For much of history, women in China were expected to follow the “Three Obediences and Four Virtues” (三从四德), a Confucian doctrine that emphasized submission to fathers, husbands, and sons. Their roles were largely confined to domestic duties, child-rearing, and maintaining the family’s honor. Education was often reserved for men, and political power was seen as a male domain.

However, this rigid structure did not mean that women had no influence. In noble and imperial families, women could hold sway behind the scenes, advising rulers, managing vast households, and even making critical decisions in times of crisis.

Some gained power through marriage or motherhood, serving as empresses, dowagers, and advisors. Others took a more unconventional route, leading armies, engaging in diplomacy, or shaping intellectual and cultural thought.

Their success often came at great risk. Accusations of manipulation, cruelty, or breaking moral codes followed many powerful women. In a world where female authority was viewed as unnatural, they had to be not only intelligent and resourceful but also politically shrewd. Through careful strategy, personal ambition, and in some cases, sheer force, these women left indelible marks on Chinese history.

The legacies of these remarkable women extend far beyond ancient history. Their struggles, triumphs, and sacrifices reflect the universal challenges faced by women striving for recognition and influence. They defied expectations, proving that leadership is not defined by gender but by vision and ability.

Today, their stories serve as powerful reminders of resilience, determination, and the pursuit of equality. By learning about these trailblazers, we gain not only a deeper understanding of China’s past but also inspiration for the ongoing fight for women’s empowerment worldwide.

Lady Hao (妇好): The Warrior Queen of the Shang Dynasty

For centuries, Lady Hao (妇好) was little more than a name whispered in ancient texts, her true legacy obscured by time. Unlike many other powerful women in Chinese history, her story was not passed down through elaborate legends or romanticized folklore. Instead, it was rediscovered through archaeology, revealing a woman who was far more than just a consort—she was a military leader, a high priestess, and a political force in the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE).

The Shang Dynasty is known as one of the earliest recorded civilizations in China, ruled by a lineage of warrior-kings who communicated with the divine through oracle bones. These inscribed bones, used for divination, provided some of the earliest written records of Chinese history—and it was within these ancient scripts that Lady Hao’s true power was uncovered.

Leading Armies and Conducting Rituals: Lady Hao’s Multifaceted Role

Unlike most women of her time, Lady Hao was not confined to the inner court. As one of King Wu Ding’s (武丁) many wives, she distinguished herself through intelligence, military prowess, and religious influence. Oracle bone inscriptions describe her as a formidable general who led thousands of troops into battle against enemy states such as the Tu-Fang and Qiang. These were not symbolic roles—she personally commanded forces, orchestrated strategies, and secured significant victories for the Shang kingdom.

Beyond her military achievements, Lady Hao was also a high priestess. In the Shang Dynasty, rulers depended on divine guidance for governance, and religious rituals were central to political power. Lady Hao performed these sacred ceremonies, communicating with ancestors and deities on behalf of the king. This dual role as both warrior and spiritual leader set her apart, making her one of the most influential figures of her time.

Archaeological Discoveries: Evidence of Her Power and Influence

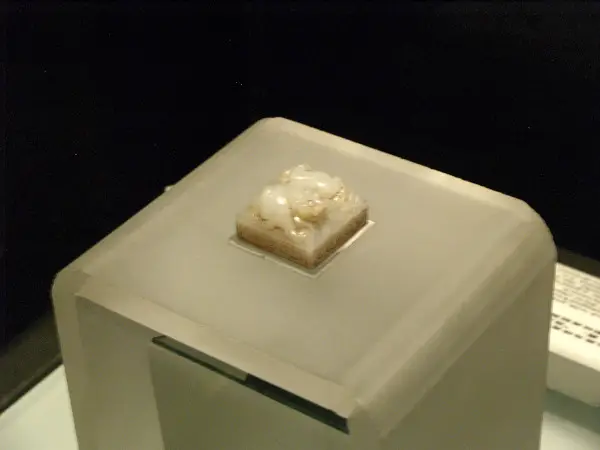

The greatest confirmation of Lady Hao’s power came in 1976 when archaeologists uncovered her tomb at the ruins of Yin, near modern-day Anyang. Unlike many other royal burials that had been looted over time, her tomb remained largely intact, offering a wealth of artifacts that spoke to her status.

Inside, researchers found over 1,600 burial goods, including bronze weapons, jade ornaments, and ritual vessels. The presence of axes, swords, and helmets reinforced her military identity, while the vast number of ceremonial objects highlighted her role in religious and political affairs. The tomb also contained 16 human sacrifices and dozens of animal remains—common practices in Shang royal burials, further proving her elite status.

These findings transformed Lady Hao from a name in oracle inscriptions into a fully realized historical figure. She was not just a queen or a wife; she was a ruler in her own right, defying the expectations of her era and commanding both armies and spiritual authority.

Her story challenges long-held perceptions of ancient Chinese women as passive figures, showing that even in a deeply patriarchal society, exceptional women could rise to power and leave a lasting legacy.

Lady Xian (冼夫人): The Saint Mother of Lingnan

Lady Xian (冼夫人), also known as Xian Zhen, was a remarkable leader during one of the most politically volatile periods in Chinese history. Born in 512 CE into the Xian clan of the Li people in what is now Guangdong Province, she lived through the Liang, Chen, and Sui dynasties. Her life was marked by her ability to navigate complex political landscapes and maintain stability in the Lingnan region, a territory often plagued by rebellion and unrest.

As a hereditary chieftain, Lady Xian inherited leadership at a time when neighboring clans frequently clashed. Yet, she distinguished herself by prioritizing diplomacy over conflict. She worked tirelessly to mediate disputes and foster peace among the various ethnic groups in her region. Her wisdom and fairness earned her widespread respect, even from the imperial courts of three successive dynasties. Emperor Chen Shubao of the Chen dynasty recognized her contributions by bestowing upon her the title “Lady of Qiaoguo,” a rare honor for a woman of her time.

A Revered Leader Who Maintained Peace and Unity

Lady Xian’s legacy as the “Saintly Mother of Lingnan” stems from her extraordinary efforts to unify and stabilize the southern regions of China. Her leadership extended beyond her own clan; she actively worked to integrate the Baiyue people with Han Chinese culture, promoting intermarriage and cultural exchange. This not only reduced ethnic tensions but also strengthened regional cohesion under imperial rule.

Her influence was not limited to diplomacy. Lady Xian played a critical role in suppressing rebellions and maintaining order. For instance, during the Hou Jing Rebellion (548–550 CE), she successfully dissuaded her husband, General Feng Bao, from joining the insurgents. Instead, they supported Chen Baxian (later Emperor Wu of Chen) in quelling the uprising, earning her recognition as a stabilizing force in the region.

Lady Xian’s impartiality and incorruptibility further solidified her reputation. She was known for resolving disputes fairly and punishing wrongdoers within her own clan to uphold justice. Her governance style combined strict discipline with compassion, creating a sense of security for both her people and neighboring communities.

Lady Xian’s Impact on Regional Stability

Lady Xian’s contributions went beyond maintaining peace; she actively shaped the cultural and economic development of Lingnan. She abolished human trafficking practices that were rampant in the region, advocating for ethical governance and loyalty to the state. Her efforts to integrate local customs with Han feudal culture laid the groundwork for greater unity between different ethnic groups.

Her military acumen also played a significant role in stabilizing Lingnan. By enforcing strict discipline among her troops and promoting non-violent solutions whenever possible, she quelled civil disturbances without unnecessary bloodshed. Her strategy of “to rule is superior to do battle” exemplified her preference for governance over warfare—a philosophy that resonated deeply with local leaders.

Even after her death in 602 CE, Lady Xian’s legacy endured. She was honored with numerous posthumous titles across dynasties, reflecting her lasting impact on Chinese history. Temples dedicated to her memory were built throughout Lingnan and beyond, serving as symbols of unity and reverence for generations.

Related reading: The Role of Women in Ancient China: A Journey Through Time – Opens in new tab

Empress Lü Zhi (吕雉): The First Woman to Rule China

Lü Zhi (吕雉), later known as Empress Lü, began her journey to power as the wife of Liu Bang, the eventual founder of the Han dynasty. Born in 241 BCE in Shanfu County during the late Qin dynasty, Lü was married off by her father to Liu Bang, who was then a low-ranking official. Her father recognized Liu’s potential, setting the stage for her future rise. Together, they had two children: Princess Yuan of Lu and Liu Ying, who would later ascend as Emperor Hui of Han.

Lü Zhi’s path to prominence was shaped by turbulent times. During Liu Bang’s rebellion against the Qin dynasty, Lü and her children were captured by Xiang Yu, Liu’s rival in the struggle for control over China. Despite enduring captivity, Lü remained steadfast and played a critical role in supporting Liu Bang’s eventual victory at the Battle of Gaixia in 202 BCE. With China unified under Liu Bang’s rule, Lü Zhi became the first woman to hold the title of Empress of China.

The Han Dynasty’s First Empress Dowager

Lü Zhi’s influence expanded significantly after Liu Bang’s death in 195 BCE. As empress dowager, she assumed a central role in governance during the reigns of her son Emperor Hui and his successors. Her position as regent marked a turning point in Chinese history, as she effectively became the first female absolute ruler of a united China.

Empress Dowager Lü was not content with merely advising; she wielded authority directly. She issued imperial edicts under her own name and adopted titles traditionally reserved for emperors, such as Zhen (朕), a pronoun exclusive to sovereigns. Her control over the court and military solidified her dominance during this period. Despite Emperor Hui’s initial resistance to her ruthlessness—particularly after witnessing her brutal treatment of rivals—he eventually ceded power entirely to his mother.

Political Intrigues and Ruthless Tactics

Lü Zhi’s reign was marked by both administrative competence and ruthless tactics that earned her a controversial reputation. She skillfully managed court politics but did not hesitate to eliminate threats to her authority. One infamous example was her revenge against Concubine Qi, whom she perceived as a rival due to succession disputes. Lü Zhi subjected Qi to horrific torture, turning her into what historical accounts describe as a “human swine”. This act shocked even her son Emperor Hui, leading him to withdraw from active governance.

Her political maneuvers extended beyond personal vendettas. Lü Zhi orchestrated the deaths of prominent generals like Han Xin and Peng Yue to consolidate power within the imperial court. She also elevated members of her own clan into key positions, creating a network of loyal allies that ensured her dominance over Han politics. However, this nepotism ultimately led to instability; after her death in 180 BCE, the Lü Clan Disturbance resulted in their downfall and marked an end to her family’s political influence.

The Legacy of Her Rule

Empress Lü Zhi left behind a complex legacy that continues to provoke debate among historians. On one hand, she demonstrated remarkable administrative ability during her reign. Under her leadership, the Han dynasty experienced stability and prosperity despite internal challenges. Her ability to govern effectively in a patriarchal society set an important precedent for women in positions of power.

On the other hand, her ruthless actions have overshadowed many of her achievements. Historical accounts often portray her as both capable and tyrannical—a ruler who maintained order but at great moral cost. The Lü Clan Disturbance following her death highlights how fragile dynastic stability can be when built on personal ambition rather than institutional integrity.

Nevertheless, Lü Zhi’s story remains significant as it illustrates both the possibilities and perils faced by women who defied societal norms to wield power in ancient China.

Wu Zetian (武则天): The Only Female Emperor of China

Wu Zetian’s ascent to power is one of the most remarkable stories in Chinese history. Born in 624 CE to a wealthy family, Wu received an exceptional education for a woman of her time, studying literature, history, and music. Her intelligence and beauty caught the attention of Emperor Taizong, who brought her into the palace as a concubine at the age of 14. While serving as a low-ranking consort, Wu impressed the emperor with her administrative skills and gained access to imperial affairs, setting the stage for her future ambitions.

After Emperor Taizong’s death in 649 CE, Wu briefly became a Buddhist nun but soon returned to court as a concubine to Taizong’s successor, Emperor Gaozong. Her rise accelerated when she strategically maneuvered to remove Empress Wang and another favored consort, securing her position as empress in 655 CE. Wu Zetian’s political acumen allowed her to dominate court affairs even before officially taking the throne.

Breaking Barriers: How She Took the Throne

Wu Zetian shattered gender norms by becoming China’s only female emperor. Following Emperor Gaozong’s debilitating stroke in 660 CE, Wu effectively governed as his administrator, wielding authority equal to that of the emperor. After Gaozong’s death in 683 CE, she refused to retire or cede power to her sons, as tradition dictated. Instead, she continued ruling as empress dowager through her sons Zhongzong and Ruizong.

In 690 CE, Wu formally declared herself emperor by founding the Zhou dynasty, replacing the Tang dynasty temporarily. She held an elaborate coronation ceremony and changed the royal family name from Li to Wu to legitimize her rule. This bold move marked a significant break from tradition and solidified her unprecedented position as sovereign ruler.

Her Reforms and Contributions to Chinese Society

Wu Zetian’s reign brought substantial reforms that revitalized China’s culture and economy. She lowered taxes, encouraged agricultural development through irrigation projects, and reduced forced labor requirements for peasants. Her policies allowed farmers to retain more of their produce, contributing to widespread prosperity.

Wu also elevated Buddhism as China’s state religion, commissioning numerous temples and statues while promoting Buddhist teachings that supported her legitimacy as ruler. She circulated texts like the Great Cloud Sutra, which prophesied a female monarch bringing peace and prosperity. Additionally, she diminished the influence of aristocratic clans in government by promoting officials based on merit rather than lineage.

Under her leadership, China expanded its borders and strengthened international trade relations via the Silk Road. Her focus on cultural patronage led to artistic achievements in ceramics, sculpture, and literature that flourished during her reign.

Myths and Truths: Was She a Tyrant or a Visionary?

Wu Zetian remains one of history’s most polarizing figures. Confucian historians often portrayed her as ruthless and cruel, accusing her of infanticide, torture, and executing rivals—including members of her own family—to consolidate power. These accounts were likely influenced by patriarchal biases against female rulers.

However, modern interpretations view Wu Zetian as a visionary leader who defied societal norms and brought stability during her reign. Her policies improved governance, reduced corruption, and fostered economic growth. While she undoubtedly employed ruthless tactics to maintain control, they were not uncommon among rulers of her time.

Wu Zetian’s legacy is complex—she was both a trailblazer who broke barriers for women and a pragmatic ruler whose methods reflected the harsh realities of imperial politics.

Ban Zhao (班昭): The Scholar Who Shaped Confucian Thought

Ban Zhao (班昭) (45-120 CE) was a remarkable figure who defied the gender norms of her time to become China’s most famous female scholar. Born into a prestigious family of historians and intellectuals, Ban Zhao received an exceptional education rarely afforded to women in ancient China. Her intellectual pursuits flourished despite living in a patriarchal society that generally limited women’s roles.

As a historian, philosopher, and politician, Ban Zhao made significant contributions to Chinese scholarship. She completed the monumental “Book of Han” after her brother’s death, becoming the first known female Chinese historian. Her expertise extended to astronomy, mathematics, and poetry, showcasing her diverse intellectual interests.

Her Famous Work: Lessons for Women

While Ban Zhao contributed significantly to historical writing, she is best known for her treatise Lessons for Women (Nü Jie), a Confucian text that outlined the virtues and expectations of women in Han society. Written as a guide for her daughters, the book emphasized humility, obedience, diligence, and morality—qualities that Confucian teachings considered ideal for women.

The text advised women to respect their husbands and prioritize family harmony, but it also encouraged them to be educated. Ban Zhao argued that a well-educated woman could better fulfill her roles as a wife and mother, subtly challenging the idea that women should remain entirely passive and ignorant. Her advocacy for female literacy was groundbreaking, as it recognized women’s intellectual capabilities within the constraints of Confucian traditions.

“Lessons for Women” contained seven chapters covering topics such as:

- Humbleness

- Husband and Wife relationships

- Respect and Caution

- Womanly Qualifications

- Whole-hearted Devotion

- Implicit Obedience

- Harmony Between Younger In-laws

Educating Women in Confucian Ethics

Unlike many of her male contemporaries, Ban Zhao believed that education was not just for men. As a tutor to the empress and the women of the imperial court, she played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual lives of noblewomen. Her teachings helped these women navigate court politics and contribute to the governance of the empire from behind the scenes.

Though her views on gender roles largely aligned with Confucian ideals, her emphasis on education for women planted the seeds for future discussions on gender equality in Chinese thought. In an era where most women were excluded from formal learning, Ban Zhao’s influence gave noblewomen an opportunity to cultivate their intellect and refine their moral character.

Related reading: Exploring The Importance Of Family In Chinese Culture – Opens in new tab

Her Influence on Later Generations

Ban Zhao’s legacy is complex and continues to spark debate among scholars. Some modern interpretations view her as a pioneering feminist who subtly challenged gender norms by advocating for women’s education. Others argue that her emphasis on women’s subservience reinforced patriarchal structures.

Regardless of interpretation, Ban Zhao’s influence on later generations is undeniable. “Lessons for Women” became one of the “Four Books for Women” that shaped female education in China for centuries. Her work opened doors for women’s involvement in scholarly activities throughout Chinese society.

Later female scholars and poets, such as Li Qingzhao of the Song Dynasty, benefited from the precedent Ban Zhao set.

Her contributions to history, literature, and Confucian thought secured her a place as one of the most important female intellectuals in Chinese history. While some view her writings as restrictive to women’s independence, others recognize her as a pragmatic figure who worked within the constraints of her time to advocate for female education—an achievement that helped shape the cultural fabric of China for generations.

Academic paper: Confucian Humanism and the Importance of Female Education: The Controversial Role of Ban Zhao by Jana S. ROŠKER

Princess Pingyang (平阳公主): The Warrior Who Founded a Dynasty

Princess Pingyang (平阳公主) was not an ordinary woman of ancient China. Born in 600 CE, was the third daughter of Li Yuan, a prominent military commander of the Sui Dynasty who would later become Emperor Gaozu, the founder of the Tang Dynasty.

Her mother, Duchess Dou, came from an influential family, giving Pingyang a privileged upbringing steeped in both political and cultural traditions. Despite being born into nobility, Pingyang’s early life was marked by the political instability of the Sui Dynasty under Emperor Yangdi, a ruler infamous for his tyranny.

As a young woman, Princess Pingyang married Chai Shao, a palace guard commander. This union placed her in the capital city of Chang’an, where she witnessed firsthand the discontent brewing among the people under Emperor Yangdi’s rule. Her noble birth and marriage positioned her at the crossroads of power and rebellion, setting the stage for her extraordinary contributions to Chinese history.

Instead of staying behind in safety, she made a bold choice: she left her privileged life to support her father’s cause, proving that she was as courageous as any male warrior of her time.

Leading the “Army of the Lady” to Victory

In 617 CE, Li Yuan launched a rebellion against Emperor Yangdi, aiming to overthrow the Sui Dynasty. Princess Pingyang did not merely support the rebellion—she actively led it. While her father and brothers gathered forces elsewhere, she took charge of securing the eastern regions of the empire.

Disguising herself in male attire to avoid detection, she returned to her family estate in Taiyuan.With remarkable leadership skills, she recruited thousands of troops, forming what became known as the “Army of the Lady” (娘子军).

Pingyang’s leadership was as strategic as it was compassionate. She used her family’s wealth to provide food and aid to starving villagers, earning their loyalty and inspiring many to join her cause. Her army grew rapidly to an estimated 70,000 troops, composed largely of peasants and defectors from Sui forces.

Unlike other armies of the time that relied on looting and pillaging, Pingyang’s forces adhered to strict discipline under her command. They distributed food and supplies to communities they passed through, gaining widespread support and admiration.

Her military campaigns were decisive and skillfully executed. Pingyang captured key cities and strongholds in Guanzhong, significantly weakening Sui control over the region. Her victories culminated in her pivotal role during the final battle for Chang’an, where she joined forces with her father and husband to secure their triumph over the Sui Dynasty.

Her Role in Establishing the Tang Dynasty

Princess Pingyang’s contributions were instrumental in establishing the Tang Dynasty. Her victories not only ensured military success but also solidified popular support for her father’s claim to the throne. In 618 CE, after Emperor Yangdi’s defeat and death, Li Yuan declared himself Emperor Gaozu of Tang.

Pingyang was granted the title “Princess Zhao” (meaning wise and virtuous) as recognition for her extraordinary efforts. She was celebrated not only as a skilled military leader but also as a unifying figure who inspired loyalty across social classes. Her leadership demonstrated that compassion and discipline could coexist with martial strength—a rare combination that set her apart from other commanders of her time.

How Her Contributions Were Remembered

Tragically, Princess Pingyang passed away in 623 CE at just 23 years old. Despite her young age, her legacy endured as one of China’s most remarkable women leaders. When officials from the Ministry of Rites opposed granting her a military funeral on account of her gender, Emperor Gaozu fiercely defended his daughter’s contributions. He declared that “she was no ordinary woman” and ensured she received a grand military funeral complete with full honors—a rare distinction for women at that time.

Over centuries, Princess Pingyang has been remembered as a symbol of courage, compassion, and leadership. Her story is often compared to legendary heroines like Mulan but stands out for its historical authenticity and scale of impact.

In later centuries, she became an inspiration for women who sought to challenge traditional roles, proving that strength and strategy were not limited by gender.

Her story is a rare and powerful example of female leadership in a time when warfare and politics were almost exclusively male domains. Even today, Princess Pingyang stands as a reminder that women, too, can be warriors and nation-builders.

Consort Yu (虞姬): The Tragic Heroine of Ancient China

Consort Yu (虞姬), also known as “Yu the Beauty,” was the beloved wife of Xiang Yu (项羽), the Hegemon-King of Western Chu. Their romance is one of the most poignant and tragic love stories in Chinese history. Born around 224 BCE in present-day Jiangsu, Consort Yu was renowned for her beauty and grace. She met Xiang Yu through her brother, who joined his rebellion against the Qin dynasty. Captivated by her charm, Xiang Yu married her and made her his imperial consort.

Their bond was inseparable; Consort Yu accompanied Xiang Yu on his military campaigns during the Chu-Han Contention (206–202 BCE), a civil war between Xiang Yu and Liu Bang, founder of the Han dynasty.

Through victories and defeats, she remained by his side, sharing in both his glory and despair. Their love was immortalized in poetry, songs, and operas, making them symbols of devotion and sacrifice.

Her Role in the Chu-Han Contention

Consort Yu played a unique role during the Chu-Han Contention. While her direct political influence is unclear, she played a crucial role as a source of emotional support for Xiang Yu. In times of despair, she comforted him; in moments of triumph, she celebrated with him.

Her presence symbolized loyalty, a quality that Xiang Yu’s closest followers admired and sought to emulate. Her presence bolstered morale among his troops and reinforced Xiang Yu’s determination to fight for supremacy over China.

The final chapter of their story unfolded at the Battle of Gaixia in 202 BCE. Xiang Yu’s army was surrounded by Han forces led by Liu Bang’s general Han Xin. The Han soldiers sang Chu folk songs to demoralize Xiang Yu’s troops, creating the illusion that many had defected to Liu Bang’s side. As morale plummeted, Xiang Yu composed the famous “Song of Gaixia” (《垓下歌》), lamenting his lost strength and uncertain future with Consort Yu.

The Legend of Her Sacrifice

Consort Yu’s sacrifice is one of the most enduring legends from this era. As Xiang Yu despaired over their impending defeat, Consort Yu performed a graceful sword dance for him while singing a sorrowful response to his lament. Her song expressed her willingness to die alongside him rather than live in captivity under enemy rule.

Moved by her devotion, Xiang Yu watched as she took her own life with his sword after completing her dance. Her selflessness was an act of love and loyalty—she believed her death might allow Xiang Yu a chance to escape unburdened by concern for her safety.

Xiang Yu, devastated by her death, fought his way out of the encirclement but eventually took his own life rather than surrender. The tragic end of their story immortalized Consort Yu as a heroine whose love and loyalty transcended death.

Related reading: Meet The Four Great Beauties of Ancient China – Opens in new tab

How She Became a Symbol of Loyalty and Love

Consort Yu’s tragic story has resonated across centuries as a symbol of unwavering loyalty and love. Her devotion to Xiang Yu has been immortalized in literature, art, and performances such as the Peking opera The Hegemon-King Bids Farewell to His Lady. Poets like Su Shi and Yuan Mei have written about her sacrifice, further cementing her place in Chinese cultural memory.

Her legendary farewell song, Gaixia Ge (《垓下歌》), has been passed down through generations, reinforcing her image as a symbol of unwavering love and sacrifice. In Chinese culture, she represents not just the tragic fate of a lover, but also the ideal of loyalty in its purest form.

Her tomb, known as “Tomb of the Beauty,” stands in Lingbi County, Anhui Province, attracting visitors who pay homage to her enduring legacy. In popular culture, she remains an icon of romantic tragedy—a heroine whose love transcended life itself.

Though history has largely been written by the victors—Liu Bang and his Han successors—Consort Yu’s legacy endures. Her story remains a poignant reminder of love and loss in the face of war, and she continues to inspire works of art, literature, and performance in modern times.

Empress Dowager Cixi (慈禧太后): The Woman Behind the Throne

Empress Dowager Cixi’s rise from a low-ranking concubine to one of the most powerful figures in Chinese history is nothing short of extraordinary. Born in 1835 into the Yehe Nara clan, she entered the Forbidden City at the age of sixteen as a concubine to the Xianfeng Emperor.

Her fortunes changed dramatically in 1856 when she gave birth to the emperor’s only son, Zaichun, securing her position within the imperial court. Upon the emperor’s death in 1861, her five-year-old son ascended the throne as the Tongzhi Emperor, and Cixi seized the opportunity to gain political control.

Cixi’s initial step toward power came through a palace coup against the regents appointed by her late husband. She allied herself with Empress Dowager Ci’an and key political figures, including Prince Gong, to oust her rivals. This bold move established her as co-regent alongside Ci’an, marking the beginning of her decades-long reign behind the throne.

Controlling the Qing Dynasty from Behind the Curtain

As empress dowager, Cixi ruled China from behind a silk screen—a symbolic barrier separating her from male officials during court sessions. Despite this physical separation, her influence was absolute. She effectively governed through regency during the reigns of both her son, Emperor Tongzhi, and later her adoptive nephew, Emperor Guangxu. Cixi’s political acumen allowed her to consolidate power and navigate court intrigues with remarkable skill.

Cixi oversaw major reforms during the Tongzhi Restoration, a period aimed at revitalizing the Qing dynasty after years of internal rebellion and foreign aggression. While she resisted Western-style governance, she supported technological advancements such as railways, telegraphs, and modern weaponry. Her ability to balance tradition with modernization helped sustain the dynasty through turbulent times.

However, Cixi’s reign was not without controversy. Her decision to place Emperor Guangxu under house arrest following his support for radical reforms during the Hundred Days’ Reform of 1898 highlighted her resistance to rapid change. Critics often portray her as a reactionary figure who prioritized stability over progress.

Modernization and Rebellion: Her Controversial Decisions

Cixi’s leadership faced significant challenges during national crises such as the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901). Initially backing the anti-foreign Boxer groups and declaring war on invading Allied forces, she later reversed course after their defeat. The occupation of Beijing by foreign powers marked a humiliating moment for China and exposed Cixi’s miscalculations.

In response to this setback, Cixi implemented sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing China. She abolished practices like foot-binding and gruesome punishments such as “death by a thousand cuts.” Additionally, she laid groundwork for constitutional monarchy by initiating fiscal reforms and proposing parliamentary elections—a bold move for an empire steeped in tradition.

Despite these efforts, many historians debate whether Cixi’s decisions ultimately contributed to the Qing dynasty’s decline. Her balancing act between modernization and preserving imperial authority left China vulnerable to internal divisions and external pressures.

The End of an Era: Her Final Years and Lasting Impact

Empress Dowager Cixi died in 1908 at age 72, just one day after Emperor Guangxu—whom she allegedly ordered poisoned. Her death marked the end of an era for both China and its monarchy. The throne passed to Puyi, a two-year-old boy whose reign would witness the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911.

Cixi’s legacy remains deeply polarizing. Some view her as a visionary modernizer who brought medieval China into the modern age through technological advancements and social reforms. Others criticize her as a conservative autocrat whose resistance to change hastened imperial collapse.

Regardless of perspective, Cixi’s story is a testament to her resilience and ability to wield power in a male-dominated society. Her reign shaped China’s trajectory during one of its most transformative periods, leaving an indelible mark on history.

The Cultural and Political Impact of Powerful Women

Throughout China’s long history, powerful women have left an undeniable mark on dynastic politics. Whether as warriors, rulers, scholars, or diplomats, these women influenced the course of history in ways that defied societal norms.

Empress Lü Zhi established the precedent for female political power in the Han Dynasty. Wu Zetian shattered all barriers by becoming the only woman to rule China as emperor. Empress Dowager Cixi, from behind the scenes, controlled the Qing court for nearly half a century. Each of these women played a critical role in the success, transformation, or downfall of their respective dynasties.

Meanwhile, figures like Princess Pingyang and Lady Hao contributed to dynastic foundations through military leadership. Pingyang’s “Army of the Lady” was instrumental in establishing the Tang dynasty, while Lady Hao’s command of Shang armies demonstrated women’s capacity for strategic warfare.

Beyond governance, women like Ban Zhao helped shape intellectual and cultural traditions. Her work Lessons for Women influenced Confucian thought for generations, defining women’s roles in education and family life.

Related reading: The Fearless Feminist of China: The Life and Legacy of Qiu Jin – Opens in new tab

The Struggles They Faced in a Patriarchal Society

Despite their achievements, powerful women in ancient China faced immense obstacles. Confucian ideology, which emphasized male authority and female obedience, often worked against them. Even when women gained power, they were frequently portrayed as ruthless or manipulative. Lü Zhi was feared for her political cunning, Wu Zetian was branded a tyrant, and Cixi was blamed for China’s decline—yet their male counterparts, who engaged in similar political maneuvers, were often celebrated as strong rulers.

Moreover, many of these women had to operate from behind the scenes. Empress dowagers wielded influence through their sons, and female scholars like Ban Zhao had to frame their teachings within the constraints of Confucian ideals. Even those who directly led armies, such as Princess Pingyang, saw their contributions minimized in official records. Their struggles highlight the challenges women faced in gaining recognition, even when their impact was undeniable.

Their Influence on Women’s Roles in Later Centuries

The legacies of these women extended far beyond their lifetimes. Wu Zetian’s reign inspired debates about female leadership that persisted for centuries. Her example demonstrated that women could govern effectively, challenging traditional gender norms. Similarly, Ban Zhao’s writings on Confucian ethics for women became foundational texts for female education in later dynasties, influencing how women were perceived and educated.

While many of these women operated within patriarchal frameworks, their stories inspired future generations to question societal norms. Figures like Princess Pingyang and Consort Yu became symbols of loyalty and courage in Chinese folklore and literature. Even as neo-Confucianism during the Song dynasty imposed stricter limitations on women’s roles, their contributions served as reminders of what women could achieve under extraordinary circumstances.

Today, these historical figures continue to inspire discussions about gender equality and empowerment in modern China. Their struggles and triumphs highlight both the resilience of women throughout history and the ongoing challenges they face in achieving full equality.

Final Thoughts

The stories of powerful women in ancient China offer a compelling narrative of resilience, intelligence, and determination. Figures like Wu Zetian, Empress Dowager Cixi, Lady Hao, and Ban Zhao defied societal norms to leave lasting impacts on Chinese history. Their achievements spanned military leadership, governance, diplomacy, and cultural contributions, challenging traditional gender roles and inspiring future generations.

These women faced immense challenges in a patriarchal society, yet they managed to wield significant influence. Their legacies continue to resonate today, serving as role models for women around the world who seek to break barriers and challenge existing power structures.

The lessons from their lives are multifaceted. They demonstrate that even within restrictive systems, individuals can challenge norms and create lasting change. Their stories highlight the importance of education, strategic thinking, and leadership—qualities that remain essential for women’s empowerment today.

As we reflect on these historical figures, we are reminded of the ongoing struggle for gender equality. Their achievements underscore the potential for women to shape history and inspire future generations to pursue their aspirations, no matter how daunting the obstacles may seem.

In conclusion, the powerful women of ancient China remind us that history is not just a series of events but a tapestry woven by individuals who dared to challenge the status quo. Their stories continue to inspire, educate, and motivate us to strive for a more inclusive and equitable world.

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook