipped, and honored their dead. Often misunderstood in the West as mere interior design or superstition, Feng Shui is in fact a deeply philosophical and environmental system that reflects China’s evolving relationship with cosmology, geography, politics, and metaphysics.

To understand Feng Shui is to understand how the Chinese perceived the world: not as a static physical space, but as a living field of energy (qi) where humans, nature, and the heavens interact. Over millennia, dynasties rose and fell, capitals shifted, empires expanded and collapsed—yet the principles of Feng Shui persisted, transformed, and reemerged, adapting to new intellectual currents, political ideologies, and religious influences.

This article traces the chronological development of Feng Shui alongside the unfolding of Chinese history, from its Neolithic roots and early divinatory practices through its refinement during imperial times, its suppression in the Republican and Maoist eras, and its remarkable global resurgence in the digital age. Each dynasty left its mark—some deepening the tradition, others attempting to erase it—yet together they tell the story of an idea that has outlived emperors, wars, revolutions, and borders.

Join us as we explore how the landscape of belief shaped the belief in the landscape, and how Feng Shui remains one of the most enduring legacies of Chinese civilization.

Feng Shui Development Across Dynasties

| Dynasty / Period | Years | Key Feng Shui Developments | Notable Contributions / Texts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Qin | < 221 BCE | Xiangdi, Zhan Bu divination, I Ching study begins | Integration of Five Elements, Yin/Yang, Bagua |

| Qin Dynasty | 221–207 BCE | Dimai (earth veins), ritual burial practices | Directional symbolism in burials |

| Han Dynasty | 206 BCE–220 CE | Kanya (Heaven-Earth-Human), Dragon Veins, early maps | Detailed terrain study |

| Tang Dynasty | 618–907 | Integration with Buddhism & Daoism, Water Dragon Classic | Feng Shui texts formalized |

| Song Dynasty | 960–1279 | Compass & Form Schools emerge, Luo Pan use expands | Yang Yun Sung’s teachings refined by Wang Chih |

| Ming & Qing Dynasties | 1368–1911 | Popularization, Flying Star, Ba Zhai methods developed | Court architecture aligned with geomantic principles |

| Republican Era | 1912–1949 | Suppressed as superstition, diaspora to SE Asia & Hong Kong | Early ethnographic studies by Chinese scholars |

| Maoist Period | 1949–1976 | Largely suppressed during Cultural Revolution | Feng Shui survives underground and in rural areas |

| Post-Reform Era | 1980s–present | Urban Feng Shui resurgence, academic research, corporate use | Government buildings quietly adjusted for Feng Shui |

| Digital Age | 2000s–present | AI, virtual Feng Shui apps, digital compass tools | Feng Shui enters metaverse and AR/VR applications |

Pre Qin Era

Before the “Qin Dynasty”, the ancient art of Feng Shui was then known as “Xiangdi” (meaning the observation and appraisal of the earth).

This helped the Chinese to select correct settlement sites, temple sites, locations for shrines and indeed the location of fertile lands. It is from this period of time that the basic principles of Feng Shui were postulated.

The choice of where to site buildings was influenced by the location of local rivers, the buildings themselves were built on high ground or raised platforms.

They were oriented in a North/South fashion with the back of the house facing North which usually afforded protection from the cold northerly winds (by a mountain, a hill or some trees).

Also during this time (during the Zhou Dynasty – 11th Century B.C. to 246 B.C.), a system of divination known as ‘Zhan Bu’ was used to determine the auspiciousness of a settlement site. From 475 to 221 B.C., the I Ching was studied in detail by ‘feng shui experts’ and it’s influence brought to bear.

In addition to the influence of the I Ching, Taoism and Confucianism started to meld with Feng Shui theories and the principles of the Five Elements, Yin/Yang and the trigrams of the Bagua were assimilated as well. (Related article: “Understanding Feng Shui In a Few Words”)

Feng Shui and Burial Practices of Neolithic China

While the Pre-Qin period laid the textual and philosophical foundations of what would become known as Feng Shui, archaeological findings suggest that the roots of geomantic thinking extend even further back—into China’s Neolithic cultures. Long before the written codification of principles such as Yin and Yang or the Five Elements, early Chinese communities were already practicing spatial awareness deeply aligned with nature.

Excavations at sites associated with the Yangshao culture (circa 5000–3000 BCE) and the later Longshan culture (circa 3000–1900 BCE) reveal early burial mounds and domestic structures carefully placed in relation to topographical features. Tombs were frequently found with entrances facing south, ensuring warmth and light—an early echo of the orientation principles found in classical Feng Shui. Similarly, settlements were often located with natural protection at the rear—hills or forests serving as the early equivalents of the later conceptual “Black Tortoise” (玄武).

Graves were not randomly oriented; rather, they reflected a nascent understanding of cosmic harmony and environmental interaction. Archaeologists have observed that these Neolithic burial practices showed a reverence for “Heaven’s order”—a cosmic hierarchy that early communities intuitively obeyed. In many cases, burial clusters appear to follow clan-based lineage orientation, suggesting that even in prehistoric times, geomantic thinking was linked not just to space, but also to ancestry and spiritual continuity.

Furthermore, these burial customs suggest a practical and spiritual symbiosis with the land—fertility, flow of water, and the health of the living were all perceived as being affected by how and where the dead were placed. The placement of tombs near flowing water but elevated from flood plains indicates an early integration of environmental sensitivity with ritual practice.

Though we have no written texts from these Neolithic peoples, their actions imply that the core idea of Feng Shui—the interaction between Heaven, Earth, and Man—was already in motion. What later became a formalized system in the Zhou and Qin dynasties began here as a living, intuitive practice that helped shape the spiritual and physical geography of early Chinese civilization.

Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC)

The Qin Dynasty (221- 207 B.C.) heralded the study of ‘Dimai’ (this is the concept of the arteries and veins of the earth – which means the study of the ridges and valleys of mountain ranges) by the ancient geographers.

During this time some of the most massive building projects of mankind were undertaken (such as the Great Wall of China and various palaces). It was during this time that the people of In developed the ritual of burial and selected sites for their ancestors based on auspicious criteria. The dead were buried, their heads facing west and the grave itself facing east.

One theory puts forth the idea that this was because the Qin Dynasty tended to spread eastwards to the coast and hence they buried their dead pointing in the direction of their ancestral homeland as a mark of respect.

Additionally, at the Yin/Yang level, east represents the newborn (Yang) energy and the west represents older life (Yin) and move towards the next world.

The living is related to the North/South orientation, hence an auspicious location for a bed is facing north (toward the north pole). The converse is true if you live south of the equator (i.e. the bed should face toward the south pole).

The Yin/Yang theory of burial site alignment holds more sway with myself as a dynasty although important is of a transient nature whereas Yin/Yang is eternal and therefore of eternal significance.

Want to learn more about Feng Shui? Take a look at these Courses and Books – Aff.link

The Western Han & the Xin Dynasties

During the Western Han (206 B.C. – 9 A.D.) and Xin (9 – 24 A.D.) dynasties, the combined study of geography and astrology – known as the study of heaven and earth in relationship to man – began.

This study was also known as ‘Kanya’. More and more detailed study of the Chinese mountain ranges was undertaken and this is where the term ‘Dragon Veins’ was born. Detailed maps and drawings of peaks, ridges, valleys, and rivers were constructed.

The Eastern Han Dynasty

During the Eastern Han Dynasty (25- 220 A.D.), many techniques and customs were developed and passed on from one Feng Shui master to the next. It was during this period of time that the roots of Feng Shui really took hold.

Cornerstone ideas such as burial site placement and living accommodation sited for maximum family prosperity were further elaborated upon (such as the notion that a good housing site was backed by mountains, close to a stream had an open vista to the front and also contained trees in the surrounding area.).

The Three Kingdoms Period And The Southern Dynasty

The Three Kingdoms period spans 220 – 280 A.D. This is comprised of the

- The Wei (220 – 265A.D.) period

- The Shu (221 – 263A.D.) period and

- The Wu (222 – 280A.D.) period

As can be seen from the dates above, these periods overlapped in time due to the differing and disparate reigns. During this time, the ‘Shui Jing’ (Book on water) was written.

The Southern Dynasty

The Southern Dynasty (420 – 589 A.D.) was also concerned with burial sites and the associated rituals. During this period, the ‘Shui Jing’ was further added to including more details on the many waterways of China, providing a vast array of information for Feng Shui masters on the harmony between the land and the buildings built thereupon.

Related reading: “Chinese Good Luck Charms To Bring Good Fortune” –Opens in new tab

Sui Dynasty (581–618 A.D.)

The Sui Dynasty, though brief, played a crucial transitional role in Chinese history and in the development of Feng Shui. After centuries of political fragmentation during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the Sui reunified China and laid the administrative and cultural groundwork for the Tang Dynasty, which would soon bring Feng Shui into a golden era.

During the Sui period, state-sponsored infrastructure projects such as the Grand Canal dramatically reshaped the Chinese landscape. These large-scale water management systems—connecting north and south—demonstrated a practical application of environmental harmonization, a core tenet of Feng Shui. While these were primarily engineering feats, they also reflected the ancient geomantic understanding of water as a carrier of qi (vital energy), influencing settlement prosperity and military logistics.

Additionally, the reunification of China under Sui rule allowed for greater standardization of scholarly knowledge, including Daoist cosmology and early geomantic texts. While there is limited surviving documentation on Sui-specific Feng Shui practices, historical evidence suggests that this was a period when geomantic expertise began to reassert its influence at the court and among elite families, especially in tomb design and city planning.

The Sui Dynasty also helped revive Confucian and Daoist learning, encouraging the preservation of earlier Feng Shui texts and preparing the intellectual climate for the explosive growth of geomantic theory during the Tang Dynasty.

Tang Dynasty (618–907)

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.) marked one of the most vibrant cultural and spiritual periods in Chinese history, and its influence on the development of Feng Shui was profound. During this golden era, Buddhism flourished alongside the native traditions of Taoism and Confucianism, creating a rich intellectual environment where metaphysical ideas could intermingle and evolve. Feng Shui, far from being isolated, absorbed and integrated elements from these diverse streams of thought.

Buddhist principles, especially those concerning the interconnectedness of all things and the concept of karma, influenced Feng Shui’s evolving understanding of how human actions harmonize with the environment. Monasteries and temples constructed during this period were often located in natural settings chosen according to Feng Shui principles, emphasizing seclusion, serenity, and alignment with natural energy flows.

Mountains (symbolizing stability) and flowing rivers (representing continuous prosperity) were considered highly auspicious sites for Buddhist institutions. Many temples from the Tang era, such as the Famen Temple near Xi’an, exhibit architectural layouts that reflect a conscious blending of spiritual doctrine and geomantic insight.

Meanwhile, Daoist alchemical practices, which sought to harmonize and refine the internal energies (Qi) of the human body, found a parallel in Feng Shui’s quest to harmonize external Qi within the environment. Daoist concepts such as the Three Treasures (San Bao: Jing, Qi, and Shen) became metaphorically linked to Feng Shui principles: just as Jing (essence), Qi (energy), and Shen (spirit) must be balanced within the body, so too must the landscape’s features—mountains, rivers, and man-made structures—be brought into dynamic equilibrium to foster health, longevity, and prosperity.

A particularly significant philosophical development during the Tang Dynasty was the formal articulation of the relationship between inner and outer environments. This was exemplified by the concept of the Mingtang (Bright Hall), a cosmological structure described in both Daoist and Buddhist writings.

In architectural Feng Shui, the Mingtang represents the open, bright space in front of a dwelling or temple, ideally framed by water and protected by surrounding landforms. This idealized arrangement mirrored the belief that a clear and vibrant spirit (Shen) required a luminous, unobstructed environment to thrive.

Additionally, important treatises on geomancy began to circulate during this period, further blending religious thought with practical Feng Shui application. Texts such as the “Classic of Burial” (Zang Shu) attributed to Guo Pu, though written slightly earlier, gained wide readership in the Tang era, providing a metaphysical rationale for site selection based on “Qi gathering” and the “embracing” forms of land and water.

By the end of the Tang Dynasty, Feng Shui had evolved beyond a mere art of placement into a comprehensive cosmological system, deeply tied to humanity’s spiritual quest for harmony with Heaven and Earth. The fusion of Buddhist compassion, Daoist naturalism, and Confucian orderliness gave Feng Shui a moral and ethical dimension that continues to inform its practice to this day.

Related reading: Geography’s Role in Feng Shui: Choosing the Right Location – Opens in new tab

Key Classical Feng Shui Texts by Period

| Text Name | Period Written | Key Focus/Theme | Historical Significance |

| I Ching (Book of Changes) | Pre-Qin (~1000 BCE) | Divination, trigrams, cosmology | Foundation for Yin/Yang, Bagua in Feng Shui |

| Zhou Li (Rites of Zhou) | Western Zhou (~1000 BCE) | Rituals, site selection | Early mention of spatial harmony |

| Zang Shu (Book of Burial) by Guo Pu | Jin Dynasty (c. 300 CE) | Ideal burial site features | Basis for Yin House Feng Shui |

| Shui Jing Zhu (Commentary on the Water Classic) | Southern Dynasties (~6th century) | Geography, water flow | Provided practical topographic reference |

| Water Dragon Classic (Qing Nang Jing) | Tang/Song Period (~600 CE) | Flow of qi through water channels | Core text on hydrological Feng Shui |

Song Dynasty (960–1279)

The Song Dynasty – comprised of the Northern Song (960 – 1127 A.D.) and the Southern Song (1127 – 1279 A.D.) – heralded the advancement of scientific and geographic technology and knowledge.

Feng Shui now effected decisions such as building sites, burial sites and the irrigation of the land which together had an enormous impact on the prosperity of a family.

The patronage of the various Song emperors was not always in evidence as some believed whilst others did not in the practice of feng shui. The emphasis on this time was on the external surroundings of a settlement, the internal arrangement was seen of secondary importance.

However, the combination of both in a harmonious fashion would lead to increased health and wealth. As well as auspicious locations for buildings, the idea of auspicious dates for the commencement of construction was also known and utilized which indicated a certain amount of superstition pervaded Feng Shui.

Also during this time, Feng Shui divided itself into two major schools:

- The Form School (Deals with evaluating topographical, geographic and waterways)

- The Compass School (Aka ‘Li Qi Pai’ – Regulating the form of energy)

🍀 Our “Feng Shui Master” app is your trusted companion, offering a useful guide to implementing Feng Shui principles. Try it now!

The Form School

The Form School was further enhanced and refined (circa 888 A.D.) through the teachings and practice of Yang Yun Sung, who at the time was an advisor to the Emperor.

Leading on from his work with the Form School, Sung laid the foundations for the Compass School. His works were further refined some 100 years later by Wang Chih (who’s work is now regarded as crucial texts upon which modern Compass School has been built).

The Compass School

The Compass School, as the name suggests, used a type of compass – the Luo Pan – (the compass itself was invented by the Chinese in the fourth century B.C.) to help determine Feng Shui positioning. In addition, this school used astrological patterns and numerology to determine the auspicious location for a new dwelling.

Starting during the 10th century, precise mathematical calculations relating to the compass points evolved. From ancient times, Chinese sages had known of the relationship between the earth’s gravitational field and it’s effects on animals and humans alike.

The Luo Pan was constructed as a ‘ready reckoner’ (a time-saver) aiding the feng shui expert determine the relationship between man, the earth and the heavens.

The Compass School originated in the North of China (where the relatively flat nature of the terrain necessitated the development of a different method to that of the Form School).

Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368)

The Yuan Dynasty, established by Kublai Khan in 1279, marked the first time that non-Han rulers governed all of China. Despite their foreign origins, the Mongol emperors recognized the sophisticated cultural and administrative systems of their Chinese subjects and, in many cases, chose to preserve and employ native practices, including the art of Feng Shui.

Kublai Khan himself commissioned Chinese geomancers and Confucian scholars in the planning and construction of the Yuan capital, Dadu (modern-day Beijing). The city’s layout adhered to strict Feng Shui principles, with its central axis running north-south, symbolic of imperial authority aligned with cosmic order.

The strategic placement of palaces, gates, and ceremonial halls followed geomantic logic, integrating concepts of balance between mountain protection (Xuanwu) to the north and open space (Mingtang) to the south. This demonstrated not only the Mongol rulers’ adoption of Chinese geomantic wisdom, but also their willingness to embrace it as a tool for asserting legitimacy over the Han population.

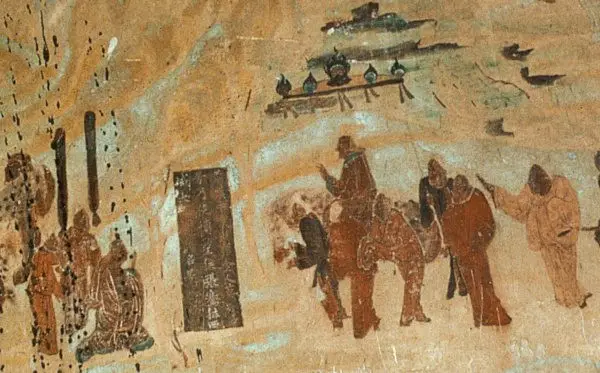

Under Mongol rule, the Yuan court became a cultural and intellectual melting pot, linking China with the broader Eurasian world. As a result, Feng Shui began to transcend ethnic and geographic boundaries. Chinese immigrants, artisans, and scholars traveled throughout the empire—reaching as far as Central Asia, Persia, and parts of Southeast Asia—bringing with them not only the Chinese written language and architectural styles but also geomantic knowledge.

In Korea, which had long been culturally tied to China, the Yuan period saw a renewed interest in site planning and grave orientation based on Chinese Feng Shui doctrines. The royal court of the Goryeo Dynasty, a vassal state under Mongol influence, invited Chinese geomancers to evaluate royal tomb sites and palace placements. These consultations shaped Korean geomancy (known as Pungsu-jiri) into a distinct but fundamentally derivative tradition.

In Japan, which was never successfully conquered by the Mongols but experienced cultural exchanges through trade and diplomacy, Feng Shui concepts began to appear more clearly in Heian-period capital designs, temple architecture, and city planning. The Japanese adaptation, known as Fūsui, took root particularly in esoteric Buddhist circles and among the aristocracy.

Meanwhile, in regions like Vietnam and the Malay Peninsula, Chinese merchant communities began applying Feng Shui principles in the siting of temples, clan halls, and residences. These early diasporic applications of Feng Shui reflect its functional adaptability and the universality of its core concepts—harmony with landforms, directional orientation, and the cyclical nature of energy.

The Yuan Dynasty was thus not only a period of imperial consolidation but also one of cultural transmission. While the Mongols may not have fully grasped the philosophical depth of Feng Shui, they facilitated its geographic spread and intercultural influence by promoting Chinese experts and allowing traditional practices to persist within the administrative machinery of the empire. This enabled Feng Shui to evolve into an increasingly global tradition, adapted by non-Han cultures and integrated into local cosmologies.

Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 A.D.), Feng Shui evolved from a primarily practical and spiritual tool into a scholarly discipline widely embraced by the literati and imperial bureaucracy. This era, characterized by Confucian revival and meticulous cultural refinement, provided fertile ground for the codification and documentation of Feng Shui principles.

The founder of the dynasty, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, is said to have employed Yin-Yang masters in the planning and construction of the capital city of Nanjing and later Beijing, ensuring the cities were harmonized with the surrounding mountains and waterways. The orientation of the Forbidden City, for instance—nestled between protective hills to the north and opening toward the south—was carefully aligned with Form School guidelines and cosmic directional symbolism rooted in the I Ching.

This period saw Feng Shui scholarship flourish, with many Confucian officials publishing texts that integrated geomantic thought with ritual propriety (Li 禮), astronomy, and civil engineering. The profession of Feng Shui consultant, once informal, now became a respected and structured pursuit, often passed down through family lineages or studied under scholarly mentorship. Scholars such as Xu Shanji and Zhang Juzheng wrote treatises that combined Five Phase theory, astrology, and landform assessment to evaluate human destiny and state affairs alike.

The Ming period also witnessed the wider circulation of Luo Pan compasses, now more refined and featuring multiple concentric rings denoting trigrams, directions, astrological signs, and time cycles. These instruments allowed for increasingly complex readings of both “Yang Zhai” (dwellings of the living) and “Yin Zhai” (burial sites), contributing to the surge in Flying Star Feng Shui (Fei Xing Pai) and Eight Mansion School (Ba Zhai Pai) practices—two of the most influential schools still in widespread use today.

As the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 A.D.) took hold under Manchu rule, Feng Shui retained its prominence, particularly among the Han Chinese elite and imperial architects. The Qing court embraced Feng Shui not only as a cultural relic but as a political and cosmological necessity. Every new palace, ancestral tomb, or governmental office was laid out in accordance with the principles of Heaven, Earth, and Man—the cosmic triad foundational to Chinese metaphysics.

One notable example is the continuation and refinement of imperial tomb planning, where entire burial complexes—such as the Eastern Qing Tombs and Western Qing Tombs—were constructed with mountain-water alignment, symbolic animal guardians, and directional feng shui elements. The placement of tombs was believed to influence the luck of descendants and the stability of the dynasty, a belief held with deep conviction.

In urban design, the Qing formalized many of the layout principles for residential compounds, particularly the siheyuan (courtyard house). These homes reflected auspicious orientation with the “Green Dragon” on the left (East), “White Tiger” on the right (West), “Black Tortoise” behind (North), and “Vermilion Bird” in front (South)—all metaphoric representations of ideal landform protection. Front doors were commonly placed on the eastern left side, referred to as the “Green Dragon Gate,” enhancing the flow of Qi into the home.

A testament to the reverence for classical masters is seen in the Qing court’s homage to Guo Pu (276–324 A.D.), the legendary geomancer whose texts became canonical references. So esteemed was Guo Pu’s poetry and geomantic theory that a Qing-era city was even named in his honor.

Despite the deep entrenchment of Feng Shui, the late Qing also witnessed rising tensions between science and tradition, particularly as Western ideologies, technology, and colonial critiques began influencing Chinese intellectual circles. Yet, even as political upheaval loomed, Feng Shui practice endured—transmitted both formally in scholarly circles and informally through village customs and folk beliefs.

Popular Feng Shui Methods Developed in Late Imperial China

| Method Name | Chinese Name | Origin Period | Focus Area | Key Application Example |

| Flying Star Method | 飞星法 (Fei Xing Fa) | Ming/Qing | Time-based energy shifts | Used to assess periodic changes in qi |

| Eight Mansion Method | 八宅法 (Ba Zhai Fa) | Qing Dynasty | Personal kua number & home | Optimizing bedroom/workspace placement |

| San He Method | 三合派 | Ming Dynasty | Environmental harmony | Ideal placement of buildings in landscapes |

| Destiny Number Method | 命卦 (Ming Gua) | Late Qing | Personal energy alignment | Individualized house matching |

| Purple Star Astrology | 紫微斗数 (Zi Wei Dou Shu) | Ming | Natal astrology | Life-path reading, timing of events |

Republican Era (1912–1949)

The Republican Era (1912–1949 A.D.), spanning from the fall of the Qing Dynasty to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, was a time of immense political upheaval, ideological conflict, and cultural transformation. During this period, Feng Shui—long embedded in imperial practice, Confucian ethics, and Daoist cosmology—entered a complex and often contradictory phase of decline, adaptation, and dispersal.

1. Anti-Superstition Movements and Political Reform

The new Republican government, driven by ideals of modernization, rationalism, and national rejuvenation, launched campaigns against what they termed “superstition” (迷信 míxìn)—a category that included geomancy, astrology, divination, and traditional religious rituals. Influenced by Western Enlightenment ideals and scientific materialism, reformers sought to replace traditional metaphysical frameworks with empirical science and education.

Feng Shui, despite its deep cultural roots, was increasingly framed as anti-modern and feudal. Educational institutions removed geomantic thought from textbooks, and many local ordinances banned the public advertising or consultation of Feng Shui masters, particularly in urban areas such as Shanghai, Nanjing, and Guangzhou. The practice was often driven underground or confined to rural communities where traditional beliefs remained strong.

Yet, even amid official resistance, Feng Shui persisted in private domains—especially among families seeking guidance for home construction, burial rites, and business ventures. It remained a silent but resilient force in everyday life, particularly in southern China where lineage halls, clan traditions, and ancestral worship were more entrenched.

2. Academic Interest and Early Ethnographic Studies

Interestingly, while the state suppressed popular practice, some scholars and anthropologists began to study Feng Shui systematically, documenting its cultural and historical value. Influential thinkers like Fei Xiaotong and Chen Ying treated geomancy not as superstition, but as a complex system of environmental adaptation and social organization. These early efforts laid the groundwork for viewing Feng Shui through the lens of cultural anthropology rather than pure mysticism.

In this way, Feng Shui began to be seen—by some—as a cognitive and symbolic system reflecting the Chinese worldview of harmony between Heaven (天), Earth (地), and Humanity (人). This opened the door to future reinterpretations that would emerge in the late 20th century.

3. The Rise of Overseas Feng Shui

Perhaps the most consequential development during the Republican era was the diaspora of Feng Shui knowledge. Faced with political instability, civil war, and anti-superstition sentiment, many Feng Shui masters and scholars migrated to regions such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, and later the West.

These emigrant masters established new lineages, published books in traditional Chinese, and passed on oral teachings that would eventually influence modern Feng Shui movements outside of mainland China. In cosmopolitan ports like Hong Kong, Feng Shui not only survived but thrived—becoming a prestigious advisory service for the city’s elite, architects, and business moguls. This offshore evolution preserved much of the classical tradition, free from the ideological restrictions unfolding in mainland China.

4. Tension Between National Identity and Tradition

The Republican period was ultimately a time of identity crisis for Feng Shui. It was caught between the drive to modernize and the urge to preserve heritage. While some viewed it as an outdated relic of dynastic superstition, others saw it as a repository of ancient wisdom that reflected the cultural DNA of the Chinese people.

By the end of the era, with the impending rise of the Communist government and further suppression on the horizon, Feng Shui stood at a crossroads. Its intellectual defense, survival in rural culture, and expansion through overseas communities ensured that it would not disappear—but rather transform and reemerge in the decades to come, ultimately finding new expressions in post-reform China and the global New Age movement.

Modern Era: Feng Shui and Urban Design in Post-Reform China

The reopening of China to the world following Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening-Up policy in 1978 marked a profound turning point in the country’s relationship with traditional knowledge systems. Once dismissed as superstition during the Cultural Revolution, Feng Shui reemerged cautiously at first, and then with increasing vigor, especially as urbanization, real estate development, and private entrepreneurship gained momentum.

As cities like Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Shanghai rapidly transformed from modest settlements into sprawling metropolises, Feng Shui quietly reasserted itself—not in overt slogans or official planning documents, but in the decisions made behind closed doors, by developers, architects, and government officials who sought to mitigate risk and attract prosperity. It became clear that, even within China’s new technocratic elite, there was a latent cultural memory and respect for geomantic wisdom.

In particular, the real estate boom of the 1990s and 2000s saw developers consulting Feng Shui masters to assess project viability. From the orientation of apartment complexes to the positioning of water features in corporate plazas, principles such as the flow of Qi, the command position, and the avoidance of “poison arrows” (sharp angles or hostile structures) became common criteria in project assessments. While not always officially acknowledged, the inclusion of Feng Shui audits was seen as a pragmatic insurance policy, blending tradition with market demands.

One of the most prominent examples is the layout of Beijing’s Central Business District (CBD) and its surrounding developments. Though modernist in form, the CBD’s major structures—such as the CCTV Headquarters and China World Trade Center Tower—have been critiqued and modified in alignment with Feng Shui recommendations, especially after early incidents (such as fires or unexplained budget overruns) were attributed to inauspicious orientations or structural imbalance.

Related reading: Surrounding Buildings that are BAD Feng Shui and How to Overcome Their Effect – Opens in new tab

Government projects, too, have not been immune. In Guangdong Province, the controversial case of the provincial government building in the 1990s—cited in local media for a string of misfortunes and deaths—led to extensive remodeling based on Feng Shui recommendations. The symbolic importance of correcting energy flow was seen as critical to restoring confidence, not only within the bureaucracy but also among the general public.

At the urban scale, modern Chinese planners have increasingly returned to the traditional ideals of harmonious landscape integration, championed by Feng Shui for centuries. New eco-cities and green belts are designed with mountain-water alignment (Shan Shui) in mind—reviving the age-old belief that a city backed by mountains and facing water invites stability and prosperity. Cities like Suzhou Industrial Park and Songdo (in collaboration with Korean developers) incorporate open spaces, strategic watercourses, and building massing that resemble principles from the Form School of Feng Shui.

Moreover, a quiet revival of Compass School techniques can be observed in luxury developments, where high-paying clients expect floorplans and unit orientations to match their Ba Zhai (Eight Mansions) or Ming Gua (Life Number) preferences. These calculations affect everything from which units command premium prices to how marketing language is tailored, often emphasizing health, wealth, and career growth opportunities in subtly Feng Shui-informed terms.

Academically, Feng Shui has also gained renewed legitimacy. Chinese universities such as Tsinghua and Peking University have sponsored research into traditional architecture and geomancy as part of their programs in cultural heritage and urban planning. A growing number of architectural firms and landscape designers are re-integrating Feng Shui principles into their design ethos, often branding it as “ecological design with Chinese characteristics.”

Today, Feng Shui stands at the intersection of tradition and modernity. It is not only a cultural inheritance but also a living, evolving framework being reinterpreted to meet the needs of a hyper-urban, environmentally conscious, and increasingly globalized China. As skyscrapers rise and bullet trains crisscross the land, the ancient wisdom of aligning human life with the rhythms of Heaven and Earth continues to guide the invisible hand behind many of the visible landmarks in post-reform China.

Impact of Political Regimes on Feng Shui Practice

| Political Era | Approach to Feng Shui | Key Outcomes |

| Imperial Dynasties | Embraced and institutionalized | Official building plans and tombs aligned |

| Republican Era (1912–49) | Suppressed as superstition | Went underground; masters migrated abroad |

| Maoist Era (1949–76) | Outlawed during Cultural Revolution | Private practice vanished or stayed rural |

| Reform Era (Post-1978) | Quiet resurgence and academic interest | Reintegrated into urban planning, business design |

| Digital Age (2000s–now) | Globalization and hybridization | Used in tech tools, real estate, and wellness |

Feng Shui in the Digital Age: AI, Algorithms, and Virtual Space

As humanity enters an era increasingly defined by artificial intelligence, virtual environments, and algorithm-driven architecture, the ancient principles of Feng Shui are finding novel expressions beyond the physical world. No longer confined to landforms, bricks, and mortar, Feng Shui is now being adapted to digital landscapes and smart environments, where the concept of Qi—once flowing through rivers and valleys—now permeates through data streams, network architecture, and user interfaces.

At the core of this modern transformation is the rise of AI-powered Feng Shui platforms. These systems combine millennia-old geomantic knowledge with advanced analytics, satellite mapping, and real-time spatial data. Homebuyers, interior designers, and even urban developers now use mobile apps or online services that generate automated Feng Shui audits—evaluating auspicious directions, elemental balance, and personal BaZi charts based on geolocation and AI pattern recognition. What once required the physical presence of a Feng Shui master can now be simulated by algorithm, offering personalized advice at scale.

Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) tools further blur the boundary between physical and digital Feng Shui. Designers of metaverse platforms and gaming environments are increasingly embedding Feng Shui concepts into digital architecture, ensuring that virtual homes, office spaces, or even entire virtual cities are constructed in a way that respects directional harmony and symbolic placement. In this realm, Qi becomes metaphorical but still potent—affecting user experience, emotional response, and perceived prosperity within the virtual space.

Furthermore, in the world of user interface (UI) and experience design (UX), some technologists have begun applying Feng Shui analogies to digital layouts. The balance between white space and content, the placement of call-to-action buttons, and the flow of navigation mirrors the “clear front, supportive back, protective sides” philosophy of Form School. Here, Feng Shui principles are translated into digital ergonomics—creating harmonious, intuitive, and psychologically “auspicious” interfaces.

Corporate offices in the tech sector, particularly in cities like Shenzhen, Hangzhou, and Singapore, now employ data-informed Feng Shui consultations for their smart buildings. These include biometric feedback loops, environmental sensors, and AI-driven climate systems that adjust lighting, airflow, and even scent based on real-time energy readings—seamlessly blending traditional wisdom with smart technology to create a living, responsive Qi environment.

In academia and speculative architecture, discussions are emerging around “digital geomancy”, a discipline that explores how ancient spatial intuitions—like the Bagua or Lo Shu Square—might inform the structuring of non-Euclidean virtual realities, quantum computing environments, or even extraterrestrial settlement design. Researchers have begun asking: can a Mars colony benefit from Feng Shui? Can a satellite orbit be mapped using dragon veins?

Critics of this digital translation caution against the commodification and dilution of Feng Shui’s philosophical core, warning that algorithmic interpretations risk reducing a deeply spiritual and contextual practice into a set of checkboxes. In response, contemporary Feng Shui masters are working to reinterpret ancient texts with modern metaphors—teaching how the flow of energy in cyberspace still aligns with Taoist ideas of balance, transformation, and harmony.

Ultimately, Feng Shui in the digital age is not a departure from tradition but rather its evolution. Just as the compass and calendar once modernized ancient divination, today AI and virtual tools offer a new kind of Luo Pan—one that measures not only cardinal direction, but also digital intention. The Qi of the 21st century flows through fiber optics and code, and Feng Shui continues its timeless task: to help humanity live in accordance with the invisible rhythms of the world—now both real and virtual.

🍀 Our “Feng Shui Master” app is your trusted companion, offering a useful guide to implementing Feng Shui principles. Try it now!

Final Thoughts

From ancient burial grounds and imperial city planning to AI-driven energy mapping, the journey of Feng Shui is as dynamic as the qi it seeks to harmonize. Across dynasties and decades, this enduring practice has evolved—absorbing philosophy, science, and culture—yet always returning to its core purpose: aligning human life with the rhythms of nature.

As we continue to shape our modern world, Feng Shui reminds us that balance, intention, and respect for the environment are timeless guides to prosperity and peace.

Want to learn more about Feng Shui? Take a look at these Courses and Books – Aff.link

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook

Featured Image By Pixabay.com