The story of women in ancient China is one of resilience, duty, and quiet strength. Behind the grandeur of emperors, scholars, and warriors stood generations of women whose roles were deeply woven into the fabric of society. Though often confined by tradition, they shaped families, influenced politics from behind the scenes, and left their mark on history in ways that are often overlooked.

Throughout China’s long history, a woman’s status was largely determined by her family, social class, and the prevailing philosophy of the time. In early societies, women enjoyed more autonomy, with some even wielding political and military power.

However, as Confucian ideals took root, strict expectations for female behavior emerged, emphasizing obedience, virtue, and domesticity. The roles of women varied across different dynasties, reflecting changes in governance, economic conditions, and cultural shifts.

Confucianism played a defining role in shaping gender roles. The doctrine of the Three Obediences and Four Virtues (三從四德)dictated that a woman must obey her father before marriage, her husband after marriage, and her son in widowhood.

Moral expectations reinforced the idea that a woman’s greatest duty was to her family, placing emphasis on chastity, diligence, and silence. Meanwhile, legal codes and social customs reinforced these norms, making it difficult for women to break free from their prescribed roles.

Despite these constraints, women found ways to exert influence. Some became scholars, poets, and strategists, using their intellect to navigate societal restrictions. Others played crucial roles in economic activities, particularly in agriculture, textile production, and trade. In royal courts, consorts and empresses shaped policies and wielded significant power behind the throne.

Studying women’s history across dynasties is essential for understanding China’s broader cultural and social evolution. Each era brought shifts in gender expectations, from the relative freedoms of the Tang Dynasty to the rigid restrictions of the Qing Dynasty. By exploring the lives of women across these periods, we gain deeper insight into not only their struggles but also their resilience and contributions to shaping Chinese civilization.

Let’s now travel back to the Shang Dynasty, where early traces of female power and influence first emerged.

Women in the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE): Power, Religion, and Legacy

The Shang Dynasty, one of China’s earliest recorded civilizations, was a time when women held more influence than in later dynasties. Unlike the rigid patriarchal structures that would come to dominate Chinese society, Shang culture had strong matrilineal roots, meaning family lineage and inheritance were often traced through the mother’s side. Women of noble birth could wield authority, manage household affairs, and even participate in state rituals.

This period saw powerful female figures who played significant roles in governance, warfare, and religious ceremonies. While men were typically the rulers, royal women—especially queens and consorts—held substantial sway behind the throne. They influenced political decisions and maintained strong ties between ruling families through strategic marriages.

The Role of Royal Women in Politics and Religion

One of the most remarkable examples of female power in the Shang Dynasty is Fu Hao (妇好), a queen, military leader, and high priestess. As the wife of King Wu Ding, Fu Hao commanded armies in battle, led diplomatic missions, and performed religious rites—an extraordinary level of authority for a woman in ancient China. Archaeological discoveries of her tomb revealed bronze weapons, jade ornaments, and thousands of oracle bones, proving her significant military and spiritual role.

Royal women also held influence through ancestral worship and divination, both of which were central to Shang society. As intermediaries between the mortal world and the spirits of ancestors, they conducted elaborate rituals to seek guidance from the gods. The Shang believed that maintaining harmony with the spirit world was essential for prosperity, and women played an active part in these ceremonies.

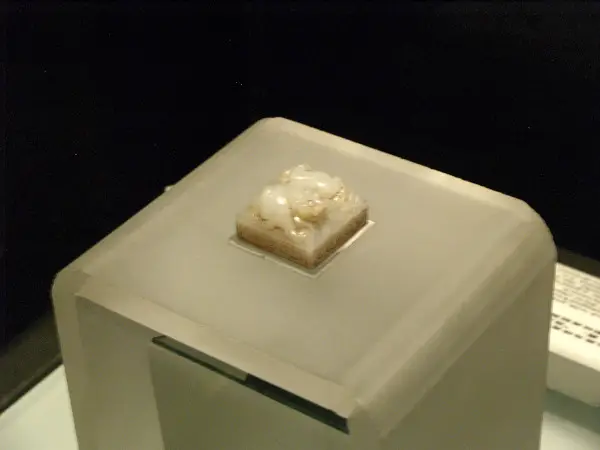

Oracle Bones: Insights into Women’s Lives and Duties

Oracle bones—inscribed pieces of turtle shells or animal bones—provide some of the earliest written records of Chinese history. These bones, used for divination, contain references to the daily lives and responsibilities of women in the Shang Dynasty. Inscriptions mention royal consorts, priestesses, and even female warriors, demonstrating that women were not just confined to domestic roles but also participated in state affairs.

For common women, however, life was vastly different. While noblewomen had the privilege of wielding influence, lower-class women were primarily engaged in agriculture, textile production, and household labor. Many worked in silk weaving, a craft that would later become a cornerstone of China’s economy. Their lives were demanding, but their contributions were crucial to sustaining Shang society.

The Shang Dynasty stands out as a rare period in ancient China where noblewomen could hold military, religious, and political authority. But as history progressed, these freedoms would gradually erode under the influence of Confucian ideals. With the fall of the Shang and the rise of the Zhou Dynasty, women’s roles began to shift—setting the stage for centuries of changing gender norms.

Women in the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE): The Rise of Confucian Gender Norms

The Zhou Dynasty marked a turning point for women in Chinese society. While the Shang Dynasty had allowed noblewomen some degree of power, the Zhou era saw the rise of Confucianism, a philosophy that deeply shaped gender roles for centuries to come. Confucius (551–479 BCE) emphasized a structured, hierarchical society, where harmony was maintained through clear relationships—especially within the family.

For women, this meant increased subordination. The Three Obediences and Four Virtues became the guiding principles of female behavior: a woman was expected to obey her father before marriage, her husband after marriage, and her son in widowhood. Virtue, humility, and domestic skill were valued above all else, limiting women’s opportunities for independence and authority.

However, Confucianism also reinforced the importance of family and education. While women were expected to remain in the domestic sphere, they played essential roles in upholding moral values and raising sons who would become scholars and officials.

Wives, Concubines, and the Structure of the Family

The Zhou Dynasty solidified the patriarchal family system, where men held absolute authority over their households. A man’s status was often reflected in the number of wives and concubines he had, as polygamy was common among the elite.

- The primary wife held the highest status in the family and was responsible for managing household affairs, producing a male heir, and upholding family honor.

- Concubines, while socially inferior to wives, could gain favor if they bore sons. However, their position remained precarious, as they were subject to the whims of their husbands and the power of the primary wife.

- Daughters were often viewed as financial burdens, as they would eventually marry into another family and could not continue their own family’s lineage. Many were married off at a young age in arranged unions that benefited their fathers and brothers.

This rigid structure ensured that women’s lives were defined by their relationships with men. Their primary duty was to bear and raise children, ensuring the continuation of the family line.

Women’s Role in Rituals and Ancestral Worship

Despite their limited public roles, women played an essential part in rituals and ancestral worship, which were central to Zhou society. Maintaining the connection between the living and the dead was crucial for ensuring the family’s prosperity, and women, particularly wives and mothers, were responsible for conducting household ceremonies.

They prepared offerings, tended ancestral altars, and taught their children to respect family traditions. In noble families, queens and consorts participated in larger state rituals, though always in a subordinate role to male rulers.

Through these religious duties, women upheld the spiritual and moral foundations of the family, reinforcing their importance within the domestic sphere—even if they were excluded from political power.

The Expectations of an Ideal Woman in Zhou Society

The ideal Zhou woman was one of modesty, obedience, and quiet diligence. She was expected to remain devoted to her husband, maintain household harmony, and never seek attention or power. Historical texts, such as the Book of Rites (Liji – 禮記 )1, outlined strict behavioral expectations for women, emphasizing humility and service to others.

However, there were exceptions. Some noblewomen, particularly those related to influential families, managed estates, advised their husbands, and even acted as regents in times of crisis. Still, these cases were rare, and the overarching trend was one of declining female autonomy.

The Zhou Dynasty’s emphasis on Confucian values set the stage for thousands of years of gender norms in China. Women became increasingly confined to the household, their roles defined by duty rather than ambition. As the dynasty fell and China entered the turbulent Warring States period, the rigid family structure persisted, reinforcing the idea that a woman’s place was in service to her family.

Women in the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE): Oppression Under Legalist Rule

The Qin Dynasty, though short-lived, brought dramatic changes to Chinese society. Founded by Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, the dynasty was built on Legalist principles—a strict, authoritarian philosophy that prioritized state control, centralized power, and rigid laws over traditional Confucian values.

For women, this meant a further decline in status. Unlike Confucianism, which at least acknowledged the moral influence of women within the household, Legalism saw women as tools for maintaining social order and stability. The state demanded absolute obedience from all subjects, and this extended to gender roles. Women were expected to serve their husbands, produce children—particularly sons for labor and military service—and remain silent and submissive.

Legalist policies also stripped noblewomen of much of their previous influence. Whereas women of the Shang and Zhou dynasties could wield power behind the scenes in royal courts, the Qin government eliminated regional feudal lords and consolidated power under the emperor. This left noblewomen with little opportunity for political maneuvering, as family ties became less significant in the rigid bureaucratic structure.

The Decline of Noblewomen’s Political Influence

Before the Qin Dynasty, noblewomen often held considerable power as consorts, advisors, or even military leaders. However, Qin Shi Huang’s centralization efforts significantly reduced their influence. He weakened aristocratic families by replacing feudal states with direct rule under appointed officials, ensuring loyalty only to the emperor.

In this system, royal women lost much of their previous political leverage. Empresses and consorts were largely sidelined, their roles confined to producing heirs and performing ceremonial duties. Unlike in the Han and Tang Dynasties, where imperial women occasionally held real political power, Qin noblewomen had little opportunity to shape policy.

Additionally, the Legalist focus on practicality and efficiency meant that women’s education was not prioritized. While noblewomen of previous dynasties had access to learning in poetry, philosophy, and governance, the Qin era largely dismissed female literacy, viewing it as unnecessary for their limited roles in society.

The Burdens of Peasant Women Under Strict Rule

For peasant women, life under the Qin Dynasty was especially harsh. The empire’s vast infrastructure projects, including the Great Wall of China and extensive road systems, required enormous amounts of labor. While men were conscripted into military service and forced labor, women were left to manage farms, care for children, and fulfill heavy tax quotas, often under extreme hardship.

Harsh Legalist laws meant that punishments were severe, even for minor infractions. If a woman failed to meet her household’s production requirements or broke any law—even unintentionally—she could face brutal penalties, including corporal punishment or enslavement. Unlike in previous dynasties, where some women could rise in status through family connections, under the Qin, social mobility was nearly impossible.

Despite these difficulties, women remained central to the empire’s economy. They worked in textile production, agriculture, and domestic industries, ensuring the survival of their families even as the government demanded increasingly harsh labor and taxation.

The Legacy of Women in the Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty set a precedent for strict control over women’s lives, reinforcing their subordinate position in both noble and common households. While it unified China and laid the groundwork for future dynasties, it also left little room for female agency. However, with the fall of the Qin and the rise of the Han Dynasty, Confucian ideals would return—bringing both new restrictions and new opportunities for women in Chinese society.

Related reading: Exploring The Importance Of Family In Chinese Culture – Opens in new tab

Women in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE): The Rise of Confucian Womanhood

The Han Dynasty, a period of great prosperity and expansion, saw Confucianism solidify its position as the dominant ideology in China.

This had a profound and lasting impact on the lives of women, shaping their roles and expectations for centuries to come.

Ban Zhao’s Lessons for Women: A Lasting Influence

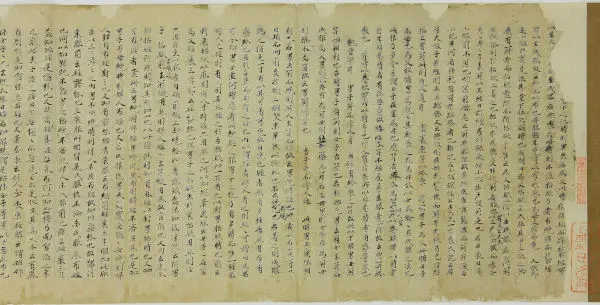

One of the most influential texts on women’s roles in Chinese history emerged during the Han Dynasty: Ban Zhao’s Lessons for Women (Nü Jie). Ban Zhao, a scholar and historian, was one of the most respected women of her time. Her work became a foundational text for female education, shaping gender expectations for centuries.

In Lessons for Women, Ban Zhao emphasized humility, obedience, and devotion as the ideal qualities of a woman. She advised women to accept their subordinate role but also encouraged them to pursue education—not to challenge men, but to better serve their families. While her teachings reinforced patriarchal norms, they also acknowledged the intelligence and moral influence of women in the household.

Her text was widely used in female education throughout imperial China, cementing the Confucian ideals that would define women’s roles for generations.

The Confucian “Three Obediences and Four Virtues”

The Han Dynasty firmly established Confucianism as the guiding philosophy of Chinese society, and with it, the “Three Obediences and Four Virtues” (San Cong Si De) became the standard for women’s behavior:

- Three Obediences:

- Obey her father before marriage

- Obey her husband after marriage

- Obey her son in widowhood

- Four Virtues:

- Morality (de, 德)

- Proper speech (yan, 言)

- Modest appearance (rong, 容)

- Diligent work (gong, 功)

These principles confined women to the domestic sphere, where their primary duties were to bear children, manage the household, and maintain family honor. While noblewomen sometimes wielded influence, the expectation for most women was submission and service.

Women’s Roles in Education and Literature

Despite Confucian restrictions, the Han Dynasty saw an increase in literacy and education for upper-class women. Elite families recognized that an educated woman could better fulfill her role in managing the household, raising virtuous sons, and preserving family traditions.

Ban Zhao herself was a product of this environment. She became a court historian, completing her brother’s historical work, the Book of Han (Han Shu). Other aristocratic women also engaged in literature, poetry, and philosophy—though always within the limits of Confucian expectations.

For lower-class women, education was rare. Instead, they were expected to master textile production, farming, and household labor. Literacy was seen as unnecessary unless it contributed to their domestic responsibilities.

Imperial Consorts and Their Power in Court Politics

Although Confucian ideals restricted women’s roles in public life, the Han court was filled with powerful empresses, consorts, and noblewomen who influenced politics behind the scenes.

One of the most prominent examples was Empress Lü Zhi, the wife of Emperor Gaozu (Liu Bang), the founder of the Han Dynasty. After his death, Lü Zhi took control as regent, ruling with ruthless efficiency. She eliminated political rivals and consolidated power, proving that even within a patriarchal system, ambitious women could shape history.

Other imperial consorts also played key roles in court intrigues, succession struggles, and governance. These women, though operating within a male-dominated system, exercised power through their relationships with emperors, sons, and influential officials.

The Legacy of Han Dynasty Women

The Han Dynasty set the foundation for the Confucian expectations of women that would last for centuries. Ban Zhao’s writings, the Three Obediences and Four Virtues, and the political maneuverings of empresses all shaped the complex role of women in Chinese society.

With the fall of the Han Dynasty, China entered a period of fragmentation, but Confucian ideals persisted—setting the stage for the next great era of Chinese civilization.

Women in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE): A Golden Age of Opportunity

The Tang Dynasty is often considered a golden age for women in Chinese history. Unlike earlier dynasties, where Confucian values strictly confined women to domestic roles, Tang society was more open and dynamic, allowing women greater personal freedom, educational opportunities, and even political influence.

This era saw the rise of Empress Wu Zetian, the only woman to ever rule China as an emperor, along with many noblewomen who played key roles in governance, literature, and the arts. Even common women enjoyed more freedom in daily life compared to previous periods, contributing to the economy, social life, and cultural developments.

A Golden Age for Women’s Rights and Freedom

The Tang Dynasty was shaped by a blend of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist influences, which created a more flexible environment for women. Unlike the rigid expectations of earlier dynasties, women in the Tang had greater mobility, could own property, and participate in social activities.

Some notable changes that set Tang women apart included:

- Less restrictive clothing: Unlike later dynasties that emphasized modesty, Tang women often wore loose, flowing robes, sometimes even adopting men’s attire, symbolizing their relative freedom.

- Horseback riding and sports: Aristocratic women engaged in polo, hunting, and archery, activities traditionally reserved for men.

- Greater independence in marriage: While arranged marriages were still common, divorce and remarriage were more accepted than in later periods.

This social openness allowed women—especially those from elite backgrounds—to explore education, the arts, and even political roles.

Empress Wu Zetian: The Only Female Emperor of China

The most remarkable woman of the Tang Dynasty was Wu Zetian (624–705 CE), the only woman in Chinese history to rule as an emperor. She began as a concubine of Emperor Taizong, later became the wife of his successor, Emperor Gaozong, and eventually declared herself Emperor of China, founding her own dynasty—the Zhou Dynasty (690–705 CE)—before the Tang was restored.

Wu Zetian’s reign was highly controversial but also marked by significant achievements:

- She reformed the government, promoting capable officials based on merit rather than aristocratic birth.

- She expanded the empire’s influence, strengthening diplomatic ties with Central Asia.

- She championed Buddhism, supporting the religion’s growth while also using it to legitimize her rule.

Despite her strong leadership, later Confucian historians painted her as a ruthless ruler who disrupted traditional gender roles. However, her legacy remains one of intelligence, political skill, and unprecedented female power.

The Influence of Noblewomen in Arts, Poetry, and Governance

Beyond Wu Zetian, many Tang noblewomen played active roles in politics, literature, and cultural life. Women from aristocratic families were often well-educated, composing poetry, music, and calligraphy.

One of the most famous female poets of the era was Xue Tao, who was highly respected for her literary talent and became a recognized figure in court culture. Women participated in literary salons, wrote poetry, and exchanged intellectual ideas with men—an unusual level of engagement compared to earlier and later periods.

Additionally, noblewomen often influenced political affairs behind the scenes. As empresses, consorts, or mothers of emperors, they acted as advisors, regents, and patrons of the arts.

Common Women: Work, Family, and Societal Roles

While noblewomen enjoyed education and political influence, common women also experienced a level of freedom that was rare in Chinese history.

- Economic Contributions: Many women worked in trade, textile production, farming, and household industries. Unlike later dynasties that kept women strictly at home, Tang women were often seen running shops, inns, and small businesses.

- Family Life: While patriarchal norms still existed, women had more agency in marriage. Divorce and remarriage were relatively common and socially accepted, especially compared to later periods.

- Social Activities: Women actively participated in festivals, religious ceremonies, and entertainment, contributing to the cultural vibrancy of Tang China.

The Legacy of Women in the Tang Dynasty

The Tang Dynasty stands out as one of the most progressive periods for women in Chinese history. While still living in a patriarchal society, women had greater freedom in movement, marriage, and expression. Wu Zetian proved that a woman could rule a vast empire, while noblewomen contributed to the flourishing arts and culture.

However, after the fall of the Tang Dynasty, Confucian ideals regained dominance, and the restrictions on women’s roles increased in later dynasties—especially with the rise of foot-binding and Neo-Confucianism in the Song period.

Women in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE): The Decline of Female Freedom

The Song Dynasty marked a significant shift in women’s status, as society became increasingly governed by Confucian ideals. While the Tang Dynasty had allowed women greater freedom in movement, dress, and social roles, the Song period saw the rise of Neo-Confucianism, which reinforced traditional gender hierarchies and imposed new restrictions on women.

Despite these limitations, women continued to contribute to literature, philosophy, and the economy, particularly in silk production and domestic industries. However, one of the most enduring and damaging legacies of this era was the spread of foot-binding, which became a defining symbol of female subjugation in China.

The Rise of Foot-Binding and Its Impact on Women

Foot-binding, which is believed to have started among elite courtesans during the late Tang Dynasty, became widespread among upper-class women during the Song Dynasty. The practice involved breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls to create the highly prized “lotus feet,” which were no longer than 3-4 inches.

Though foot-binding was not state-mandated, it became a cultural expectation, especially among wealthy families who viewed tiny feet as a sign of beauty, status, and obedience. The effects of foot-binding were devastating:

- Women with bound feet could not walk properly, limiting their mobility and confining them to domestic spaces.

- The practice reinforced female dependence on male family members, as it prevented women from working in labor-intensive jobs.

- It became a prerequisite for marriage, as families believed bound feet symbolized a woman’s virtue and refinement.

Over time, foot-binding spread to the middle class, and even poorer families began adopting it in hopes of securing advantageous marriages for their daughters. While some lower-class women remained unbound to work in fields or labor-intensive industries, the ideal of the immobile, delicate woman dominated elite and urban culture.

Related reading: The Most Powerful Women in Ancient China – Opens in new tab

Neo-Confucianism and the Restriction of Female Agency

The rise of Neo-Confucianism, a revival of Confucian thought emphasizing strict social order, further restricted women’s roles in Song society. Neo-Confucian scholars, such as Zhu Xi, reinforced the “Three Obediences and Four Virtues”, which demanded absolute submission from women.

Women were expected to be:

- Chaste and loyal to their husbands.

- Obedient to male authority at all stages of life.

- Dedicated to household duties and child-rearing.

Unlike in previous dynasties, where some noblewomen could exert political influence, Song-era women had almost no role in governance. The emphasis on seclusion and domesticity meant that even well-educated women were discouraged from engaging in public affairs.

Widows, in particular, faced extreme pressure not to remarry. The ideal woman was one who remained loyal to her deceased husband, even at the cost of lifelong hardship. Over time, widow chastity became a celebrated virtue, leading to the practice of some widows committing suicide rather than remarrying.

Women’s Roles in Silk Production and Household Economy

Despite their confinement to domestic spaces, women played a vital role in the economy, particularly in the textile industry. The Song Dynasty saw major advancements in silk production, and women were the primary labor force in weaving, embroidery, and fabric dyeing.

In rural areas, women contributed to:

- Sericulture (silk farming), raising silkworms and extracting silk threads.

- Weaving and spinning textiles, which became a major source of income for many families.

- Running household businesses, such as managing shops or engaging in small-scale trade.

Although their work was critical to the economy, women’s labor was largely unrecognized, as Confucian values prioritized men’s contributions over women’s. Women were expected to be industrious in the household, but their contributions were not seen as equal to men’s work in government, scholarship, or military service.

The Influence of Educated Women in Literature and Philosophy

While Neo-Confucianism discouraged women from seeking education, some elite women defied these expectations and made notable contributions to literature and philosophy. Women from aristocratic backgrounds often received private education in poetry, calligraphy, and moral philosophy, though their intellectual pursuits were limited compared to men.

One of the most famous female writers of the Song Dynasty was Li Qingzhao 李清照; (1084–1155 CE), a poet known for her elegant and deeply emotional verses. She wrote about:

- Love and loss, particularly after the death of her husband.

- The turmoil of war, as the Song Dynasty faced invasions from the Jurchens.

- The struggles of women, reflecting on the limitations imposed on female intellectuals.

Li Qingzhao’s work was remarkable because she expressed personal emotions and experiences, something rarely seen in earlier Chinese poetry. However, her life also reflected the difficulties faced by educated women—after her husband’s death, she struggled to maintain her independence, facing legal and societal obstacles.

Though few women had the opportunity to become poets or scholars, those who did often wrote about female struggles, family life, and personal hardships, offering rare insights into the realities of womanhood during the Song period.

The Legacy of Women in the Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was a turning point for women in China—but not for the better. The spread of foot-binding, the dominance of Neo-Confucian ideals, and the increasing restriction of female mobility created a rigid, patriarchal society that would shape Chinese gender norms for centuries.

While women continued to contribute to literature, philosophy, and the economy, their roles became increasingly confined to the domestic sphere. The freedom of Tang women was replaced by a stricter, more repressive order, setting the stage for even harsher restrictions in later dynasties.

Related reading: How Chinese Family Values Shape Personal Development – Opens in new tab

Women in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE): A Period of Contrasts

The Yuan Dynasty, established by the Mongols, brought dramatic cultural shifts to China, including changes in the status and roles of women. Unlike the preceding Song Dynasty, which confined women under Neo-Confucian ideals, the Mongol rulers introduced more flexible gender norms, particularly among the upper classes.

However, these changes did not lead to a complete transformation of women’s lives. While noblewomen enjoyed greater freedom and influence, peasant women continued to face harsh labor and social constraints. Women also became key participants in trade and business, as the Mongols encouraged commerce and economic expansion.

Mongol Customs and Their Effect on Chinese Women

The Mongols had a more egalitarian view of gender roles compared to the Han Chinese, particularly in their nomadic traditions. Mongol women:

- Rode horses and participated in hunting and archery, activities largely denied to Han women.

- Managed family affairs, including economic and political decisions, when men were away at war.

- Had greater mobility and fewer restrictions on public participation.

When the Mongols established the Yuan Dynasty, some of these customs influenced elite Chinese women. Compared to the highly secluded Song women, Yuan noblewomen had:

- More opportunities to travel and engage in politics.

- Less emphasis on foot-binding, as Mongols did not practice it.

- A greater role in business, managing estates and overseeing trade.

However, these freedoms were largely limited to the upper classes. Mongol customs did not completely erase Confucian gender norms, and most Han Chinese women remained under traditional patriarchal structures.

Women’s Roles in Trade and Business Under Yuan Rule

One of the biggest changes under Mongol rule was the economic expansion, particularly in trade. The Yuan Dynasty actively promoted commerce, banking, and international exchanges, allowing women to participate in ways that had been discouraged in earlier dynasties.

Key economic roles of women during the Yuan Dynasty:

- Merchant women ran shops, inns, and textile businesses.

- Women in urban centers worked as weavers, silk producers, and artisans.

- Mongol noblewomen controlled large estates, overseeing agricultural production and livestock.

Some Chinese women even gained influence in money lending and financial management, as trade networks connected China with Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. The Silk Road flourished under Mongol rule, and women, particularly in wealthy merchant families, played roles in overseeing trade transactions.

Despite these economic opportunities, peasant women in rural areas saw little change. They remained tied to agricultural labor, household duties, and local markets, continuing the cycle of hardship and low social status.

The Contrasting Lives of Noblewomen and Peasant Women

The Yuan Dynasty highlighted a stark divide between elite and lower-class women.

Noblewomen:

Mongol noblewomen, in particular, enjoyed high status and influence. Some even held political power, acting as regents or advisors while their husbands or sons ruled. Unlike their Han Chinese counterparts, Mongol elite women were not confined to private quarters and could participate in court affairs.

Notable examples include:

- Empress Chabi, the influential wife of Kublai Khan, who promoted Buddhism and diplomatic relations with the Song Chinese.

- Princesses and noblewomen who held land, commanded armies, and played active roles in governance.

Han Chinese noblewomen under Mongol rule also benefited from this loosening of restrictions. Though they still adhered to Confucian ideals, they had more mobility, economic influence, and personal freedom than during the Song period.

Peasant Women:

For peasant women, life remained harsh and labor-intensive. They worked in:

- Farming, harvesting crops, and raising livestock.

- Domestic labor, serving wealthier families.

- Textile production, spinning silk and weaving cloth for trade.

Many peasant women never experienced the increased freedoms of Mongol noblewomen. Instead, they continued to face poverty, social constraints, and limited rights.

The Legacy of Yuan Dynasty Women

The Yuan Dynasty was a time of contrasts for women. While Mongol customs allowed noblewomen more freedom and influence, peasant women remained in traditional, labor-heavy roles.

Although the Mongol rulers did not enforce Confucian restrictions as strictly as previous dynasties, their rule was relatively short-lived. When the Ming Dynasty overthrew the Yuan, many of the Confucian ideals of female obedience and seclusion returned, leading to greater restrictions on women in the following era.

Related reading:More Than Just a Wedding: Unveiling the Cultural Significance of Chinese Marriage Customs – opens in new tab

Women in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE): A Return to Tradition

The Ming Dynasty marked a period of significant social and cultural change, especially for women. After the relatively more open social structure of the Yuan Dynasty, the Ming period saw the reinforcement of Confucian norms that prioritized female seclusion, obedience, and chastity. These values were especially enforced by the state and elite families, leading to greater limitations on women’s roles in both public and private spheres.

However, despite these increasing restrictions, women continued to contribute to literature, domestic industries, and family businesses—often behind the scenes. Some even managed to leave lasting legacies in the world of poetry and cultural thought, though their lives were often confined to the roles prescribed by Confucian teachings.

Increased Restrictions and the Reinforcement of Confucian Norms

The Ming Dynasty represented the height of Confucian influence in Chinese society. Under the Ming emperors, Confucian ideals of patriarchy and female virtue were rigorously applied to women’s lives. Women were expected to be obedient daughters, faithful wives, and devoted mothers, and their social roles were largely confined to the home and family life.

Key features of this increased restriction included:

- Strict moral codes that dictated women’s behavior in public and private.

- The exclusion of women from education and intellectual circles, though some elite women still had access to private tutors.

- Foot-binding became even more prevalent among elite women as a symbol of beauty, femininity, and subservience, leading to physical and social constraints for women of all social classes.

The reinforcement of these Confucian norms also resulted in a heightened sense of family duty, where women’s primary responsibility was maintaining the integrity and harmony of the household.

The Rise of Widow Chastity and Female Virtue Movements

One of the most striking aspects of the Ming era was the rise of the widow chastity movement, which encouraged women to remain chaste after the death of their husbands. This movement was supported by Confucian scholars, who believed that widows should demonstrate moral fortitude by avoiding remarriage and remaining faithful to their deceased husbands.

In many ways, this movement reinforced women’s subordinate status in the family. A widow was often seen as the embodiment of virtue, and her actions were meant to uphold the honor and integrity of her husband’s family. As a result, widows were expected to:

- Avoid remarriage, even if it meant living in poverty or solitude.

- Devote themselves to their children, often at the expense of their personal desires.

- Engage in pious acts and show unwavering loyalty to their late husbands.

This period saw the publication of guides and treatises on widowhood and female chastity, encouraging women to uphold their moral duty above all else. Some women, particularly in the elite classes, became famous for their chastity and virtue, and they were often celebrated in literature and popular culture. However, this also created immense social pressure for women to comply with these expectations.

Women’s Involvement in Domestic Industries and Literature

Despite the strictures of Confucian society, women in the Ming Dynasty continued to play important roles in various aspects of domestic production and literature, albeit often in the background.

Domestic Industries and Household Economy

While women were excluded from political life, they remained central to the household economy. In rural areas, women were responsible for agricultural labor, working the fields, tending livestock, and performing essential domestic tasks. In urban settings, women were involved in:

- Silk production: Weaving, embroidery, and other textile-related work remained important industries for women.

- Pottery and ceramic work, with women contributing to the production of both practical and decorative items.

- Tea production, where women were key players in the cultivation and preparation of tea.

Although their work was essential to maintaining the household and contributing to the economy, women’s roles in industry were often unrecognized or overshadowed by the contributions of men.

Literature and the Arts

In terms of literature, the Ming Dynasty saw a flourishing of Chinese drama, poetry, and literature, with some women making notable contributions to the arts. Although women were still largely excluded from public intellectual circles, many aristocratic women were taught to read and write and some even became well-known poets.

One of the most famous women writers of the period was Xue Susu, who was celebrated for her poetry and literary contributions. Despite the increasing pressure on women to remain confined to domestic life, she and other women like her found ways to express their thoughts and leave their mark on Chinese culture.

Additionally, some women were also involved in the production of art, with calligraphy and painting being areas where educated women could gain recognition. However, their works were often attributed to male relatives or their accomplishments were undervalued by a male-dominated society.

The Legacy of Women in the Ming Dynasty

The Ming Dynasty was a period of contradictions for women. On one hand, Confucian values emphasized women’s subordination and restricted their freedom, pushing them into more domestic roles. On the other hand, some women found ways to contribute to literature, domestic industries, and even social movements advocating for female virtue.

Though they were largely confined to the private sphere, women still managed to preserve cultural traditions and maintain economic stability for their families. However, the legacy of the widow chastity movement and foot-binding would go on to define women’s experiences in China for centuries to come.

Women in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE): The Peak of Confucian Restrictions and the Beginning of Change

The Qing Dynasty, China’s last imperial dynasty, marked the strictest period for women under Confucian rule. While the dynasty itself brought economic prosperity and territorial expansion, it also reinforced traditional gender roles, with women’s lives remaining tightly constrained by Confucian morality and the patriarchal structure of society. However, even during this period of intense restriction, women began to participate in rebellions, social movements, and the first educational reforms that would eventually lead to changes in their roles.

The Strictest Period for Women Under Confucian Rule

Under the Qing emperors, the Confucian ideal of women’s obedience, seclusion, and domesticity was most rigorously applied. Women’s roles were predominantly defined by the family structure, where they were expected to be dutiful daughters, wives, and mothers. Key elements of their lives during this time included:

- Increased confinement: Women’s lives were further confined to the inner quarters of the home (the “harem”), where they were expected to manage domestic affairs and raise children while maintaining a low public profile.

- **Emphasis on obedience and chastity: Confucian teachings regarding the “Three Obediences and Four Virtues” were strictly enforced, emphasizing women’s duties to their fathers, husbands, and sons, with little room for independence or personal desires.

- Submissive behavior was not just culturally encouraged but expected as part of a woman’s moral virtue.

This period saw the reinforcement of foot-binding, which had become a significant cultural symbol by the early Qing period, especially among the elite, and served to further restrict women’s mobility and independence.

The Decline of Foot-binding Among Lower-Class Women

While foot-binding remained widespread among the upper classes during the Qing Dynasty, it began to decline among lower-class women as societal and economic changes took place. Several factors contributed to this gradual shift:

- Economic pressures: Many lower-class families could not afford the labor needed to bind a daughter’s feet, as it required long-term care and often hampered a woman’s ability to engage in physical work.

- Practicality: Peasant women, who needed to work the fields, could not afford the inconvenience of bound feet, which made farming and manual labor much more difficult.

- Resistance to the practice: Over time, reform movements and growing awareness began to spread, particularly among intellectual circles. Some criticized foot-binding as an oppressive tradition that limited women’s potential and freedom.

Despite these shifts in lower-class society, foot-binding remained deeply entrenched among the elite, where it was viewed as a sign of beauty, status, and femininity. It continued to symbolize a woman’s moral purity and family honor.

Women’s Participation in Rebellions and Social Movements

The Qing Dynasty witnessed significant social unrest and rebellions, and, though women’s participation was often overlooked or underappreciated, they played important roles in various uprisings:

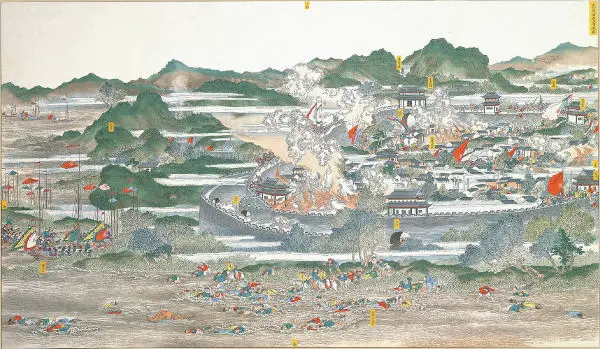

- The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864): One of the largest uprisings in history, the Taiping Rebellion saw women participate in military action, including combat and leadership roles. The rebellion’s leader, Hong Xiuquan, claimed to receive divine visions, and women were encouraged to fight alongside men, breaking many traditional gender roles.

- The Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901): Women also participated in the anti-foreign Boxer movement, which called for the expulsion of foreign influence. Many women fought alongside men, often in the guise of martyrs and heroes.

Women’s involvement in these rebellions was revolutionary, as they took on public roles and demonstrated their ability to defy patriarchal norms in times of social and political crisis.

These rebellions and movements were often led by social dissatisfaction rather than an ideological push for gender equality, but they opened the door for the first sparks of female activism, showing that women could contribute significantly to China’s political landscape.

The First Sparks of Change: Education and Reform Efforts

The later Qing period saw the beginnings of change in the status of women, particularly in the areas of education and social reform:

- Educational reforms: During the late Qing, the first schools for girls were established, particularly in urban centers. Western-style education began to spread, and some families began to see the value in educating their daughters in subjects like literature, math, and science. Although these schools were limited and typically focused on the elite, they represented a significant step toward female empowerment.

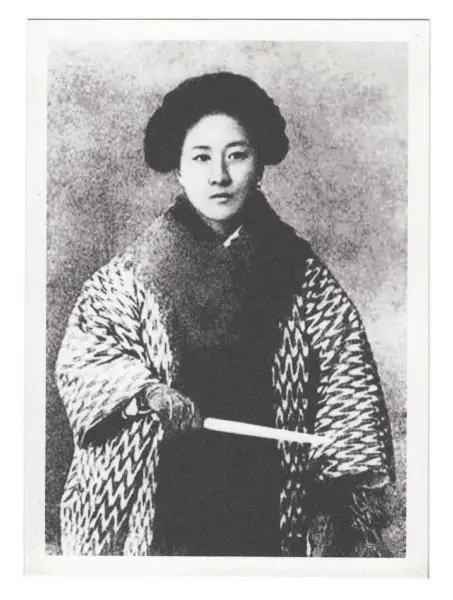

- Women’s rights activists: Intellectuals like Qiu Jin, an influential revolutionary, advocated for women’s education and emancipation. Her works called for the abolition of foot-binding, better access to education, and greater participation of women in public life. She later became involved in anti-Qing revolutionary efforts, and although her impact was cut short by her execution, she inspired future generations of women in China.

- Feminist movements: The rise of feminist thought in the early 20th century also contributed to the growing push for women’s rights. Women in cities like Shanghai and Beijing began to form societies and organizations aimed at promoting social, educational, and legal reforms to benefit women.

While the Qing Dynasty ended in 1912 with the fall of the imperial system, these early movements set the stage for the changes in women’s rights that would unfold in the 20th century, particularly in the Republic of China.

The Legacy of Women in the Qing Dynasty

Though the Qing period is often remembered for its strict Confucian traditions, the experiences of women during this era laid the groundwork for future movements toward gender equality in China. Despite enduring significant social constraints, women began to break down barriers through participation in rebellions, literary contributions, and early educational reforms. While much work remained to be done, the Qing Dynasty was a critical moment in China’s history, as it set the stage for the modern feminist movements that would emerge in the early 20th century.

End Words: A Legacy of Resilience and Transformation

The journey through the role of women in ancient China, across its many dynasties, reveals a complex and often contradictory picture. From the potential matrilineal influences of the Shang Dynasty to the strict Confucian constraints of the Qing, women’s experiences have been shaped by evolving social norms, philosophical systems, and political landscapes. While often confined to the domestic sphere and subject to patriarchal control, women throughout Chinese history have demonstrated remarkable resilience, agency, and influence.

Their contributions, though sometimes overlooked, are woven into the very fabric of Chinese civilization. From the powerful empresses who shaped dynasties to the countless ordinary women who toiled in fields, managed households, and contributed to the family economy, women have played a crucial role in the development of Chinese society. Their involvement in religious rituals, their artistic and literary achievements, and even their participation in rebellions and social movements highlight their strength and determination.

The story of women in ancient China is not simply a narrative of oppression and constraint. It is also a story of adaptation, resistance, and the persistent pursuit of self-expression. It is a story of women who, even within limiting circumstances, found ways to exert influence, make their voices heard, and leave their mark on history. By understanding their experiences, we gain a deeper appreciation of the richness and complexity of Chinese history and a greater understanding of the long and arduous journey towards gender equality. The legacy of these women, their struggles, and their triumphs, continues to resonate today, reminding us of the importance of continuing the fight for justice and equality for all.

Related reading: Meet The Four Great Beauties of Ancient China – Opens in new tab

Referrals to international organizations related to Gender equality and Women’s Rights in modern China.

- “The Book of Rites” (Li ji – 禮記)at the Library of Congress ↩︎

Stay in Touch

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here!

Join our newsletter by using the forms on this website or click here! Follow us on Google News

Follow us on Google News Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Facebook